"Blessed are those who have not seen": Image and belief in Jonas Bendiksen’s The Last Testament

On the disappointment of seeing and (not) believing

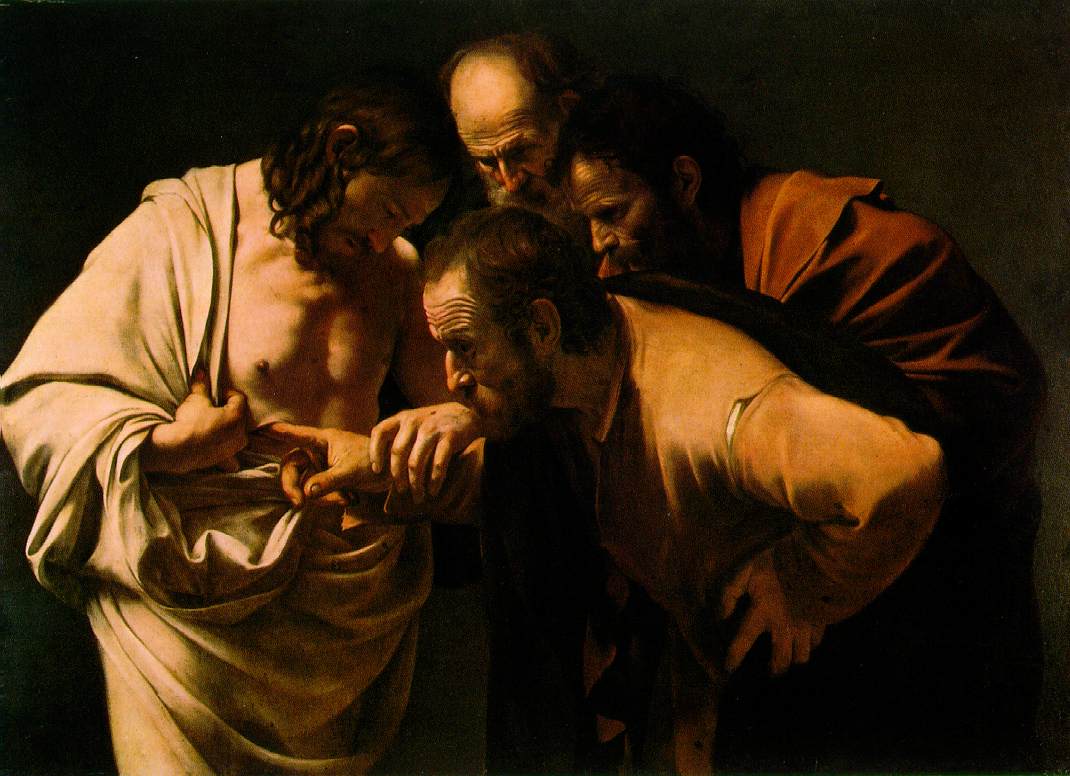

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Caravaggio

The Gospel of John records two curious and dramatic encounters that followed Jesus’ crucifixion. Nearly all of Jesus’ disciples secretly huddled together a few days after his death when he, miraculously, appeared in their midst. But one of the disciples, Thomas, was absent and couldn’t bring himself to believe what the others reported to him. He leveled the skeptic’s ultimatum: “Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe.”

Wonder of wonders, then, when Jesus appeared to Thomas some days later. One can imagine (with Caravaggio) an incredulous Thomas suspiciously probing Christ’s yonic wounds, while also remembering Thomas’ earlier declaration was more about the touching than the seeing. Thomas’ fingers, rather than his eyes, felt out the path of belief: “My Lord and my God!”

Jesus, in turn, shifted the terms of engagement. “Have you believed because you have seen me?” he asked Thomas, whose fingers were, perhaps, still moist from his inquiry. Then came the kicker: “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet still have come to believe.”

The Gospel of John asks us to be convinced by Thomas’ belief, which is another way of saying that we are asked to make do with words alone. Jesus, at least, wanted Thomas to feel the weight of our disappointment at not being able to touch the wounds of a resurrected body. While it is tempting to put a glowing modernist halo around Thomas’ skepticism — to see in his initial question some ancient version of “pic or it didn’t happen” — would we be any more convinced if we, somehow, had a photograph of the exchange? And to ask that question is to miss the heart of Thomas’ desire, which was to let his fingers feel the truth of what others already believed.

Jonas Bendiksen’s documentary photography project, The Last Testament (Aperture/GOST, 2017), opens with an invitation: imagine yourself as a believer, as someone whose world is ripe with the hope that salvation — some divine rescue — is coming. By making such an invitation, Bendiksen (b. 1977) welcomes those who, like he describes himself, are people “of little faith.” He envisions that those who will behold the images of these Christs have, on the whole, left religious belief behind. For them, such belief is the mere spirit of a European past whose gothic skeletons become barer by the Sunday. He asks, however, if they might like to step into what it used to be like. For back when belief was possible, the world was full of glorious possibilities and promises, like that one day, Christ would return to create a new heaven and a new earth.

The irony that Jesus, before whom, we are told, “every knee will bow in heaven and on earth” was undeniably parochial — quaintly magisterial — infuses The Last Testament. Jesus, of course, lived at a certain moment in history, under Roman imperial rule, speaking a single language, and working, presumably, as a carpenter. What if that Christ returned, but to Zambia, or Japan, or the UK, with all the contingencies that come with living in those particular places at this particular time? What if we could see him and, in seeing him, perhaps believe?

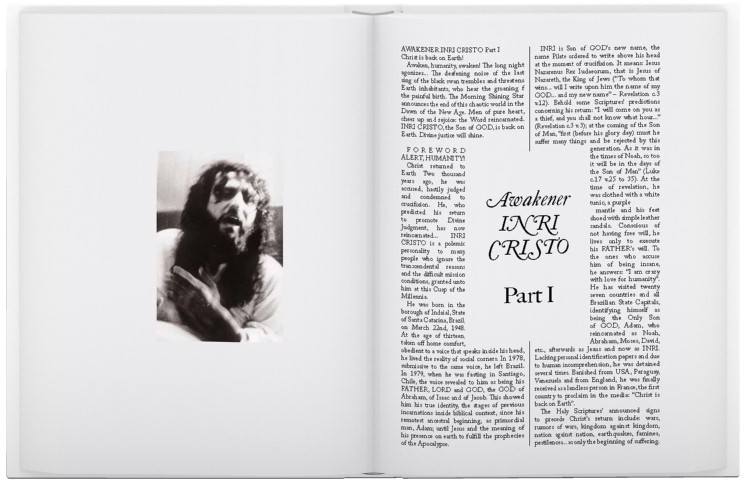

Bendiksen’s project is, in one sense, an accomplished Norwegian-born Magnum photographer’s documentary exploration of seven men who believe themselves to be Christ, returned in the flesh. But to conscribe it merely to documentary photography would be to ignore both the project’s mode of expression, as well as the spirit that infuses the whole of it. Organized into seven chapters, with each “Christ” the subject of his own chapter, one encounters each Christ’s words — and often a good many of them — long before one beholds his image. Printed on gilt-edged scritta paper, the testaments of these Christs are treated to the biblical double column layout of more ancient scriptures. The provocative truth of the project emerges through this creative use of affect. Is this holy? Is it true?

I doubt the texts will prove convincing to many people, even if they take time to read these testaments, which are part screed, part local history, part geo-political critique, and part biblical exegesis. Who, for example, does Bendiksen really expect to trace out David Shayler’s byzantine efforts at demonstrating why he must be regarded as the Lord Jesus Christ under English Common Law? But to dwell on the written words of these Christs is to miss the point of why their words seem to be there in the first place, which is to confirm, one assumes, our bias.

It is hard to imagine someone so exotic to a modern, secular European than a man who is not only deeply committed to his religion, but who has the audacity to argue that he himself is Christ, returned in the flesh. So, we are made to puzzle at a compendium of odd claims. Do these people really believe this stuff? The testaments within The Last Testament exotify even as they create an ethos: they could be something holy. For, what if that first Jesus — an uneducated peasant from the margins of the Roman Empire, some 2,000 years ago — had left a 50-page treatise? To think of such a question, which haunts The Last Testament, is also to remember the fact that we don’t believe in that stuff – at least now, anyway.

When we quickly thumb through the words to find the images do we, then, see belief? If so, that belief seems to separate photographer from subject, for that difference is the occasion for Bendiksen’s photographs. If this is the case, then “belief” reproduces the exotifying gaze that infused so much colonial ethnographic photography whose images displayed the superstitious, baffling, and altogether odd subjects who, metropolitans were told, actually did these things, if they could believe it. And those civilized metropolitans did believe it, and it helped to distinguish modern from superstitious, photographer from photographed.

Bendiksen does not entirely shed this tone, but he seems aware of its history, the burden of this legacy. The Last Testament is less a dismissal of that impulse and more a transmutation of it, for, in being invited to believe, we become implicated in these incarnations. The photographer’s gaze is not so much exotic as envious — an almost nostalgic longing after belief. Wouldn’t it be nice if it were still true that — in the midst of the wars, famines, and destruction of our common home — that someone could save us? It is a desire for that truth that Bendiksen wants to show us. But, as Pilate famously queried, “What is truth?” Can a photograph capture the unreality of the incarnation or the resurrection any better than words?

Bendiksen’s opening image — of “Jesus of Kitwe” — fixes our attention on the eyes of a Zambian Christ who looks up and away, cast in a fierce hope. With a depth of field so shallow that even the tip of his nose starts to blur, we behold his eyes glowing with a haunting vermillion confidence. If we see in it something saintly and ethereal, some evocation of the eternal, the next image jars us into the contingencies of his incarnation: in this case, a worn blue sedan parked in a dirt lot; faded, hand-lettered words “LORD OF LORDS” mark the rear door. And we are immediately struck by the burden of living the paradox of Christ: the eternal contained in time and space.

Subsequent Christs have their own ways of bearing this contradiction. In the next chapter, INRI stands in a hotel room, dressed in a simple white frock, a plump braid of white thorns crowns his head, which is backlit with a heavenly ochre. His fraught countenance turns from the open window, and with hands raised in innocent defensiveness, one feels his bemused discomfort at being exposed to the rainy Brazilian cityscape below.

Then, on a typically overcast British day, David Shayler walks behind a nearly life-sized statue of the crucified Christ outside of a Sainsbury’s convenience store. His hands pressed into his trouser pockets, he stares off to the left of the photo, unable to be bothered to look at the crucifix emplaced in the sidewalk in the center of the frame. One feels the ambivalence of being a Christ in a country that has said quite clearly over the past century that they’ve already given that whole thing a go and have had quite enough of it, cheers. Who, then, could blame this Christ for rebuffing dubious moderns with “You’re not interested in my Twitter feed, I say fuck off then, don’t read it!”?

Jesus Matayoshi isn’t so willing to leave it to others to make the decision. In some sense, Matayoshi exists in severe contrast to the cacophony that surrounds him — the moral laxity of the Japanese urban masses’ global capitalism — but he also cannot help but contribute to the noise. We see Matayoshi standing atop his minivan, straining his voice into a microphone, scolding the ignorant crowds beneath him with a singular condescending finger. Bendiksen frames the moment at an angle such that the only plumb line seems to be Matayoshi’s spine, while the blissfully absorbed cosmopolitans carry on, unconcerned that they could never hope to set themselves straight. We ponder the desperate impossibility of their ever hearing him, even as we don’t bother to listen either.

Apollo Quiboloy feels like an apocalyptic interlude, a Christ so consumed with power that Bendiksen can only focus upon the accoutrements of his televised presence: hands deliberately clasped over a trim gilt-edged Bible, revealing a luxury sports watch; a private jet silhouetted against the blue sky; spraying bullets into a jungle with a machine gun. One wonders whether this is the Jesus who has “come not to bring peace, but a sword.” Or perhaps this is a Christ who wishes he could return to that mountain top and take up the devil’s offer from all those years ago, for he was promised “all the kingdoms of the world,” after all, and it might as well start with the Philippines.

If Bendiksen shows us the artifice of Quiboloy’s authority, the implicit terror of his performance, then in Moses Hlongwane we are endeared by Christ’s improvisations. In an almost-finished house, with mismatched flooring and spliced wires, or in the dark sunglasses and gaudy sequins tacked onto repurposed dress shoes, we see a Christ who cobbles together his divinity. This Christ bursts with a joyous panache into such a dazzling assortment of what’s at hand that it might be easy to overlook the fact that the rhinestone lettering on his cap — “JESUS” — is slightly askew, or that one of the tacks securing the lace lining of his glistening shoes has fallen off.

In the end, however, Bendiksen can’t take too seriously a Jesus who preaches to the Japanese urban masses with a megaphone from the top of a minivan, or a Christ who gets carted around a meticulously tended Brazilian garden every day. But in the quaint Siberian messianic communes founded by Vissarion, he seems to have found something that resonates. Here, his earlier suspicions about the invention of other Christs’ claims begins to soften. Those who follow Vissarion have crafted these communities out of the forest. As they share the food, piled high across long tables, Bendiksen’s fingers seem to touch something, and we wonder if he might blurt out a surprised confession. Until, that is, the final frame captures this Christ on a snowy hillside, benevolently overseeing the adoring crowds below as he makes his way to or from a carved wooden throne, shaded with a scarlet umbrella, and we wonder if we can almost hear the photographer’s sigh as he realizes that he probably wouldn’t fit in after all.

We are shown each of these unique Christs and given the suggestion that they might be holy, even if it is merely a biblical simulacrum. Even if one of them really is holy, we can’t take any of them on their own terms, for, in setting an array of Jesuses before us means that their truth claims have all been relativized. But to focus on that is to miss a crucial point, for what is sacred here is the possibility of having options. Bendiksen seems to say, “Not that it really matters, of course, but which Jesus do you like?” And this is the curse of the modern blessing: how to choose? To read The Last Testament, then, is to imagine a world in which Jesus mattered. It is to feel ourselves pulled into a different, more enchanted, history, even as the photographs make us encounter Christs in the present.

It is to our present that these Christs speak; it is our present that they critique. They hope, by their very presence, that they will cast into relief the partiality and paucity of the existing options, of what is being said and done. The incarnation surely implies some discomfort at the present state of affairs, whatever that present is.

Even as Bendiksen so creatively and provocatively captures these contemporary Christs, I wondered what was occluded by his preoccupation with the present. We get little sense of the particular, local histories into which each of these Christs has been incarnated. What of new religious movements in Russia? What of the history of independent, prophetic, and revolutionary movements in the Zambian Copperbelt from the colonial era? What about the history of Christianity in Japan, or the rapid growth of Pentecostalism in Brazil? There’s some consideration of why these particular individuals believe themselves to be Christ returned, but there is no consideration of the how — which is to say, these Jesuses exist, mostly, without history. Instead, they appear as idiosyncratic global moderns who have, somehow, managed to still inhabit a world of belief. But, if this difference is marked merely by belief, how much of an exception are they? And to whom? Perhaps those of us who are among the disenchanted, are the exotic minority.

If there is a thread throughout the work, maybe it is not so much belief, but disappointment. The world is in need of salvation, and Bendiksen tempts us to recall how nice it felt when we believed that someone would come and set it right. But what if any version of the salvations described in The Last Testament actually came? Do we really long for Jesus Matayoshi’s fierce and swift justice, his weeding out of the sexually impure and the morally corrupt? Would we be willing to live according to the strict communal code of Vissarion’s Siberian villages?

The allure of salvation is surely its clarity, certainty, and hope. But to be saved is to not be in control. To be saved is to have a radically different set of power relations — ones that are determined by another, which means that one of the gifts of salvation is not having to figure it out. It is to forego choice. This figuring it out is the exhausting work of modernity, and we despair as we realize that, for us, salvation is bound up with the choice of working it out for ourselves, which means that we have to get busy making up how we might go about doing it.

While Bendiksen shows us Christs in the making, Christs finding their ways among us, the reader also comes to envy them, for they seem to be carried along by something that ultimately feels less of their own making. They believe that salvation is coming. But for many of us, the implied tragedy of Bendiksen’s project is that it doesn’t matter how many divine pictures we see because we wouldn’t know which photo would have us believe that we look out onto something other than an indifferent universe. And even if we did behold such an image, we might find ourselves doubting it with Kafka: “There’s nothing so deceiving as a photograph.” Perhaps that is why Christ called blessed those of us who couldn’t see him, which leaves us flipping through Bendiksen’s gilt-edged paper with the dry fingers of an unbelieving Thomas, imagining ourselves not being disappointed with the world we’ve made.

***

Jason Bruner is an assistant professor of global Christianity in the School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies at Arizona State University.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.