-

-

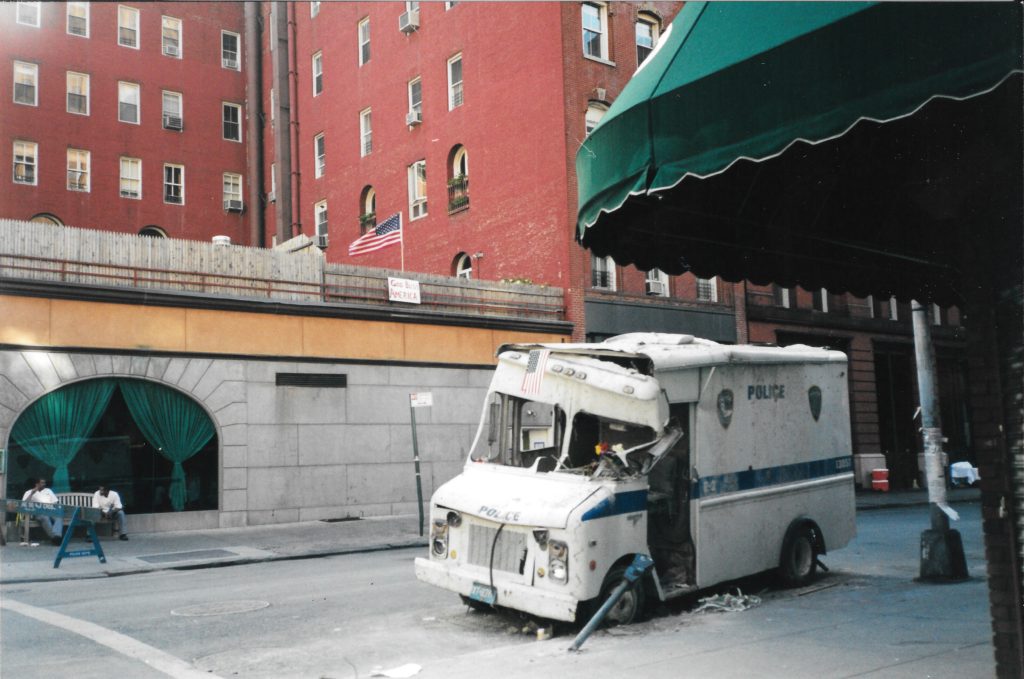

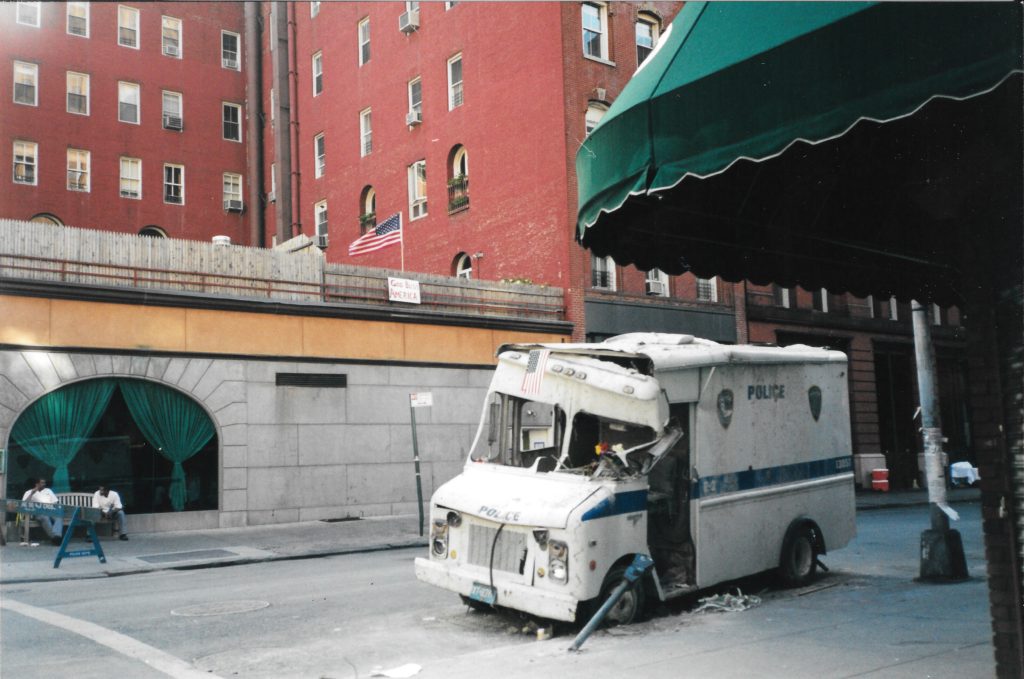

Canal St. and Greene St. 2001

-

-

Canal St. and Greene St. 2016

By Patrick Blanchfield

2001 Photographs by the Blanchfields

2016 Photographs by Evan Simko-Bednarski

In the 9/11 Museum Preview Site and Gift Shop on Vesey Street, artifacts sit alongside souvenirs. A fire hose, bits of rubble, a pair of commemorative motorcycles – these relics are not for sale. The tchotchkes, though, are. Those items are geared towards all consumer demographics: clothing and plateware for adults, toy police cars and plush Service Dogs for kids. Above, projected onto a wall, a video of rebuilding efforts and interviews with survivors from their hospital beds. Playing over everything, the strains of a Philip Glass concerto.

What is remembered, what is forgotten? Which memories do we cling to as anchors, which do we allow to sink, and which surge up from beneath the surface, unbidden and unwanted? And how do we string together those memories into something meaningful?

-

-

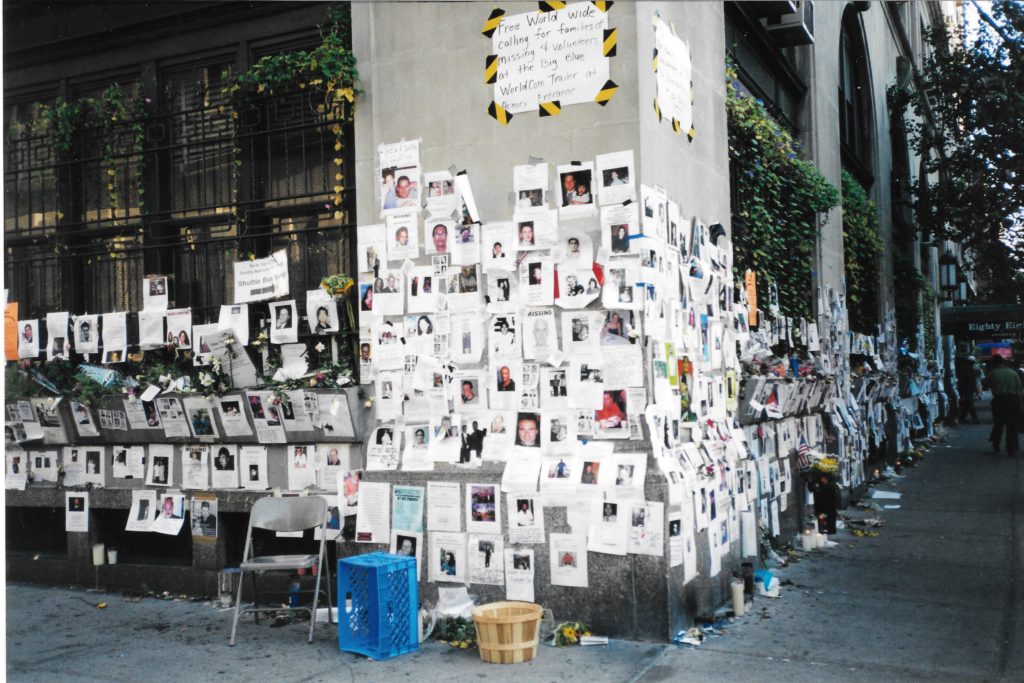

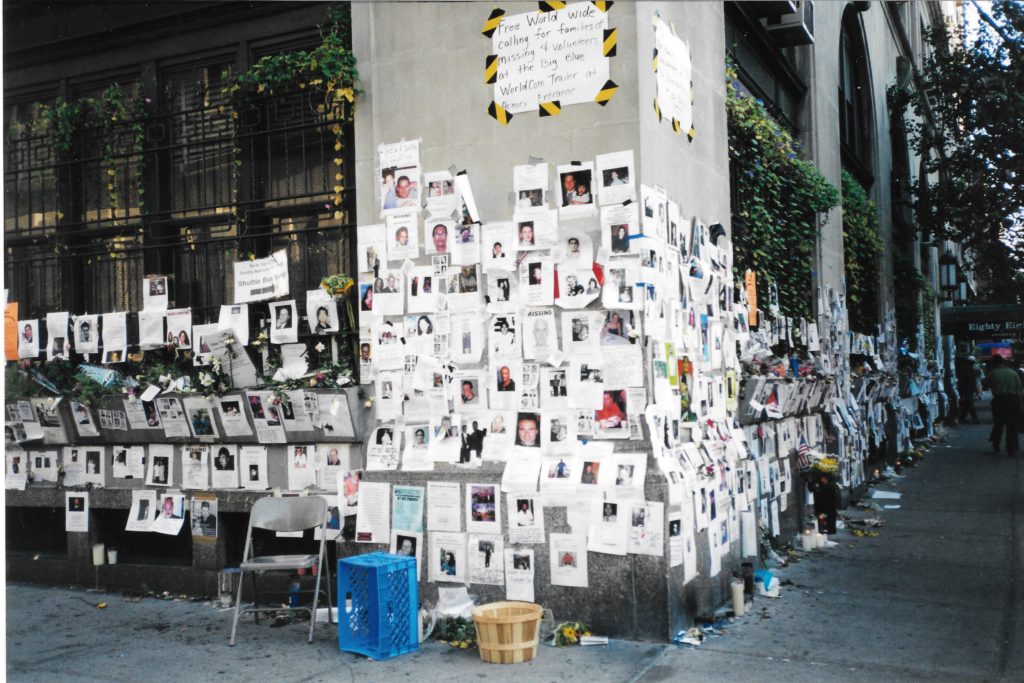

69th Regiment Armory in 2001

-

-

69th Regiment Armory in 2016

Contemporary psychological research puts the development of a capacity for stable, long-term memory in children at around the age of seven; events that occur prior to that point are subject to what is known as “childhood amnesia.” This means that anyone born from the mid-nineties onwards has no direct autobiographical memory of 9/11, for historically indifferent reasons of neurobiology.

In the literature section of the gift shop, a glossy book promises to make 9/11 comprehensible for toddlers. It tells the story of a city of moles, hailing from all walks of life: Bigmoles (politicians), Starmoles (celebrities), more. The protagonist is a blue-collar Mole who is on hand when the two tallest spires in Mole City are attacked by roving dragons. While moles in office attire run screaming from the collapsing towers, he throws on his hardhat, grabs a shovel, and searches for survivors. His hard work and piety – throughout, he prays to “Overmole” – transform him from a lunch-bucket Everymole into a “Bravemole” who is just as important as his more glamorous peers. Once storytime is over and the kids tucked in, parents can turn to the 9/11 Commission Report, also on sale, which will explain September 11th to them as a convoluted tale of institutional breakdowns and intelligence failures.

-

-

Greene St. and Spring St. in 2001

-

-

Greene St. and Spring St. in 2016

Looking at Evan’s photos side-by-side with those of my parents, what strikes me most is how little has actually changed. The streets are still full of uniformed police and camouflaged soldiers, bulldozers and construction equipment. They are no longer here for First Response and to clear away rubble, though. Instead, they’ve been deployed for security and omnipresent construction. Apart from that: there are more surveillance cameras than ever before; pencil towers rise on the skyline where previously there were tenements; fashions in clothes and cars have changed. But otherwise, all looks the same, even if it feels so different. The city rushes onwards. How could it not?

-

-

Century 21 on Dey St. in 2001

-

-

Century 21 on Dey St. in 2016

I think of a story told to me by someone I trust, and who was privy to the proceedings. After 9/11, a tenant in one of the few residential buildings near Ground Zero expressed reluctance to return to his deluxe apartment. Debris and body parts had landed on the parapet beneath his windows, but all that had been cleaned. The problem, he told the building’s Board, was the ghosts. He was a stockbroker, a consultant, a hedge-fund guy, some kind of Master of The Universe – but also a Buddhist. According to him, hungry ghosts, pretas, howled outside his window, full of rage and despair, streaming upward from the shattered hulks of the towers. Their pain was agonizing, and he was considering breaking his lease. But – if there was a way to lower his co-op fees, then, perhaps, he could be persuaded to stay…

-

-

Duane St. and West Broadway in 2001

-

-

Duane St. and West Broadway in 2016

One way or another, everyone, it seems, has a 9/11 story, real or imaginary. With the exception of the testimony of those directly touched by the event, and especially the experiences of those who grieve, I admit I have grown to find the sheer overwhelming number of such stories hard to bear. Part of this is a reaction against the political uses to which a national 9/11 narrative has been put; part of it is disgust at the insipid versions peddled by the culture industry – the Reign Over Mes, the Extremely Loud and Incredibly Closes. But more than anything else, I find myself chafing at the claim to self-evident value that we Americans seem to have attached to our confessional disclosure, our impulse to personalize the event, to make it about us. At its most benign, that “about us” is merely trivial: as though watching CNN on a September morning and thinking what everyone else was thinking and saying – “This changes everything” – was somehow unique or profound. But more insidious, I think, is the temptation to personalize in a way that makes everything all about us on our own terms. We want so badly to package 9/11 as what we want it to be – and accordingly to silo away the unpleasant details of what led to it, and what we claim it led us to do. The soft narcissism of spotlighting our individual participation in history, however peripheral, flows into selective remembering, and motivated forgetting.

-

-

Engine Company 8 and Ladder Company 2 on 165 East 51st St. in 2001

-

-

Engine Company 8 and Ladder Company 2 on 165 East 51st St. in 2016

In the 9/11 Museum, a quote from Virgil’s Aeneid looms large: NO DAY SHALL ERASE YOU FROM THE MEMORY OF TIME. The wall bearing the inscription separates visitors from the Repository that contains thousands of as-yet-unidentified human remains. It is a powerful statement – but also a disconcerting one, since the “you” in its original context refers not to civilians or innocent victims of wanton violence, but instead to a pair of mythical Trojan warriors who are slain in battle after themselves butchering scores of sleeping enemies.

-

-

Engine Company 22 and Ladder Company 13 on 159 East 85th St. in 2001

-

-

Engine Company 22 and Ladder Company 13 on 159 East 85th St. in 2016

When the memorial quotation was first made public, and some controversy ensued, the museum’s director appealed to the “museum’s overall commemorative context.” This context, it was argued, trumped the quote’s original one. But demarcating “context” is a slippery project. The boundaries of the museum’s walls, or of even Lower Manhattan, are not the only contexts. There are others. Fifteen years of global war, hundreds of thousands of civilians killed in Iraq alone, thousands of American and allied soldiers dead, more. As the company of the dead swells, and boots leave the ground in one theater only to touch back down a few years later, our capacity to differentiate individual campaigns threatens to break down. Possibly, in decades to come, remembering the distinctions between them will seem a merely academic matter – as relevant as the distinctions between the multiple wars of Rome and Carthage to which Virgil’s epic alludes.

NO DAY SHALL ERASE YOU FROM THE MEMORY OF TIME. We may stand in front of the museum’s inscription and try to forget, but this epitaph for the World Trade Center’s dead is inextricably yoked to unapologetic praise of killing in the service of imperial destiny. Perhaps this is the right quotation to use after all.

-

-

Spruce St. and William St. in 2001

-

-

Spruce St. and William St. in 2016

In the past months, two major American airports have gone into lockdown in response to rumors of nonexistent mass shootings. Police have deployed and civilians have stampeded, some falling down staircases as they fled. In both instances – at LAX and JFK – the prompt for the panic turned out to be comparatively innocuous, everyday events: boisterous people watching televised sports, a man in an outlandish outfit. Yet travel ground to a halt nonetheless. The very real possibility of violence by either authorities or misguided Good Samaritans seems to have been averted largely out of luck.

These eruptions of collective hysteria suggest the sheer intensity of fear percolating just below our otherwise banal daily activities. We may spend $7 billion annually on the Transportation Security Administration, but beneath our orderly circulations of bodies and commerce, insecurity crackles like a live wire.

-

-

East 26th St. and Lexingon Avenue in 2001

-

-

East 26th St. and Lexingon Avenue in 2016

In his writings after the 9/11 attacks, Osama Bin Laden was frank about his agenda: to entangle the United States in foreign policy quagmires, to bleed its treasury dry, and, above all, to ignite the violence and venality he saw as existing beneath the surface of American society. What more efficient model of terrorism could there be, after all, than one that would lead your target to terrorize itself?

Fifteen years after 9/11, it seems incontrovertible that these goals have been realized, and that this state of affairs has been achieved. Perhaps we did not need Al Qaeda to get here; perhaps we would have gotten here on our own all along. Granted, Bin Laden’s other ambitions – like the withdrawal of American forces from Saudi Arabia, or the establishment of pan-Middle Eastern Salafist regimes – have not been realized. It would be incorrect, in this sense, to say that the terrorists have “won.” Airplanes still fly above Manhattan, and New Yorkers no longer reflexively duck. But we would be forgetting our own very recent past and ignoring our present if we did not concede how much, and how badly, we have lost.

An office in one of the World Trade Center properties on September 18, 2001

***

Evan Simko-Bednarski is a journalist and documentary photographer living in Brooklyn, N.Y. His work has appeared in The Nation, The Atlantic Wire, the Columbia Journalism Review, and elsewhere. He tweets as @simko_bednarski and his photography can be seen at http://www.simkobednarskiphoto.com/.

Patrick Blanchfield is the Henry R. Luce Initiative in Religion in International Affairs Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Center for Religion and Media at NYU. He holds a PhD in Comparative Literature from Emory University and is a graduate of the Emory University Psychoanalytic Institute. He writes about US culture, guns, and politics at carteblanchfield.com and is on Twitter as @patblanchfield.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.