Blackness, Self, and Non-Self in Buddhism

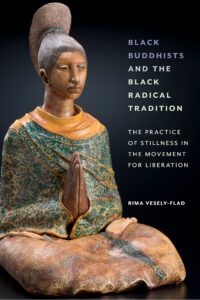

An Excerpt from Black Buddhists and the Black Radical Tradition

(Image source: Stocksy United)

The following excerpt comes from Rima Vesely-Flad’s book Black Buddhists and the Black Radical Tradition: The Practice of Stillness in the Movement for Liberation, published by NYU Press. The book explores how Black Buddhists in the United States have used Buddhist teachings to deal with living in a white supremacist society.

This excerpt comes from the book’s fifth chapter. The section explores how Black Buddhists have interpreted the Buddhist concepts of “self” and “non-self” to find psychological and spiritual liberation within a deeply racist world.

***

Blackness, Self, and Non-Self

Rather than thinking of non-self as a destination or ultimate truth, Sebene Selassie says, we need to be able to relate to the reality of the self and the truth of non-self at the same time.

“The Buddha was asked if there is a self or non-self. He wouldn’t answer because he said ‘that’s not the right question.’ He pointed to the functional need for connecting or relating to the self. It’s not like he walked around and didn’t refer to himself or didn’t have reference for others. He said those are necessary designations we need to move through the world. There is self, but there’s also non-self. . . . He wasn’t saying that non-self is someplace we have to get to and then we can let go of self. He was pointing out that we must develop an understanding of non-self, this is a mark of existence too, in the same way that suffering is a mark of existence. But he also said that there’s freedom from suffering.”

In connecting and relating to the self, the body is a conduit for liberation. At the same time, Lama Rod Owens, a teacher in the Kagyu Tibetan tradition, relates the metaphysical understanding of self to political, psychological, and spiritual liberation:

In connecting and relating to the self, the body is a conduit for liberation. At the same time, Lama Rod Owens, a teacher in the Kagyu Tibetan tradition, relates the metaphysical understanding of self to political, psychological, and spiritual liberation:

“In Buddhism, enlightenment isn’t the extinguishing of the self. It is the recognition of the self. It’s the recognition of the illusion of self. If we did not relate to the self, to this sense of ego, then we wouldn’t be able to be in a relationship to people around us. Because everyone in the world communicates through ego. We relate to reality through ego. So if I were to obtain enlightenment—and I hope to at some point—but if I were to obtain enlightenment, I would still be very connected to ego, especially if I’m trying to liberate others from this reality. So it’s not the ego, it’s not the self that is the issue. It’s our relationship [to those ideas]. . . . Our relationship gives meaning to things around us. The thing itself doesn’t have meaning. This kind of basic work that I’m always engaged in is this balance between self and non-self, and how that relates to social liberation, and how social liberation ties into ultimate liberation.”

For Owens, as well as other Black Buddhist teachers, mindfulness of the body is an essential aspect of liberatory practice. Pamela Ayo Yetunde states,

“In the practices of mindfulness of the body, there’s never [a teaching of] ‘be mindful of the capital S self.’ . . . So [for some] it somehow has become this interpretation or teaching that the body doesn’t exist. But I don’t believe that’s the teaching because there’s so much focus on mindfulness of the body. Those two truths can’t coexist with all the focus on meditation and mindfulness of the body—when to eat, how to sit, so I don’t believe that no-self means no body. And I think that is destructive teaching actually.

The way that I look at it now is that no self means ‘try not to become a narcissist.’ . . . Don’t be so focused on ego clinging that you become selfish. When we look at the teachings of the Brahmaviharas on compassion, equanimity, loving, kindness, and sympathetic joy, when you engage in those practices deeply, it makes you selfless; it cultivates selflessness, and so that’s really how I see no-self. It means selflessness . . . attention towards the well-being of others.”

The fact of constant change—impermanence—of all phenomena, including the self, illuminates that racial constructs of the Black body are empty of substantial meaning. In short, to embrace the teaching on non-self is to recognize that degrading interpretations of Blackness are superficial labels, rooted in ignorance, that historically were exploited for expedient purposes such as land theft and colonization, slavery and forced servitude, and constructing whiteness as intellectually and morally superior to Blackness. In the teaching on non-self, the artificiality of constructed realities is starkly illuminated. To deconstruct the self, not only as a series of always changing and shifting aggregates, but also as a set of degraded images originating from a deluded white supremacist mind, allows practitioners to claim the freedom inherent in dharma teachings. Constructs are simply constructs. They have no basis in reality; nor are they liberating. These constructs form part of the causes and conditions of suffering, but are not hard and fixed facts, eternally believed and internalized. Thus, Black practitioners can shift interpretations of their constructed selves in the movement toward their liberation.

Ruth King, a teacher in the Insight tradition, embraces the teachings on anatta as liberating for people of African descent:

“The teachings on anatta—non-self—are an important inquiry for people of color—those of us who’ve [had] their sense of self ripped away from them or haven’t had a chance to shine or be inwardly affirmed in a meaningful way. We question and doubt ourselves. We don’t know if we do this because of race or if it’s just the human condition.

Self and non-self are wrapped around the Buddhist teaching on ultimate and relative reality. In brief, you need a self (relative reality) to know that you’re not a self or to know you are liberated (ultimate reality). In other words, you need the body in order to wake up.

In the Buddhist teachings, non-self is not that you are not a self, it’s that you’re not a self that you can solidly rely on. The self is constantly changing—a series of processes or aggregate experiences. Change is all there is. When we understand this from our practice, we can soften the grip that identity hardens in our hearts and minds. We can know a deeper freedom, despite conditioning, from the inside out.”

For Black teachers with long-term practices, personally relating to dharma teachings can illuminate obscure or potentially threatening passages, especially in a society in which Black people have been dehumanized. Kate Johnson, a teacher in the Insight tradition, says,

“What are the deep kind of awakening experiences that we’ve had, and do we or do we not teach from that place? Some of my most profound experiences in meditation around this [teaching on anatta] have been deep experiences and insights into emptiness and selflessness, and the interdependent, not solid, nature of self. And also the fact [that there is] no central command system for that self, that the mind actually is not that. I don’t usually teach that. When I can, my favorite places to teach are within POC [communities], the community of women, and queer communities—that’s what I love. And I feel like when I’m in mixed company or when I’m teaching to primarily white audiences I don’t often speak about selflessness or anatta because I worry that it’s going to be fuel for spiritual bypass.”

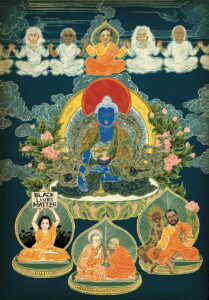

(Image source: Yuko Shimizu)

“Spiritual bypass” refers to using spiritual teachings to avoid psychological and social problems in one’s self or environment. For people of African descent, the challenge of relating to non-self is less about “spiritual bypass” and more about relating to language that suggests non-personhood. Denial of Black humanity undergirded laws and social practices during centuries of colonization and formation of the United States as a nation-state. Thus, the language of “non-self” can erect an emotional hurdle that is important to address with nuance. Unique Holland, a long-term practitioner in the Zen and Insight traditions, describes her first encounter with the teachings on non-self. “[We live in a society in which] white people are the norm. There’s a racialized class distinction. And so this idea of no self had all of this packaging . . . in a way that was distinct from the kinds of oppression and mask making that was expected of me outside of dharma spaces.” The “norms” to which Holland refers are the constructed norms of whiteness as superior and Blackness as degraded. The teaching on non-self, for practitioners such as Holland, has the potential to further reiterate degradation. Yet for Black Buddhist teachers, the liberation found in the teaching on non-self is akin to the liberation encountered in the Black Radical Tradition: it is possible to deconstruct the falsely constructed Black body and claim one’s (relative) self in positive, affirming ways. Moreover, in Buddhism, it is possible to affirm one’s Blackness as one—but not the only—stage in the process of spiritual, psychological, and political liberation. In the practice of letting thoughts fall away, and entering into meditative concentration, the falseness inherent in the mundane world fades to background noise, and the experience of mental stillness arises, even briefly, as the path to liberation. Thus, dharma practice can be seen as living into the aspirations of the Black Radical Tradition: practitioners who enter a realm of mental stability are no longer in reaction to white supremacist constructs and messages. Rather, they can see the delusions inherent in white supremacy and observe but do not react to the false constructs inherent within those delusions.

In their embrace of the teachings on non-self, furthermore, Buddhist practitioners of African descent elevate core teachings on interdependency or interbeing. In the Zen tradition, “non-self” is also interpreted as teachings on interrelationship. Zenju Earthlyn Manuel, a teacher in the Soto Zen tradition, writes on interrelationship in her meditation The Way of Tenderness: Awakening through Race, Sexuality, and Gender. Manuel acknowledges the “profound interrelationship that sustains our existence” and states that “interrelationship is inherent to living.”

“No-self means that other people are involved. That’s what no-self means. It’s not just you. It should say not just yourself, rather than no-self. It means no-self in and of itself, like there’s nothing happening here. It’s relational, and that’s why I say there’s no-self, there’s no just you.

No-self has no substance. . . . And so, you have to talk about your life back to where you started from: how you’re living and who you are, so you can understand the suffering. You have to have some[one] to study. You can’t just walk around, go ‘there’s nobody and there’s nothing and there’s emptiness, and so I just sit here and breathe.’ How long will that last?

I think that no self is really important to understand, especially in Zen, and I talk a lot about it because they [other teachers] use it so much to negate the lived experience, but it’s saying it is the lived experience. No self is interrelationship. No self is interrelationship, it is interbeing.”

Manuel emphasizes that teachings on non-self give practitioners an opportunity to study their own lives: to look within and understand how they arrived at different experiences and identities. Rather than negating the experience of being human, the teaching on non-self is a teaching on learning from one’s lived experiences as well as how relate to other persons in an aware and interdependent way. Similarly, Chimyo Atkinson, a former resident monk at Great Tree Women’s Zen Center, states,

“To say non-self is kind of negative. [The phrase] is kind of empty because self in my understanding is greater than what we see as contained in this body or what we see is contained in this head. It includes all of your surroundings, everything, all the beings that you are ultimately connected with, because there’s the big self. The self that is included in all of this universe. We are not separate from anything. To say self is to separate from all myriad beings that are out there. And that’s our big delusion right there.”

Understanding the teaching of non-self in relation to the social world, Owens says, fosters deeper understanding of one’s own life—as real and in relationship, as a construct and an illusion, and in relation to ultimate reality:

“The ultimate truth is non-self. But the relative truth is self. So one of the things that at least in my practice and also throughout the dharma is that in order for me to earn my experience of the ultimate, I have to actually earn the experience of the relative. So I have to come really close and really solid into what my experience of having a self is. Because once I get really curious in this idea of self, I begin to understand how to actually undo the self, and undo my fixation on the self. I think the self is so deeply, deeply entwined in a way of being in the world and I have to actually understand the mechanisms of the self in order to transcend the self.

So I can start speaking in ways of very general non-self terms, but actually that’s going to be the root of increasing my suffering, of increasing my suffering on the relative, because I just don’t understand the self enough in order to move through it or to transcend it yet. But the ultimate is always on the horizon. So I can talk about the self, but I also know at the same time there is no self. This is the tricky part of integrating justice and dharma. Both of these ideas have to be held together. The relative and the ultimate. You can’t skip around to either-or. You have to be right with both of those always at the same time, and then that actually begins to help us move more towards the ultimate.”

Rima Vesely-Flad, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Religion and Philosophy and the Director of Peace and Justice Studies at Warren Wilson College. She is the author of Racial Purity and Dangerous Bodies: Moral Pollution, Black Lives, and the Struggle for Justice.

***

Interested in more on this topic? Check out our conversation with Rima Vesely-Flad in episode 24 of the Revealer podcast: “Black Buddhists and Healing the Traumas of Racism.”