Black Women Getting Free

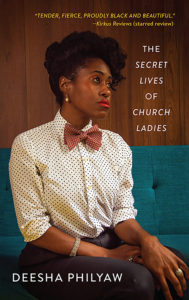

A conversation with acclaimed author Deesha Philyaw about her award-winning book The Secret Lives of Church Ladies

(Painting by Jonathan Green)

One dreary winter’s evening, I cracked open a book of short stories that had been on my desk for months. Upon reading the opening pages of the first story, “Eula,” I knew this was a text unlike any I had encountered. There it was, in beautifully descriptive prose: the glory, the trauma, the joy, and the pain of my experience as a Black girl who grew up in the Afro-Protestant tradition. The book was Deesha Philyaw’s The Secret Lives of Church Ladies. And as a dear friend recently said, “it’s still dealing with me.”

The Secret Lives of Church Ladies is a collection of fictional stories that showcases the perspectives of Black women in what’s colloquially called “the Black Church.” Though history teaches us that there is no singular Black church and Black denominations vary greatly, Philyaw writes about how Black Christian women experience these communities. Addressing a range of topics from sexuality, gender, betrayal and sisterhood, to loneliness, grief and healing, Philyaw gives voice to the longings, desires, and dreams of Black women whose narratives have too often been kept at the margins.

Given the book’s astounding critical praise, awards – including the PEN/Faulkner Prize for Fiction – and the news that HBO Max will produce an onscreen adaptation of the book, it seems inconceivable that Philyaw originally had a difficult time finding a publisher. Facing rejection after rejection, Philyaw’s agent, Danielle Chicotti, mused that it was hard not to wonder why so many editors passed on the collection, with each insisting it wasn’t a “good fit.” But one small press said yes. West Virginia University Press gave Philyaw a book contract and the autonomy to write boldly without having to, in her words, “erase Blackness to recognize the universality of Black stories.”

Given the book’s astounding critical praise, awards – including the PEN/Faulkner Prize for Fiction – and the news that HBO Max will produce an onscreen adaptation of the book, it seems inconceivable that Philyaw originally had a difficult time finding a publisher. Facing rejection after rejection, Philyaw’s agent, Danielle Chicotti, mused that it was hard not to wonder why so many editors passed on the collection, with each insisting it wasn’t a “good fit.” But one small press said yes. West Virginia University Press gave Philyaw a book contract and the autonomy to write boldly without having to, in her words, “erase Blackness to recognize the universality of Black stories.”

Raised in Jacksonville, Florida amidst women similar to those she describes in her book, Philyaw’s upbringing in Black southern churches informs her work, even as she avoids direct depictions. She uses stories and memories from her youth in Jacksonville and adulthood in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to enflesh fictionalized plots, while abiding by her own ethical standards to bring no harm to Black women.

With great care Philyaw explores the interior lives of Black women, the passions we are taught to hide, the things we are told not to want. She welcomes the reader into a sanctuary of communal witness, the truths of which, I believe, will resonate in the hearts and minds of those raised in, or in proximity to, Black Christian cultures. I had the opportunity to chat with Philyaw about these themes and more; our conversation has been edited for clarity.

Ambre Dromgoole: Tell me about the title of your book, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies. Who were you referring to and why was it important for you to write about them?

Deesha Philyaw: I wanted to write stories that explore how Black women grapple with getting free of the guilt and the shame and the fear that many of us are taught in church. And how we strive to live as our whole selves after being taught to reject or hide important parts of ourselves, such as our desires. I was writing about church ladies, these are women in the church, and people that I call “church lady adjacent.” When I say “church lady adjacent,” I’m referring to women who have someone in their life who is a church lady, someone close to them who influences them, a woman who has been and continues to be influenced by the church. I chose them because church ladies and church lady adjacents loomed large in my upbringing and, therefore, in my memories.

AD: The idea of church memories reminds me one of my favorite Aretha Franklin moments when she reflected on what church smelled like, which, for her, was “a lot of good fried chicken and homemade rolls and fried corn and things like that.” Can you describe some of your sensorial memories regarding Sundays and church services growing up? Is there anything that especially sticks out?

DP: What I remember most, of course, are the church ladies. In particular, a Sunday school teacher who wore stark whites when she was ushering. They would dress like nurses, because when somebody caught the Holy Ghost they had to catch them. They would even have on the white nurse shoes. It was just something about that whiteness, I mean it was spotless. Then, by contrast, she wore layers and layers of this Fashion Fair makeup. It was almost like seeing a balloon you’re worried is going to pop, for me it was like, “Oh my God. Is she gonna get makeup on that white?!” But it was always pristine. It was just something about that pristine whiteness and those layers of makeup that threatened the whiteness of her clothes. I would look at her and always wonder “what does she look like in jeans?”

Then there was another woman who was single and she was one of the people that carried the offering trays. This woman strutted! I mean she had a walk. As a kid I remember thinking of her as a peacock. Even though I learned later that peacocks are male and it’s right there in the name, the preening and the display that the peacock does. She was like that. Her makeup was on point. It didn’t seem heavy and caked on. She did the dramatic eye, and she was beautiful. She would always wear these beautiful dresses, but there was this one gorgeous cobalt blue that I can still see. I just remember falling in love with that color because of how she wore that dress. She had these heels that seemed impossibly high to me as a kid; they were probably stilettos. It was like the aisle of the church was her runway. She didn’t smile a lot, but she served face. She was absolutely beautiful and carried herself in this very carefree kind of manner that I didn’t always see at church, so it stood out to me. I was curious about her too. I could picture her in jeans, but I wondered if she was happy.

AD: You’ve talked about “the Black Church” being a towering figure in Black culture, no matter if you are in the church or not, and we see that with the various characters in your book. Why do you think it’s such a significant site of cultural formation?

(Image courtesy of PBS)

DP: I believe it’s because the church was free Black people’s first institution of community and belonging. It’s all we had other than our immediate families. We found all this common good there, but that institution was also where we learned constricting binaries. There were these really tight rules of respectability concerning how, especially women, were to behave. This is where we got our very narrow definitions of goodness. Where we got a lot of shame and misinformation around sex and sexuality, and who women are; this is where we encountered double standards around gender that also played out in our home lives and were reinforced in the church. This is where we were also given hope in a world to come. It encouraged women in particular, not just Black people in general but Black women in particular, that any hardships you have, anything that’s unfair or uncomfortable, it’ll all be fine in the next life.

I didn’t feel like it was possible to talk about Black women getting free without the church, and the church’s role in what we’re trying to get free from being front and center. But not the church itself. It was really important for me that the women are the center and the churches were in their orbit, not the other way around.

AD: I co-facilitated a women’s book club on The Secret Lives of Church Ladies. While everyone adored it, some were troubled by what they saw as a negative portrayal of the church. What would you say to them?

DP: When we keep this stuff secret, that’s the prime condition for abuse to go unchecked, for hypocrisy and double standards to go unchecked. The church has done really well in not talking about it, not wanting to air it. In those dark conditions, in that secrecy the harm grows and flourishes.

I would say, as gently as I could, we could have these in-house conversations, sure, but we’re not. When people have been harmed in the church, the harm that the church does doesn’t stay in the church walls. It spills into the culture, so critique of it becomes fair game in the culture. Also, we have to stop worrying about how we appear to white people. My book isn’t the first book to talk about these things publicly and we have got to be more concerned that Black women are hurting than we are concerned about white people seeing that we’ve hurt Black women. We’ve got to care more about the women than appearances.

AD: Last year, in a conversation with Kiese Laymon, you talked about finding pleasure in the darkness of the Bible in reference to “Jael,” both the biblical story and your short story by the same name. Could you say more about why you love exploring this pleasure and darkness?

DP: The darkness, for me, is the mystery, the complexity, and the messiness that’s there. I was drawn to the very personal violence enacted by Jael, a woman who nails a man’s head to the ground! He’s an enemy army general who she pretends to give refuge to and then, in his sleep, she kills him. It’s so personal to kill someone like that. I was curious about her. Where did she get that? What drove her to do it? I get it, he’s the enemy; but that’s still very personal. The level of rage, the physicality of that act. What was the rest of her story? We get her in this moment in time and we don’t know what came before or what came after. I delight in these layers of complexity and subversion. We were told so much of life is off limits to us, so much of our bodies, ourselves, who we are. I take pleasure in looking at what happens if we peek in those places where we’re not supposed to look.

AD: The spirit of Audre Lorde hovers around this book. I’m reminded of a quote where she says “my capacity for joy comes to demand from all of my life that such satisfaction is possible, and does not have to be called marriage, nor god, nor an afterlife.” Similar themes surrounding joy, desire, satisfaction, and freedom show up again and again in your book. Why were they so important for you to portray?

DP: It’s because Black women aren’t encouraged enough to pursue joy and desire and satisfaction and pleasure and freedom in this life. Not for ourselves. We can be about it for the community, we can be about it for our children, we can encourage Black men, but somehow we get what’s left over; we get the dregs. So many of us need to be reminded and encouraged and, in some cases, given permission to pursue these things on behalf of ourselves and our own. We need someone to come along and say this is yours, this is for you. Audre Lorde said self-care isn’t indulgence; for Black women it’s political warfare.

AD: And it’s not always pretty. Sometimes self-care is literally fighting against all these “isms” that are forced on us daily. To say that I am worthy and righteous of being my full self, in spite of all of the things that are going to tell me I’m not.

DP: Including our internal narratives that we often get from our families, that we get from churches that tell us what we should desire, what we should prioritize. It costs us something to say, “No, I’m not going to live that way. Yes, I am going to pursue joy.” We could lose friends, we could lose loved ones, and we can lose our faith. It costs us something. If it didn’t, we’d all be free of it right now. Hopefully, through the characters in the stories, Black women can see that they’re not the only ones going through this and it’s worth it, you’re worth it, the freedom is worth it.

AD: Another theme in the book is that of “home,” whether finding home in someone, in your own body, or in a physical location. What does home mean to you?

DP: I think the short answer is that home is a shifting concept for me. The journey of coming to feel at home in my body – which shows up a lot in “How to Make Love to a Physicist” – that’s a journey that I have been on. I remember when I was pregnant with my oldest daughter, which was the first time I actually loved my body because I saw my body, not in terms of weight or anything like that, but in terms of what it could do. I was growing a human being. How could I do anything but love this body? Our bodies, all of them, are amazing and that was a very pivotal moment for me. This idea of being at home in your body, comfortable with your body: that’s not one that was easy for me. I had to come into that in my adulthood.

AD: When I asked the book club members if the church taught Black women to be at home in their own bodies, all of them, no matter whether they were defending the church or not, said “no, I have not been taught to be at home in my body.”

DP: We’ve talked about the way that the church views of our bodies and the body of Christ, but it’s never presented as a source of pleasure, except in Song of Solomon between two heterosexual married people in this very kind of limited way. It’s not pleasure for pleasure’s sake, not personal pleasure.

AD: One of my favorite stories in the collection is “Snowfall.” Without giving too much away, there’s a part where one of the characters, Rhonda, apologizes to her partner, LeeLee, by saying “just because. . . somebody hurt me doesn’t make it okay for me to hurt you, to not be there the way you need me to be,” which I found to be a powerful moment of recognition, reconciliation, and, later, restitution. Why did you include this moment?

DP: That saying “hurt people hurt people” is so true. In “Snowfall” this is a moment where someone is saying to someone she loves, “this is really hard, but it’s also really necessary for me to break this cycle.” All of us have been hurt or traumatized in some way. What it means to grow up and to do better and to heal involves a moment or moments where we can gather ourselves up in a way that says, “This stops with me.” This is an example of multiple things being true at once. Often it’s, “I was hurt in this way, so now I’m scared.” Or, “I was hurting this way, so I just can’t open up.” Or, “I was hurt in this way, so I can’t see anything but my hurt.” But being in relationship with people, being in healthy relationships requires us to look at our stuff and then to look at how we show up. In this collection I wanted to show that something beautiful was possible, that care was possible. But it’s complicated.

AD: If there’s ever an argument for therapy, it is that it holds a mirror to you. It’s often said that it is not your fault that you were hurt, but your healing is your business.

DP: The book that brought that idea home for me is called Fatherless Daughters. There’s a section where they talk about fatherless daughters in heterosexual romantic relationships, how we show up, what we need, who good partners are for us and what we need from them. One of the men who was interviewed about his relationship with his partner said exactly what you said, saying, “It’s not her fault that this happened to her and her healing is her responsibility, but it’s easier to heal with help and support.” That’s an essential piece. Yes, we’re responsible for our own healing. But are we surrounded by people who are going to support us through that healing?

AD: Healing is nurtured and fostered through community. It’s taking it out of the dark, damp place where bad bacteria can flourish and putting it in the light. You need people to be in that light with you. So I also want to ask you about grief. In “When Eddie Levert Comes,” grief shows up when a daughter is dealing with her mother’s chronic illness. The story shows that longing can be another aspect of grief; it’s grieving what a relationship could have been while illness takes its toll. What do you want people to take from how you address grief?

DP: My mom and my grandmother died in 2005; my father died the same year as well. That was also the year my first husband and I separated and later divorced, which was a lot of grief at once. Just an overwhelming amount of grief. It’s not like a moment in time; it’s ongoing. I still grieve those losses. One of the things that I hope these stories illustrate and that I wish more people understood is that grief shows up in a lot of different ways and it’s unhelpful to expect grieving people to grieve on a timeline. I wanted to show how grief lingers. I wanted people to know that it can show up unexpectedly and in forms we don’t anticipate, but that it’s all valid and, at the same time, see that we can show up better for people who are grieving.

AD: You recently won the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. In your remarks, you said “my stories are meaningful in this present moment because I’ve always looked to Black women to see what’s possible,” after which you named several authors whose footsteps you walk in. Could you say more about this? What possibilities have been revealed to you by looking and writing toward Black women?

DP: Black women writers have shown me how to be unapologetically Black in my work and in my life. That we are enough. They’ve shown me how to love us best of all. They’ve shown me that Black characters don’t have to be sinners or saints. They can be real, complicated, and messy. They can have desires, they can disappoint, and they can have those layers that we love so much. And they can be joyful. All of those things can be true. Even within the same story and even within the same character. Black women writers have shown me how to write fearlessly and when fear shows up, as it does, they’ve shown me how to keep writing anyway.

Ambre Dromgoole is a Ph.D. Candidate in the combined program in African American Studies and Religious Studies at Yale University and a Sacred Writes/Revealer Writing Fellow. Her dissertation is tentatively titled “There’s a Heaven Somewhere’: Itinerancy, Intimacy, and Performance in the Lives of Gospel Blues Women, 1915-1983.”

***

This article was made possible in part with support from Sacred Writes, a Henry Luce Foundation-funded project hosted by Northeastern University that promotes public scholarship on religion.