Catholic Fascists in the NYPD, 1939-1940

The relationship between the police, rightwing militias, and religion goes back decades and has lessons for today

(Image of a “Blue Mass” for the police. Image source: CBP photo by Jaime Rodriguez, Sr.)

In Stone Mountain, Georgia, a hulking police officer in riot gear fist bumps a militia member carrying an assault rifle during a far-right rally. Elsewhere, during a protest against police violence in Kenosha, Wisconsin, a voice from a loudspeaker on an armored police vehicle broadcasts a message to militia members: “We appreciate you guys. We really do.”

These images of police fraternization with right-wing groups in the summer of 2020 brought the intimacy of American law enforcement and militias back to the public’s attention. The massive Black Lives Matter protests of that summer provoked far-right counter demonstrations and armed militia men claiming to assist the police. This relationship is not peculiar to the present day: the overlap between state security forces and irregular countersubversive militias was visible in the Red Summer of 1919 and the U.S. supported-mass killings of leftists and ethnic minorities in Indonesia in 1965.

In the United States, the relationship between the police and the far right has a long history, one that is entangled with the history of Christianity. Catholic churches in east coast cities have conducted Blue Masses, special church services dedicated to the police since the early decades of the 20th century. In recent years, Evangelical outreach to law enforcement has taken the form of police-themed devotional retreats and the publication of police-centric Bibles. These phenomena past and present signal a symbiotic relationship between two institutions that see themselves as guardians of the traditional moral order.

Paranoia over perceived challenges to conservative Christianity’s comingling with the police has given rise to fascist organizing inside and outside of police departments. During the attempted coup on January 6th, 2021, some police officers participated in the insurrection or leaked intelligence to the Proud Boys even as the Capitol Police were left exposed to the crowd’s violence. Throughout the country, police leadership have become aware of neo-Nazi infiltration within their ranks, but it remains incredibly difficult to remove these officers from the force. One persistent factor has been the inability of the police to police itself when it comes to far-right infiltration. The question of whether this is a bug or a feature of law enforcement remains relevant and suggests that looking to earlier contexts could be instructive.

(Image source: Elijah Nouvelage for Reuters)

From the summer of 1939 through February 1940, the New York City Police Department dealt with allegations from local residents and journalists that a Catholic fascist organization, the Christian Front, had broad support among the department’s rank-and-file. The Christian Front and its offshoots subjected Black and Jewish New Yorkers to frequent harassment and violence. Examining journalistic coverage of this phenomenon from New York’s Black and Jewish communities reveals serious concern over the NYPD’s white Catholic identity as fascism was spreading through Europe and into the United States. Given that the NYPD’s personnel was largely Catholic and that a fascist Catholic organization targeted those police for recruitment, how did reporters for Black and Jewish newspapers understand Catholicism’s role in this situation?

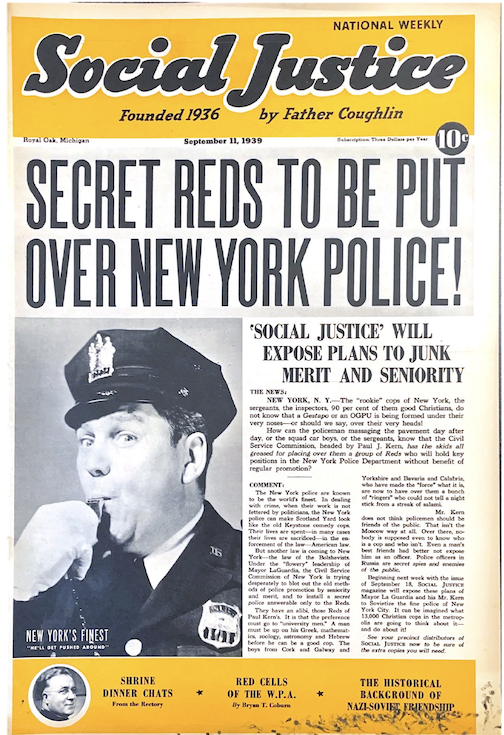

An early warning of the cozy relationship between the police and the Christian Front came in an article by James Wechsler in the July 22, 1939 issue of The Nation titled “The Coughlin Terror.” Wechsler reported on the violent influence of radio celebrity Father Coughlin across New York City. Coughlin, a Catholic priest based out of Royal Oak, Michigan, pushed antisemitic conspiracy theories, pro-Axis propaganda from Germany, Spain, and Italy, and Christian nationalism to millions on the airwaves and in his weekly newspaper, Social Justice. It was in the pages of this weekly that Coughlin’s East Coast emissary, the Brooklyn-based Father Edward Lodge Curran, called for the formation of a “Christian Front” to counter the anti-fascist Popular Front, a temporary alliance between Communists, socialists, and progressive liberals. Coughlin enthusiastically promoted this idea of militant Christians organizing together to use “the Franco way” to oppose “Judeo-Bolshevism.”

Across New York City, Social Justice salespeople harassed and abused Jews and leftists in subway cars, on subway platforms, and at major intersections. The Christian Front and an offshoot, the Christian Mobilizers, held street meetings proclaiming a cosmic battle between the Body of Christ and the Body of Satan. The appearance of these far-right Christian groups prompted condemnation from Jewish and Catholic intellectuals. One group of prominent New Yorkers, including Hubertus zu Loewenstein, Dorothy Parker, and Franz Boas, brought out the magazine Equality to be sold on the street as a direct refutation of Social Justice.

(Front page of Social Justice, September 1939. Image source: University of Detroit Mercy)

This war of words sparked physical violence on the streets and in subways throughout the summer of 1939, and it was at this point that the NYPD became part of the story. In “The Coughlin Terror,” Wechsler quoted anti-Coughlin protestors who said they did not feel protected by the police. Instead, they were told that there were thousands of members of the Christian Front in the police department and that soon they would “resign from the force and…settle the question our way.” Wechsler assured his readers that this was not “a blanket indictment” of the police. Nonetheless, a memo from the American Jewish Committee confirmed widespread police indifference to violence against anti-Coughlin protesters. The situation became urgent and required oversight from Mayor Fiorello La Guardia.

The impact of “The Coughlin Terror” rippled through New York City’s Yiddish presses. Two days later The Forward, the social-democratic Yiddish paper with the largest circulation in the country, adapted and commented on Wechsler’s piece. It was accompanied by an editorial “Duty of the Police—Nothing More,” urging Mayor La Guardia to insure police impartiality and fairness. The Forward’s editors were impatient with La Guardia for his unwillingness to crack down on Christian Front rallies across the city, which the mayor understood to be the free exercise of First Amendment rights. What they could not have known was that since April 1939, La Guardia had directed the NYPD’s Alien Squad to monitor Christian Front meetings. And the NYPD was not the only police agency focusing on the Christian Front; in December 1939, the FBI arrested 18 members of the group in Brooklyn for conspiring to overthrow the government. Two months later, in February of 1940, NYPD Commissioner Valentine ordered the rank and file of the NYPD to fill out a questionnaire to determine whether officers and employees were members of the Communist Party, the pro-Nazi German-American Bund, or the Christian Front. Initial reports from the FBI suggested that over one thousand NYPD personnel belonged to the Christian Front. On February 15th, La Guardia released a statement that the majority of the department had completed the survey. Twenty-seven officers admitted to still being Front members and would have to quit the organization. La Guardia explained that the 407 officers who had been involved with the Front had done so under the mistaken impression that the Front was a religious organization and not a far-right political group. Once the officers realized the extremity of the Christian Front, he said, they quit.

A questionnaire, even with a high response rate, hardly qualified as a thorough internal investigation. The Yiddish press was not impressed. Hundreds of police officers had admitted to membership, after all. The Anarchist Fraye Arbayter Shtime [Free Voice of Labor] lamented the missed opportunity to “clean out” the right-wing “infestation” of the police. They believed this left the department as a “toy [shpilzeyg] in the hands of fascist bandits.” The situation meant that “decent people” [onshtendike menshn] would be obliged to organize their own self-defense since they could not rely on the police.

Perhaps the most intense example of improvised Jewish self-defense came in Newark, New Jersey, where the Christian Front and the German-American Bund were thriving. Local crime boss Abner “Longie” Zwillmann had recruited boxer Nat Arno in 1933 to organize a Jewish self-defense paramilitary, the Minutemen. Most likely these were not the “decent people” who the Yiddish paper had in mind, but the Minutemen battled fascists and faced off against police in their effort to discourage antisemitic political groups from expanding their foothold in Newark.

Refusing to be put on the defensive over the Christian Front’s relationship with the police department, Social Justice counter-attacked with a conspiracy theory of Communists taking over the NYPD. “The Christian stalwarts” and “blue coated warriors” in the NYPD were not at fault, but instead Mayor La Guardia and his head of the Civil Services Commission, Paul Kern. Kern had instituted a policy of awarding merit points for officers earning college credits. Robert Moses was Kern’s fierce rival and leaked information about the merit program. Social Justice ran with the story, reporting that Kern was establishing a secret police force patterned after the Soviet OGPU, disempowering the “boys from Cork and Galway and Yorkshire and Bavaria and Calabria” in favor of students from City College of New York, an institution known for its Jewish student body and left-wing politics.

New York City’s Black newspapers refuted the conspiracy theory. The New York Age reported on September 30, 1939 that Coughlin’s assertion that Communists were taking over the NYPD was “a campaign…aimed at barring Negroes and Jews from the New York City Police Department.” What’s striking about this statement is that Social Justice nowhere directly includes references to Black police recruits; its racial animus is explicitly directed against hypothetical Jewish recruits. And yet it is clear that the good Christians of the NYPD, according to Social Justice, were whites with European ancestry. This is not to say that Social Justice did not promote anti-Black racism in other stories it published, but it was not directly at the center of this one.

Claims that Kern’s program endangered Christian white ethnic domination of the NYPD were grossly exaggerated. Of the last round of candidates who qualified for the civil service in 1939, one third were Jews and five percent were African Americans. La Guardia’s reforms attempted to integrate the NYPD, but the results left Black police officers clustered in Black neighborhoods without any chance for promotion, preserving the racial hierarchy of the department.

Violence between white Catholics, especially Catholic police officers, and Black New Yorkers was nothing new, going back to the Battle of San Juan Hill in 1905, and provoked more recent unrest such as in Harlem on March 19, 1935. But the Christian Front was a new phenomenon. The New York Age reported attacks on Black youth in Washington Heights and called for a stronger Black police presence in August of 1939, even if the editors were normally against the segregation of Black police. Throughout the summer of 1939, the Black Communist Crusader Press Agency reporter Eugene Gordon counted at least five “Coughlinite” assaults on Black New Yorkers around Riverside Drive.

By and large, the stance of both Black and Jewish newspapers was that Coughlin and the Christian Front were not authentic representatives of Catholicism. In his column for the Amsterdam News, W.E.B Du Bois referred to Coughlin’s paramilitaries as “The Un-Christian Front.” Black papers mounted sharp criticism of the Catholic Church’s failures in opposing Jim Crow, lynching, and racial segregation in New York City, but they did not treat Coughlin as its legitimate representative.

Yiddish newspapers such as The Forward and the Communist Morgen Frayhayt also sought to marginalize Coughlin’s position in the Catholic Church, pointing out that prominent Catholics such as Cardinal Mundlein of Chicago and theologian John Ryan had denounced the radio priest. That did not mean, however, that they failed to take Coughlin’s power among Catholics seriously. Yiddish papers used the threat of the Christian Front to educate their readers about Catholic history and sociology, continuing the Jewish tradition of producing reliable representations of gentile communities in New York City for the purpose of navigating dangerous terrain.

The most striking example of this is the journalist A. Alterson’s weekly series that ran in the summer of 1939 in the Morgen Frayhayt,“Conversations with Catholic leaders.” Alterson interviewed local priests about Coughlin and the Christian Front. One priest, Father DeMaria, urged Jewish leaders to do more to counter antisemitic propaganda and, in the same conversation, asked Alterson if it were really true that all Jewish girls were sexually promiscuous. When a stunned Alterson asked the priest where he had heard such a thing, DeMaria sheepishly replied that a local police officer had told him. Another priest asserted that while forceful suppression was justified against “Godless Jews, the Bolsheviks,” the rest should be left alone.

Despite witnessing this frank affirmation of violence, Alterson maintained that outreach to Catholic clergy was all the more worthwhile because of the priests’ enormous influence in their parishes. Even more promising were his conversations with progressive Catholic activists, such as the Committee of Catholics to Combat anti-Semitism and the Catholic Worker Movement, who were organizing and publishing against Catholic antisemites locally and nationally. Writing for a radical Jewish audience, Alterson’s point was that many Catholics felt threatened by Coughlin and that Jewish-Catholic solidarity was possible, however unlikely it may have first appeared.

By spring 1940, the NYPD/Christian Front scandal seemed to evaporate, as the Justice Department’s case against the 17 accused Christian Front conspirators fell apart due to prosecutorial incompetence. After the acquittal of the 17 defendants in June 1940 it seemed like the Christian Front was a non-story, or if it were a story, it was about government overreach rather than impending fascist takeover. Indeed, historian Leo Ribuffo coined the term “the Brown Scare” to describe liberals’ exaggeration of the domestic far right’s danger to national security that justified FDR’s empowerment of the FBI to monitor and suppress isolationists in the buildup to the U.S.’s entry into WWII. Initially this targeted the right; after WWII, however, state power would busy itself with the infiltration and destruction of the left.

Eighty years later the specter of fascist conspiracy makes for good edutainment in the wake of the Trump presidency. The popularity of Rachel Maddow’s podcast Ultra, covering Nazi plots and the Christian Front, attests to this. The problem, according to labor historian Nelson Lichtenstein, is that the domestic far right has become far stronger now than it ever was in the 1930s, and it got that way not through conspiracies but by building institutional power in the U.S. government, the kind of power deployed by J. Edgar Hoover in his counter-subversive dragnet.

And yet, the Christian Front’s attempts to recruit, infiltrate, or at least win the sympathy of the NYPD reveal the close proximity of the conspiratorial, street-level, and institutional forms of right-wing power. The Front did not cease to be a problem for the NYPD or for other police forces on the East Coast. During the Brooklyn sedition trial, John F. Cassidy testified that 500 NYPD officers had applied for membership in the Christian Front in Brooklyn alone. In April 1940, the FBI notified the mayor of Newark that 30 members of the Police Department were members of the Front. Mayor Ellenstein took over the Department and demoted and reassigned approximately 50 officers. Meanwhile, Boston’s police department turned a blind eye to intense antisemitic violence throughout the 1940s.

In 1943, the issue of NYPD tolerance of antisemitic violence reappeared as patrolman James Drew was accused of associating with the Christian Mobilizers and possessing seditionist Christian Front literature. Drew was acquitted and even appeared on La Guardia’s weekly radio broadcast, prompting outrage from local Jewish communities who were facing an uptick in street violence and racist graffiti on synagogues, schools, and shops. Despite persistent complaints from residents about antisemitic violence, neither the local police nor the New York Catholic archdiocese was inclined to take the situation seriously. La Guardia ordered the formation of a special division to combat antisemitism in the city after constant pressure from Jewish community members. It was in this same period, in 1944, when the violence reached such a crescendo in Washington Heights that local Catholic priests finally agreed to appear at an interfaith rally to condemn the attacks.

***

Fascist organizing and state violence feed off of each other, in the 1930s and in the present. One contributing factor is that the police are hardly monolithic. In New York some local precincts refused to take a firm hand against Christian-Front aligned street violence, even as another division of the NYPD was surveilling the Christian Front. That division, the “Alien Squad,” then opted not to share the intelligence it gathered with the FBI when the bureau was investigating the Front. The bureaucratic divisions and internal rivalries in U.S. law enforcement played a part in the duration of Christian Front activities. Moreover, the lack of political will to scrutinize the conditions that enabled Christian Front recruitment inside the NYPD left room for subsequent iterations of far-right organizing, such as the John Birch Society, the Law Enforcement Group (L.E.G.), and later, the Oath Keepers.

The story of the Christian Front and the NYPD represents both continuity and rupture in the police’s relationship with the far right. Then, as now, it remains difficult for the police to deal with far-right recruitment in their ranks. Church support for policing remains strong even as the power and influence of institutional Christianity has since waned. This combined with growing critical scrutiny of the police may even contribute to a closer relationship between the leadership of church and state security forces as both understand themselves to be pillars of the traditional moral order. The decline of the Yiddish press, the Black press, and local news in general represents a sharp contrast between the present and the New-Deal-era USA, not to mention an impoverishment of fine-grained local reporting and commentary. All the papers here display some level of ambivalence about policing. The Black papers, The New York Age in particular, wanted to see Black New Yorkers integrate the NYPD to build successful careers and influence city affairs, but they also never stopped reporting on police violence. The Forward urged neutrality and duty on the part of law enforcement while recognizing the weakness of the mayor’s efforts at oversight. Anarchist and Communist papers were more cynical (and arguably realistic) about the tight relationship between far-right groups and the police, but that alone did not entail abolitionism.

The far right’s attitude was somewhat less complicated, despite some rocky moments in its relationship with law enforcement. Social Justice consistently lavished praise on the police, and even after the Brooklyn trial Coughlin expressed sympathy for Hoover and his men, portraying them as the unwilling tools of unscrupulous politicians. The rank-and-file Fronters expressed their resentment of NYPD surveillance during street meetings but even this criticism was tempered by an apparent faith in the beat cops’ sympathy with their cause. The Christian Front recognized the necessity of the police for implementing their vision of an authoritarian, white-supremacist Christian state. Their hopes for swift realization of this project were obviously frustrated. But that goal remains central to far-right ambitions to this day. And sympathetic law enforcement personnel remain in high demand.

Klaus Yoder is a historian of Christianity and a podcaster for Seven Heads, Ten Horns: The History of the Devil. He teaches in the Religion Department at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, NY.