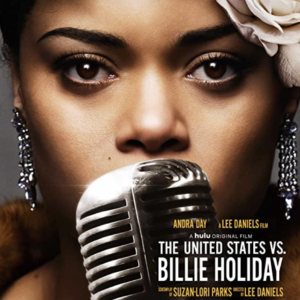

Billie Holiday, ‘Strange Fruit,’ and the Resilient Myth of Martyrdom

A review of the film The United States vs. Billie Holiday and its portrayal of the singer as a sacrificed martyr for civil rights

(Photo: Billie Holiday)

A handful of scenes in The United States vs. Billie Holiday evoke the singer as we see her in a luminous cache of rediscovered photographs by Jerry Dantzig. Taken in 1957, two years before Holiday’s death at age 44, the photos show a radiant artist at the top of her game. Holiday looks like visiting royalty, majestic and serene: here she is in mink, embracing a dazzled well-wisher; here adorned in jewels, commanding regally from the stage. The Dantzic photos inspired novelist Zadie Smith to write “Crazy They Call Me,” a short story told in Holiday’s voice. In the story Holiday contends with reporters and fans who want answers: which brutish man in her life goes with which song, whether heroin makes her voice rougher or sweeter, what went down in her most recent run-in with the law. She’ll entertain their dull questions, say something to make the haunting beauty of her singing accessible and plain. But Smith’s Holiday knows her art is more than the life of a victim, an addict, or a glamorous outlaw set to music. Motherfucker, she silently addresses a conniving journalist, I AM music.

I’d love to hear what this Billie Holiday thinks of British journalist Johann Hari.

Hari is an executive producer of The United States vs. Billie Holiday and the author of Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs, on which the film is based. The United States vs. Billie Holiday finds the key to understanding the singer’s life in the song “Strange Fruit,” her searing, graphic witness to lynching. The film takes and runs with Hari’s sensational claim that the Federal Bureau of Narcotics made it a priority of the government to silence “Strange Fruit” by silencing Billie Holiday, and hunted her to an early death to do it.

Why would the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, an arm of the U.S. Treasury Department, mount a murderous campaign to censor a song? In Hari’s telling, the Bureau’s first and longest-serving commissioner, Harry J. Anslinger, regarded drugs, jazz, and Black America as a single, hydra-headed evil. In 1939, nine years after Anslinger took office, Holiday performed “Strange Fruit” for the first time. According to Hari, Anslinger heard Holiday sing of lynched Black bodies—strange fruit hanging on Southern trees—and heard the opening salvo of the Civil Rights movement. Hari reports that Anslinger issued an order to Billie Holiday to stop singing “Strange Fruit,” and, on the pretext of a narcotics charge, arrested her the next day for defying it. After her release from jail, Hari says, Holiday continued to perform “Strange Fruit,” and Anslinger continued to hound her because of it. She grew ill under the the strain of relentless surveillance and repeated arrests, the last as she lay dying in an East Harlem hospital, liver and organs shot.

The United States vs. Billie Holiday puts the cartoonish Anslinger at the center of the history it invents for Holiday and “Strange Fruit.” Early in the film Anslinger huddles with Joe McCarthy, Roy Cohn, and a pack of racist legislators who nod along to his plan: “That Holiday woman’s got to be stopped. She keeps singing this ‘Strange Fruit’ song!” Anslinger then manages to attend nearly every Holiday performance and stare her down from the front row. At the Earle Theater in Philadelphia, a phalanx of cops under Anslinger’s direction rush the stage as soon as Holiday defiantly cues the opening chords of “Strange Fruit.” A last-minute gag order from Anslinger strikes the song from the program of the triumphant Carnegie Hall concert she plays on her return from prison. To stay out of jail Holiday keeps mum, until a lynching she encounters on tour in the South steels her to defy the ever-vigilant Anslinger and return to performing “Strange Fruit.” The cat-and-mouse game ends at Holiday’s deathbed, where Anslinger arrests her on a trumped-up charge to make sure she never sings “Strange Fruit” again.

The United States vs. Billie Holiday puts the cartoonish Anslinger at the center of the history it invents for Holiday and “Strange Fruit.” Early in the film Anslinger huddles with Joe McCarthy, Roy Cohn, and a pack of racist legislators who nod along to his plan: “That Holiday woman’s got to be stopped. She keeps singing this ‘Strange Fruit’ song!” Anslinger then manages to attend nearly every Holiday performance and stare her down from the front row. At the Earle Theater in Philadelphia, a phalanx of cops under Anslinger’s direction rush the stage as soon as Holiday defiantly cues the opening chords of “Strange Fruit.” A last-minute gag order from Anslinger strikes the song from the program of the triumphant Carnegie Hall concert she plays on her return from prison. To stay out of jail Holiday keeps mum, until a lynching she encounters on tour in the South steels her to defy the ever-vigilant Anslinger and return to performing “Strange Fruit.” The cat-and-mouse game ends at Holiday’s deathbed, where Anslinger arrests her on a trumped-up charge to make sure she never sings “Strange Fruit” again.

The drab effect of the film’s main conceit is to shortchange Holiday’s exquisite genius, identifying the whole of her artistry with the fictive career of a single, formidable song. The United States vs. Billie Holiday also shortchanges the struggle of which “Strange Fruit” is a part. It locates resistance to lynching in the singular heroine and spectacular gesture—if Billie Holiday doesn’t sing that song, a Black character wonders in the film, who will? In this it vastly diminishes the history and depth of Black responses to racist violence, from the dedication of organizers like Nannie Helen Burroughs and Ida B. Wells, to decades of anti-lynching activism by the NAACP, to the quotidian rebellions of all who dared to live lives of beauty, joy, and power, Holiday included, in the face of racial terror.

This much is undisputed: Anslinger’s war on drugs was predatory and racist, and Holiday was among its targets. A riveting film might be made about the parasitic affinity of his Bureau of Narcotics for the world of jazz and jazz artists, including Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, Anita O’Day, Dexter Gordon, and Ray Charles, all of whom fared brutally in Anslinger-era sweeps. So too might a drama of depth be made about the history of “Strange Fruit,” perhaps taking as starting points Joel Katz’s 2002 documentary and David Margolick’s 2001 biography of the song.

What The United States vs. Billie Holiday gives us instead is a new iteration of the myth of Billie Holiday, victim: the “tragic, ever-suffering black woman singer,” in Farah Jasmine Griffin’s description; “the ‘natural’ artist,” in Russell Banks’s account, “who pays for the gift with lifelong suffering and deprivation and, finally, with her life itself.” In The United States vs. Billie Holiday, Holiday suffers not for the gift of her talent—the film is hardly interested in her music—but for her refusal to stop singing “Strange Fruit.” The movie details her downfall in grim, fetishistic tableaux—here she is shooting up in a dive, getting hosed down in prison, weaving and passing out on the street. But it serves up her suffering inside a suspiciously palatable narrative of martyrdom: for defying government orders not to sing of Black lives snuffed out at white hands, Holiday sacrifices her own life.

(A scene from The United States vs. Billie Holiday)

What makes the fiction of Holiday’s sacrifice, centered on a song of extra-judicial killing—of crucifixion, as James Cone insists we see—so easy to believe? Brett Krutzsch alerts us to ways that deeply entrenched, implicitly Christian notions of redemptive suffering have been used to rehabilitate complicated queer lives for public consumption. Thus Harvey Milk and Matthew Shepherd, to be made relatable as fellow citizens whose lives and deaths matter, needed first to be imagined as martyrs whose violent murders somehow yield hope for a more egalitarian future. The United States vs. Billie Holiday likewise fits Holiday’s complicated queer life into a story of redemptive suffering, signposted with Christian symbols, and streamlined for secular audiences.

Let’s return to Hari’s claim that when Holiday “started to sing” the song “Strange Fruit” she was “ordered by the authorities to stop,” and that her “harassment by Harry [Anslinger]’s Federal Bureau of Narcotics began the next day.” Hari’s putative source is a 1947 piece in the music magazine Down Beat he cites at second hand, interprets with latitude, and resets chronologically in order to attach it to Holiday’s first performance of the song in 1939. The article in Down Beat is an interview with Holiday called “’Don’t Blame Show Biz!’—Billie: Daily Press Taking Usual Rap at Trade with Holiday Case.” The Holiday case turned on heroin found in a federal raid on the hotel where she stayed during a week-long run at Philadelphia’s Earle Theater. When the interview appeared Holiday had already been sentenced to jail for possession, but at press time it looked like she might avoid doing time. In the interview, Holiday speaks in her own voice, making the case for leniency. She lists exonerating factors: a desire to kick drugs, her mother’s recent death, the misery of her childhood, and the relentless wear and tear (“one thing after another”) of being Black in Jim Crow America. She adds: “I’ve made lots of enemies, too. Singing that ‘Strange Fruit’ hasn’t helped any, you know. I was doing it at the Earle ‘til they made me stop. Tonight they’re already talking about me. When I did ‘The Man I Love’ [at the New York club she was playing when the interview took place] I heard some woman say, ‘Hear he’s in the jug downtown’”—a reference to her companion Joe Guy, who was arrested with Holiday and held “in the jug” because he couldn’t make bail.

Hari infers from these few lines that it was the federal government, in the person of Anslinger, who ordered Holiday to stop singing “Strange Fruit” in Philadelphia that night, and that the order was or became government policy. But who does Holiday mean when she says “they” in the interview? “They’re already talking about me” sounds like press gossip, or chatter in the New York club where she’d sung that evening. “They made me stop” in the preceding sentence might refer to an unappreciative audience at the Earle (“as usual it only took one cracker in the audience to wreck things,” Holiday says in her 1956 autobiography). It might refer to the drug raid itself that brought her Philadelphia gig to a dramatic end. Elsewhere in the interview she mentions cops and “federal people.” But if federal agents had ordered Holiday to stop singing “Strange Fruit,” she would likely have said so in her autobiography, which she and co-writer William Dufty wrote in part by mining and embellishing the press pieces about Holiday they liked best, including this one.

Where else might Hari have gotten the idea that “Strange Fruit” made Holiday the government’s Public Enemy #1? He might have seen biographer Stuart Nicholson’s unsourced claim that “FBI agents leaned on” one New York City club owner to prevent Holiday from singing an “unpatriotic” anti-war song, “The Yanks Aren’t Coming,” in 1940. Nicholson misattributes authorship of “The Yanks Aren’t Coming” to Abel Meeropol, the Jewish schoolteacher and Communist party member who wrote “Strange Fruit.” Nicholson also claims that the FBI opened a file on Holiday in 1940, even though no items in Holiday’s declassified FBI file date from before 1949.

In 1940 “Strange Fruit” did draw government attention, not to Holiday but to Meeropol. In that year Meeropol was ordered to appear before the Rapp-Coudert Committee, a state senate committee bent on purging Communists from New York public schools. Soviet propaganda had been calling out the hypocrisy of Jim Crow for years—how could America claim to lead the free world with a boot on the neck of its Black citizens?—and the Communist International courted new members by promoting “self-determination in the Black belt.” The Rapp-Coudert committee asked Meeropol whether he wrote “Strange Fruit” at the Communist party’s behest. For his songwriting and activism Meeropol dodged subpoenas from the House Un-American Activities Committee for a decade. The United States vs. Billie Holiday is so careless of Meeropol that it mangles his pen name, Lewis Allan, attributing “Strange Fruit” to Allan Lewis in the closing credits.

According to a memo in Holiday’s FBI file, a confidential source in Anslinger’s office, perhaps Anslinger himself, said it was Holiday’s “notoriety” that brought her under federal surveillance. “The source states that because of the importance of Holiday it has been the policy of his bureau to discredit individuals of this caliber. Because of their notoriety it [sic] offers excuses to minor users.” The publicity-hungry Anslinger found himself making headlines by feeding a national appetite for what he called the “glamorous entertainment characters who have been involved in the sordid details of a narcotic case.” Billie Holiday fit the bill; as Charles Henri Ford wrote in his 1946 “Chanson pour Billie,” she was “hip . . . as a gangster,” “exciting as a holdup,” “disreputable as pleasure,” and “popular as crime.”

The cops and criminals drawn to Holiday could be hard to tell apart: they fraternized with one another, ganged up against her, and made deals. Her long-time manager Joe Glaser, whether for publicity or as part of a trade-off with the law—he had other drug users to protect among his talent—likely set up Holiday’s 1947 arrest. Another arrest two years later came about when her companion John Levy tipped off the Feds. In 1958 Holiday’s then-husband Louis McKay was caught on tape saying that drug charges against the pair in yet another arrest had already been beat in some kind of back-door exchange involving Holiday, and that since she was no longer an asset to him he wanted to see her in the East River. Her relationship with Black narcotics agent Jimmy Fletcher was friendly, if not the torrid romance the film depicts, and brought advantages to both of them. The point is that the men Holiday sought out as protectors, on either side of the law, helped her when it suited them and turned on her when it didn’t. Holiday’s drug arrests increased her notoriety, and her notoriety increased her value to cops and criminals alike as they maneuvered for their own gain. None of these men, Black or white, appear to have been moved in their actions by the anti-racist lyrics of “Strange Fruit.” They exploited her without regard for what she sang.

(Photo: Billie Holiday courtesy of Getty Images)

Holiday was victimized, but she did not allow her victimization to define her. Federal agent George White told an interviewer it was Holiday’s celebrity that made her interesting to the Feds. But White adds something else. “She flaunted her way of living, with her fancy coats and fancy automobiles, and her jewelry.” Holiday attracted federal attention because she dared to enjoy the fruits of her prodigious talent, to live an abundant life. Andra Day, whose credible performance as Holiday earned her a Golden Globe, hints at what the movie, shorn of its gimmick, might have been: “She’s a Black, queer woman in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, and that—living in that and owning that in itself is defiance.”

This is the Billie Holiday of Dantzig’s photos, of Zadie Smith’s rendering of the singer in “Crazy They Call Me.” Heroin and the law hover just beyond the frame, gnawing at her life’s ragged edges, but what’s central is the artist’s craft—the “landing on an incidental note, a perfect addition, one you never put in that phrase before, and never heard anyone else do, and yet you can hear at once that it is perfection. Perfection!” But “in the end,” Smith’s Holiday says, “people don’t want to hear about” that. They want to know about the betrayals, the arrests, the beatings, the final agony. On this score The United States vs. Billie Holiday delivers.

According to screenwriter Suzan Lori-Parks, Holiday’s associates who betrayed her by tipping off the government “had to give her up like Jesus’ friend gave him up.” The film strains for a light touch with Christian symbolism, to sometimes weird effect. Some twenty minutes into the film we see Holiday weeping in church. Flickering candles surround a casket: someone has died, perhaps Holiday’s mother. The church is unmistakably Catholic. On first watch I’m thinking, things are getting interesting. I wrote a book about Billie Holiday and religion, and I know most biographers won’t go there—won’t wonder at, say, the fact that Holiday spent stretches of her childhood in a convent reformatory, where she sang the Latin chants of the Mass. Or that she never recorded gospel, a staple of the great Afro-Protestant woman singers of the twentieth century. Or that she sings “Strange Fruit” in the manner of Catholic, not Protestant images of crucifixion, the filled cross and not the empty cross, the broken body on the tree, not the gleaming triumph over death.

But Catholicism in this scene turns out to be a sight gag, no more: the funeral is a funeral for a dog. The nod to Holiday’s Catholicism is a head fake, a wink. It tells us that whatever role religion may have played for Billie Holiday, the fraught particulars of her Catholicism will not burden this telling of her life—no more than Harvey Milk’s Judaism, in Krutzsch’s reading, would come to matter for his memorialization as a gay Christ figure. In both cases, the religious formation with less cultural currency (secular Jewishness in Milk’s case, an ambivalent Catholicism in Holiday’s) dissolves in the light of the far more legible and potent Christian imagery of the crucified and resurrected savior.

Of this imagery The United States vs. Billie Holiday gives us plenty. When the cops come for Holiday in her apartment, she strips naked and extends her arms at right angles like the crucified Christ, a cross on the wall repeating the cruciform shape behind her. When Holiday stumbles on a lynching in the woods, the crucified Black body on the tree is a woman’s. Near the end of the film, at the very end of her life, Holiday decides she’s missed her calling: what she should have been singing all along is gospel. This least Black-churched among the century’s great women singers lights into her own rendition of “Can’t No Grave Hold My Body Down,” Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s rousing hymn of death and resurrection.

The point of making people into martyrs, Krutzsch reminds us, is to make martyrs do saving work: to attach unjustly curtailed lives to “the Christian idea that suffering and death can have a purpose, and that, like Christ’s suffering on the cross . . . one’s trials today can lead to a better tomorrow.” (Case in point: the notion that George Floyd “sacrific[ed his] life for justice.”) But, Krutzsch demurs, “there is no guarantee that traumas lead to anything better, individually or collectively.” The United States vs. Billie Holiday wants us to believe otherwise. “If we had listened to Billie Holiday, says Hari, “there would be a lot of Black people who were killed who’d still be alive, a lot of Black people who were imprisoned who would have lived free lives, and a lot of people who died of addictions who would have lived to recover and have good lives. I think it’s time we started really listening to Billie Holiday.”

We are listening. We’ve been listening. No one before Billie Holiday sounded remotely like her, and no jazz musician, no singer in any genre escapes her influence today. No government or other power could stop people from listening to Billie Holiday, then or now. But it will require more than listening to Billie Holiday to do what Hari imagines listening to Billie Holiday will accomplish. Let her provide the inspiration and a soundtrack, without making her life into the saving myth that does the work.

Tracy Fessenden is the Steve and Margaret Forster Professor of Religious Studies at Arizona State University. She is the author of Religion Around Billie Holiday.