Battling our Demons, On Screen and Off

S. Brent Plate on fighting the demonic stereotypes rampant in contemporary media.

The Temptation of St. Anthony by Martin Schöngauer c. 1480-90. Engraving. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In the midst of one shooting after another of unarmed black men by police officers, one comment keeps sticking in my mind: officer Darren Wilson’s expressed fear of Michael Brown before he shot him six times and killed him. Wilson claimed of Brown, “he looked up at me and had the most intense aggressive face. The only way I can describe it, it looks like a demon.”

What does it mean to look “like a demon”? How would Wilson know what a demon looks like? Was he implicitly claiming he’s actually seen a demon? Or was Wilson, most likely, projecting an image of a demon from popular media onto the face of a real person?[1] A monstrous, unreal other overlaid on the face of another, real person? And has media so influenced us that we don’t know the real from the fake and we’re ready to pull the trigger regardless?

Demons are religio-cultural creations, emerging at various points in time and confronting us as our other. They are creatures that look just enough like us to elicit our recognition, but they are disfigured by our fears: white walkers in Game of Thrones; the gigantic, winged Balrog of Morgoth rising from the dark abyss to take down Gandalf in Lord of the Rings; or a creepy doll in Annabelle: Creation. In a nice reversal, and reminding us how quotidian they may be, we see them walking the earth as Matthew McConaughey in The Dark Tower.

These ancient, mythical creatures from the dark depths have tantalized audiences since ancient Assyrians brought Lamashtu to life, Indo-Aryans told stories of Vritra, and Jews wrote of the dreadful Beelzebub. They’ve been devastating and demolishing for millennia.

We love our mediated demons, in word and image, but keeping them on the other side of the screen has proven to be a challenge. The world on screen crashes into the world off screen and we struggle to sort through the differences.

Cognitive and corporeal confusions

Cognitive scientists are increasingly showing how our bodies and minds have evolved in ways that make it difficult to readily differentiate between reality and representation. Screened realities and actual realities swirl in our memories, producing our pasts, our stories, and ultimately, ourselves. Summarizing much of this research, cognitive psychologist Jeffrey Zacks notes “that if you watch a film–even one concerning historical events about which you are informed–your beliefs may be reshaped by ‘facts’ that are not factual.”

Study after study has shown how if we watch historical inaccuracies in films, we are likely to remember them as true, even if we’ve already read about the “truth” of the matter in other places. Films rewrite our memories. They can help us remember history, and thus are useful in pedagogy, yet if the accounts are not “historically accurate” (and I use that term loosely), we will just as likely believe the made-up aspects as we will facts.

Which means: believe what we want, but there is no “real world” separate from the “filmed world.” Instead, as I argue in my recent book, Religion and Film, cinema re-creates the world. There is no pretending that going to the movies is merely an “escape” that has no bearing on the rest of our lives. Instead, the movies, and mass media in general, influence our views of race, religion, gender, sexuality, as well as our understanding of historical fact.

The real and false demons of The Exorcist

We can see similar cognitive confusions in the screened demons of The Exorcist, directed by William Friedkin and based on the best-selling novel by William Peter Blatty. The release of the film, the day after Christmas in 1973, was met by what came to be called “The Exorcist Phenomenon.” People lined up for hours to watch the film, even in freezing January temperatures, and many were so thrilled to be scared they went for second and third viewings.

Meanwhile, inside the theaters a staggering number of people vomited or fainted during the screenings. The deep, raspy voice of the devil coming out of little Regan’s mouth was too much for many, while others lost their senses when her head did a 360. One Los Angeles theater owner estimated that during each screening, a half-dozen people were fainting, vomiting, or quickly running for the exits in his theater.

Screened realities and “real life” were confused, and there were reports across the United States about local priests being called by parishioners who had just seen the film and feared that they too might be possessed by a demon and needed a good dose of psychological and/or theological counselling.

While the general public flocked to the film, critics didn’t have such a warm reception. In her book, Catholics in the Movies, Colleen McDannell takes care to note how Pauline Kael at the New Yorker and Vincent Canby at the New York Times panned the film. The main problem for them was that the demonic possession wasn’t an allegory of something else, in ways that George Romero’s 1968 Night of the Living Dead had been seen as a veiled comment on U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Instead, notes McDannell, “For Kael, Canby, and other reviewers, the film tricked people into thinking that the devil and the world of demonic possession were actually real.”

It was the hyperreality of The Exorcist that allowed it to cross over from the screen and possess the bodies of its audience, making them faint, flee, scream with fright, and send high-brow reviewers into full condemnation mode.

It was the hyperreality of The Exorcist that allowed it to cross over from the screen and possess the bodies of its audience, making them faint, flee, scream with fright, and send high-brow reviewers into full condemnation mode.

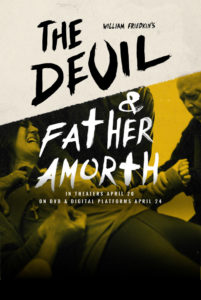

Now, 45 years later, William Friedkin has just released the documentary, The Devil and Father Amorth, the “true story” of the official exorcist of the Diocese of Rome. The trailer introduces us to Father Amorth, saying “this is not fiction. It’s different from all the movies.”

Friedkin shifts from “fake” exorcism–Linda Blair doing 360-head spins–to the “real” exorcism of a woman. As the press release notes, it “is a startling and surprising story of the religion, the ritual and the real-world victims involved in possession and exorcism.”

And yet, the trailer itself borrows from standard horror film audio-visual tricks with eerie sounds, slowly opening doors, and quick takes of writhing bodies. Fiction films have taught us how to see horror, and now we can’t look any other way, even when we’re trying to show the reality of it.

How do we know the difference? Maybe truth and fiction, the world on-screen and the world off-screen, are not so separable, at least within the deep recesses of our bodies.

Re-framing the screen

The reality is, getting rid of fiction–and images of fictional creatures such as demons–is not an option. Indeed, fiction is critical to human’s evolutionary history.

Yet, in many circumstances, it is essential that we figure out “what really happened,” and so lawyers, juries, and historians work to sift through evidence that points toward something of the previous reality. As any good judge and journalist will admit, the past is always a reconstruction, just as justice demands a truthful reconstruction.

One response is to use education to help separate the facts of history from the fictions. Those studies noted above that tell of the fact-fiction blurring in the classroom also suggest that, given proper warnings, students can remember the correct information, at least much of the time.

And while our cognitive systems don’t treat presentation and re-presentation differently, we can relearn our visual patterns, changing our neural pathways. I’ve argued elsewhere that changing the images on screen can influence the ways we see people off screen, including our racial and racist preconceptions of others.

Writing in The Corporeal Image, documentary filmmaker David MacDougall makes a case for the power of films, saying that they “allow us to go beyond culturally prescribed limits and glimpse the possibility of being more than we are. They stretch the boundaries of our consciousness and create affinities with bodies other than our own.” MacDougall is talking here about a range of films, not only documentaries.

And so, we need better movies, even if they are about demons. Even if they are fiction. Even if they are not real. Because they change the ways we see in the so-called “real world.”

Fighting our demons means, among other things, fighting against racist, sexist, ageist, Islamophobic, and homophobic stereotypes, among others. These are rampant across contemporary audio-visual media. We’ll always confuse what’s on screen with what’s off-screen. But by pointing toward better representations, and producing better representations, on-screen, we begin to change the ways we see off-screen, offering “affinities with bodies other than our own” and perhaps making the face of the other less demon-like.

***

[1] There is, of course, a crucial question of how racism operates here, and how these images become racialized. I’ve written about race and images elsewhere recently at The Conversation. See also Maryam Monalisa Gharavi’s “Transcript of a Face.”

***

S. Brent Rodriguez-Plate, PhD, is a writer, public speaker, editor, and part time college professor whose books include A History of Religion in 5 1/2 Objects, Blasphemy: Art that Offends, and Religion and Film: Cinema and the Re-Creation of the World. His essays have been appeared at Salon, Newsweek, The Christian Century, The Islamic Monthly, Huffington Post, Religion Dispatches, and elsewhere. He is a board member of the Interfaith Coalition of Greater Utica, NY, and President of the Association for Religion and Intellectual Life/ CrossCurrents. He lives in Central New York with his family, and holds a visiting appointment at Hamilton College, NY.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.