America's Most Famous Catholic (According to Himself): Stephen Colbert and American Religion in the Twenty-First Century

A book excerpt with an introduction by the author

America’s Most Famous Catholic (According to Himself): Stephen Colbert and American Religion in the Twenty-First Century examines how Catholicism shaped Stephen Colbert’s life, as well as how he influenced American Catholicism through his celebrity status and television character. From 2005 to 2014, Colbert played a devout, vocal, and authoritative lay Catholic on The Colbert Report. Dubbed “Colbert the Catechist” by religion blogs, religion is central to both the actor and his most famous character. The juxtaposition between Colbert’s status as a celebrity Catholic and as a comedic critic of the Catholic Church lies at the heart of this book. What sets Colbert apart from other comedians is that he approaches religious material not as an irreverent secular comedian, but as one of the faithful.

This excerpt comes from the book’s first chapter.

***

Chapter 1: Colbert as Character

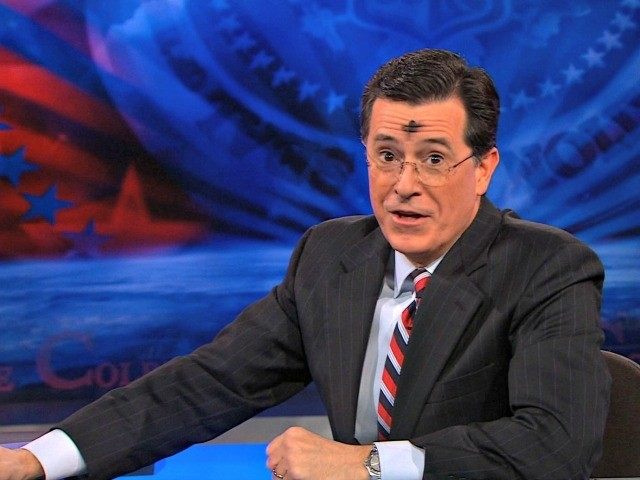

Two hundred excited people fill the waiting area at The Colbert Report studio on November 18, 2014. Small bursts of laughter fill the crowded room as two large flat screens adorning the walls play segments from the Comedy Central program on repeat: a two-minute clip about Wheat Thins crackers, the Daft Punk band playing a set on the studio stage, The Colbert Report in Afghanistan and Iraq performing for U.S. troops. The walls are painted in red, white, and blue as the crowd gathers in anticipation around the entrance to the studio. The studio doors open, and the crowd rapidly moves to fill in available seats in the theater. A half-hour before the evening’s taping, Stephen Colbert enters the room to raucous applause. Wearing a dark suit, the actor (not the character) addresses the audience: “Anyone have any questions for me?”

Just a few hours before, I had been standing in line, waiting with hundreds of others to enter the studio. I had interviewed other audience members, asking them where they were from, what they thought of Colbert, and personal questions about their religious and political identities. As I raise my hand eagerly in response to Colbert, those seated around me (whom I had recently interviewed) quickly interject. “Ask her,” a few audience members exclaim while pointing at me. “She’s researching you.” Bemused, Colbert acknowledges my raised hand.

“Why did you choose for your character to be Catholic?” Colbert smiles at this question, an amused grin as though he had not encountered this question as part of his regular routine. How often do audience members reference his religious identity? I am not his usual fan.

“Why did you choose for your character to be Catholic?” Colbert smiles at this question, an amused grin as though he had not encountered this question as part of his regular routine. How often do audience members reference his religious identity? I am not his usual fan.

Colbert gives a three-part response. First, he replies that when he started The Colbert Report, he was given some advice. “Johnny Carson told David Letterman who told Conan [O’Brien] who told me, doing a show this much, four days a week, is going to take everything you know. And I know a lot about being Catholic.” A few gasps of recognition betray that the lineage of this advice impressed me and some of my fellow audience members. In the second part of his response, Colbert emphasized that he knew he could “play up the liberal/conservative” divide evident in American Catholicism. He could take on an exaggerated conservative persona to become “Captain Catholicism.” As Colbert strikes a superhero pose, audience members chuckle. In the third part of his response, Colbert pauses and steps back, away from the audience. He stares off, almost in amazement of his situation, and laughed, “I mean, it’s pretty neat. I get to interview priests. It’s pretty fun.”

***

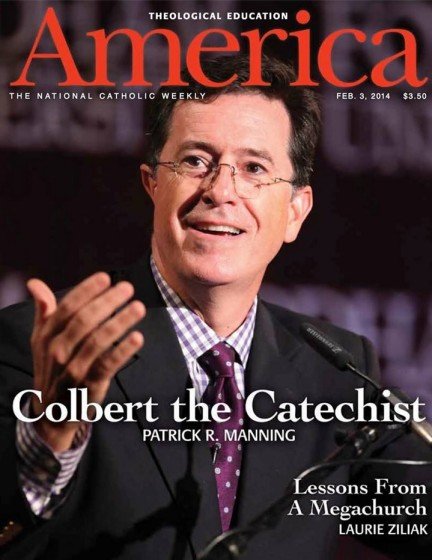

With its debut in 2005, The Colbert Report cast the actor Stephen Colbert as the boisterous satirical character STEPHEN COLBERT. Two personae, but one name and one body. To distinguish the two in text, I use Colbert for the actor and COLBERT in caps for the character (while it seems like shouting, all caps is appropriate, as yelling is one of COLBERT’S exaggerated traits). Both the actor and character are devout, vocal, and authoritative Catholics. Colbert’s exaggeration of COLBERT’S position and power led COLBERT to proclaim that he was “television’s foremost Catholic.” His religion was so central to the show that religion blogs dubbed him “Colbert the Catechist.” The Jesuit magazine America even went so far as to recommend Catholic educators take notes on his entertaining and persuasive evangelizing style. As The Colbert Report ended its series run in late 2014, The National Catholic Reporter named Stephen Colbert their “Runner-up to Person of the Year,” second only to Pope Francis. For the editors and readers of the progressive Reporter, Stephen Colbert represents a powerful mouthpiece for their political, social, and religious perspectives. And yet, the question I am asked most often is, “Colbert’s really a practicing Catholic? In real life?” That juxtaposition between Colbert’s revered status as a celebrity Catholic and as a polemical satirist of institutions lies at the heart of America’s Most Famous Catholic (According to Himself).

Stephen Colbert stands in a historical lineage of public Catholics who have navigated the shifting tides of American Catholic authority. As Colbert joked during his keynote address at the 68th annual Alfred E. Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner (a dinner honoring the first Catholic nominee for the American presidency), on October 17, 2013, “I am proud to be America’s most famous Catholic.” With this bold statement in a room full of cardinals, priests, politicians, actors, and other Catholic celebrities, Colbert references both his intense popularity and his embodiment of both American and Catholic identities. He is the latest incarnation of Catholic religious celebrities and mass-mediated broadcasters in the United States.

Stephen Colbert stands in a historical lineage of public Catholics who have navigated the shifting tides of American Catholic authority. As Colbert joked during his keynote address at the 68th annual Alfred E. Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner (a dinner honoring the first Catholic nominee for the American presidency), on October 17, 2013, “I am proud to be America’s most famous Catholic.” With this bold statement in a room full of cardinals, priests, politicians, actors, and other Catholic celebrities, Colbert references both his intense popularity and his embodiment of both American and Catholic identities. He is the latest incarnation of Catholic religious celebrities and mass-mediated broadcasters in the United States.

Colbert presents a version of American Catholicism, but not the sole version. Colbert illustrates and embodies certain complexities of Catholic identity and relationships between Catholic lay and institutional authority both in his individual presentation of his Catholic identity and through the complicated endeavor of being both a celebrity and a character inhabiting the same body with the same name. While there are multiple sides of Colbert, that does not mean he represents all of the complexity in contemporary American Catholicism. Instead, Colbert’s racial and ethnic status as a middle-aged white man mirrors that of other dominant images of Catholic representation. In mass media, as in other public arenas, Catholicism, and particularly Catholic authority, is often depicted as white and male, especially in the fields of entertainment, television, and comedy.

Colbert uses satire and humor to question hypocrisies and incongruities that he sees in the Roman Catholic Church. He is a Catholic celebrity who can bridge between critical outsider and participating insider. The persona he cultivates employs satire and critical humor to navigate what it means to be an American Catholic and the relationship between lay and institutional authority. Some viewers describe this as “Colbert Catholic[ism].” Colbert Catholicism complicates the existing literature about “cafeteria,” “cultural,” and “thinking” Catholics, the liberal and conservative Catholic divide, and the trajectory of twentieth- and twenty-first-century changes in Catholic authority.

Through the persona COLBERT, Colbert explores the paradox of Catholic multiplicity. He can do so as a lay person in ways that many mediated and televised Catholic clergy have been unable to do. Colbert speaks for, with, and to an audience grappling with seeing Catholicism as multifaceted. Colbert’s Catholicism creates this contemporary paradox of being religious while also mocking certain aspects of religion primarily because Catholicism is often defined with and against the institution of the Catholic Church. There is a perception of a right answer, a real way of being religious. While that perception is false and there are millions of ways in which to be Catholic in the contemporary world, the perceptions and assumptions remain. To be Catholic is to constantly define and redefine oneself with and against the perception of a unified, authoritative, and institutional Church.

Through the persona COLBERT, Colbert explores the paradox of Catholic multiplicity. He can do so as a lay person in ways that many mediated and televised Catholic clergy have been unable to do. Colbert speaks for, with, and to an audience grappling with seeing Catholicism as multifaceted. Colbert’s Catholicism creates this contemporary paradox of being religious while also mocking certain aspects of religion primarily because Catholicism is often defined with and against the institution of the Catholic Church. There is a perception of a right answer, a real way of being religious. While that perception is false and there are millions of ways in which to be Catholic in the contemporary world, the perceptions and assumptions remain. To be Catholic is to constantly define and redefine oneself with and against the perception of a unified, authoritative, and institutional Church.

America’s Most Famous Catholic (According to Himself) investigates the ways in which Colbert challenges perceptions of Catholicism and Catholic mores through his comedy. Through his television program and digital media presence, Colbert is a twenty-first-century celebrity pundit who inhabits a realm of extreme political and social polarization. I examine how Catholicism shapes Colbert’s life and world, and also how he and his persona influence Catholicism and American Catholic thought and practice. In addition, I analyze how Colbert and his character COLBERT nuance the polarized religious landscape, making space for Americans who currently define their religious lives through absence, ambivalence, and alternatives. Colbert and COLBERT reflect the complexity of contemporary American Catholicism as it is lived, both on- and off-screen.

Religion and the foibles of religious institutions have served as fodder for a number of comedians. In this, Colbert is not unique. What sets Colbert apart is that his critical observations are harder to ignore because he approaches religious material not from the predictable stance of the irreverent secular comedian but from his position as one of the faithful. He uses humor to engage in significant public criticism of religious institutions, policies, and doctrines. In the satirical tradition of Jonathan Swift and Mark Twain, COLBERT informs audiences on current events, politics, social issues, and religion while lampooning conservative political policy, biblical literalism, and religious hypocrisy. Stephen Colbert and his character dwell at the crossroads of religion and humor. This book is a case study of that intersection: humor as an arena for the expression of religious identities and relationships. Comedy becomes a site for critique and dialogue between lay religious practitioners and their larger institutional authoritative bodies. Religious worlds are not solely serious, and individuals, in particular comedians, negotiate their relationship to aspects of religion with humor.

Stephanie N. Brehm is an administrator-scholar at Northwestern University working in the Graduate School on academic and strategic initiatives. She is a faculty instructor in Northwestern’s Master of Science in Higher Education Administration and Policy program. She earned her Ph.D. in Religious Studies at Northwestern in 2017 where she specialized in American Religious History and Media/Popular Culture.