American Trinity: Faith, Fame, and Fanaticism

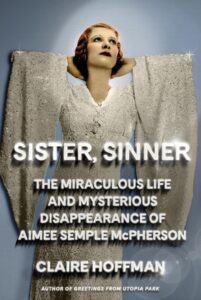

A review of "Sister, Sinner: The Miraculous Life and Mysterious Disappearance of Aimee Semple McPherson"

(Aimee Semple McPherson preaching. Image source: Bettman/Getty Images/Vanity Fair)

Long before televangelists and celebrity influencers came along, Aimee Semple McPherson built a religious media empire on charisma, spectacle, and relentless self-promotion in the 1920s, commanding a near cultic-following and making her one of the most famous—and polarizing—figures of the early twentieth century. Yet at the end of her page-turning recent biography of the scandal-ridden evangelist, Claire Hoffman surprisingly observes that McPherson seemed all but forgotten at the hundredth anniversary celebration of the church she founded, Los Angeles’ Angelus Temple. Erected by McPherson in LA’s Echo Park neighborhood in 1923, the colossal building, with seating for more than 5,000 people, was one of the largest churches ever constructed at the time, the first model for the many cavernous megachurches that would sprout up around southern California and all over the country in the ensuing decades. An active congregation to this day, the Angelus Temple also serves as the headquarters for the Foursquare Church, the Pentecostal denomination McPherson created that now counts more than 8 million members. But as Hoffman notes, the centennial event paid little homage to McPherson other than some cursory nods to her legacy, even as one speaker told the crowd, “It is good to remember the past for all that we can do in the future.”

Hoffman’s terrific book, Sister, Sinner: The Miraculous Life and Mysterious Disappearance of Aimee Semple McPherson, does that remembering in fine detail. Her thorough and intriguing account of McPherson—the most famous woman preacher to ever take the pulpit and one of the most important influences on twentieth-century American evangelicalism—charts a path that many American celebrities have navigated: from humble obscurity to worldwide recognition, then from scandal to greater public notoriety and even personal redemption.

Hoffman’s terrific book, Sister, Sinner: The Miraculous Life and Mysterious Disappearance of Aimee Semple McPherson, does that remembering in fine detail. Her thorough and intriguing account of McPherson—the most famous woman preacher to ever take the pulpit and one of the most important influences on twentieth-century American evangelicalism—charts a path that many American celebrities have navigated: from humble obscurity to worldwide recognition, then from scandal to greater public notoriety and even personal redemption.

Hoffman is well-suited to guide readers through that transformation. A journalist who has profiled the likes of Amy Winehouse, Justin Bieber, and Michael Jackson, Hoffman understands how fame can damage and destroy the lives of those who achieve it. And Sister Aimee—as McPherson’s devotees called her—provides Hoffman, who also has a graduate degree in religion, an opportunity to explore how religious faith can heighten both fame’s privileges and its punishments.

In McPherson’s case, her religious reputation compounded the otherworldly aura that fame already bestows on the favored few, rendering her not merely a star, but something more—a divine oracle, one of God’s chosen messengers on earth. On the other hand, when she faced scandal, her fall from grace provoked even more righteous condemnation and moral judgment—at least from her critics—than what the average humiliated public figure must endure. Although she managed to vanquish her foes and enlarge her following, McPherson grew increasingly paranoid and isolated, ultimately perishing from an accidental overdose of sedatives at the age of 53. Hoffman concludes that McPherson’s life offers “a cautionary tale about fame. About how poisonous the gaze of the public eye can be for those who live their lives in front of it.”

Yet the real lesson of Sister, Sinner may not be in what it shows us about how fame encages the individual, but rather how it traps all those who sit under its spell. How fandom can easily become fanaticism. And how fervid adoration, unquestioning devotion, and blind loyalty alter the faithful, distorting their desires, twisting their values, and deforming their reality—and often the world for all those around them.

***

Born in 1890 in a small town in Ontario, Canada, the young Aimee grew up in a deeply religious home. Her mother, Minnie, had dreamed of a life devoted to her beloved Salvation Army. Married at fifteen and pregnant at nineteen, Minnie didn’t so much abandon that calling as transfer it to her daughter. Only weeks after giving birth, Minnie made a harrowing trek through the frigid woods to place her new baby on her church’s altar and dedicate Aimee “fully for the Salvation of the world.”

The teenage Aimee, “pretty and popular,” had other ideas until, almost as a joke, she asked her father to take her to a Pentecostal revival happening in town. Aimee wanted to laugh at the “Holy Rollers” speaking in tongues and collapsing to the floor in wild gyrations as the Holy Spirit took hold of them. Instead, Aimee was converted.

Although Pentecostalism had barely been around a few years when the seventeen-year-old Aimee felt its pull, the burgeoning faith, with its emphasis on ecstatic worship and personal sanctification via physical experiences like speaking in tongues, was growing steadily thanks to the traveling evangelists who spread its message throughout North America. Aimee was soon one of them. Unlike more established denominations, female evangelists were rather common in early Pentecostalism where leaders believed they needed all possible preachers to build the young faith. After stints preaching on the crowded streets of New York and the flat fields of Florida, McPherson, with her mother Minnie in tow, arrived in Los Angeles in 1918, having ditched along the way her second husband, Harold McPherson, when he tried to make his own name at preaching. (The couple divorced three years later.)

In a city made for stars, McPherson quickly shone the brightest. As the birthplace of Pentecostalism, and the fastest growing city in the world at the time, Los Angeles made an ideal place for McPherson to make her mark. In short time, McPherson had amassed a large following, preaching across the city and reaching others through her constant travels on the revival circuit. McPherson enchanted her audiences through her emotional intensity, spiritual fervor, and direct and simple language that everyone could understand. Her optimistic message and promise of healing, both spiritual and physical, had special appeal for the thousands raptured by her preaching. Beyond Los Angeles, McPherson harnessed the existing media technologies of the era to connect with even more Americans, publishing her own religious magazine and making herself available to reporters from LA’s two competing newspapers who knew that any story about Sister Aimee would cause a spike in sales. Her radio shows broadcast on her own station—McPherson was the first woman granted a radio license in the U.S.—introduced her to an even bigger audience.

The sprawling Angelus Temple provided McPherson with her best stage, a platform to showcase her rhetorical talents and theatrical flair. What McPherson developed for her worship services would be copied by many a non-denominational megachurch over a half century later: smoke machines and moody lighting, elaborate costumes and intricate scenery, and dramatic pageants with live animals. “In this show-devouring city,” one journalist wrote after a visit, “no entertainment compares in popularity with that of Angelus Temple.” When her four sermons a week couldn’t satisfy the demand, McPherson ordered the temple’s doors remain permanently open and scheduled religious programming for every day of the week.

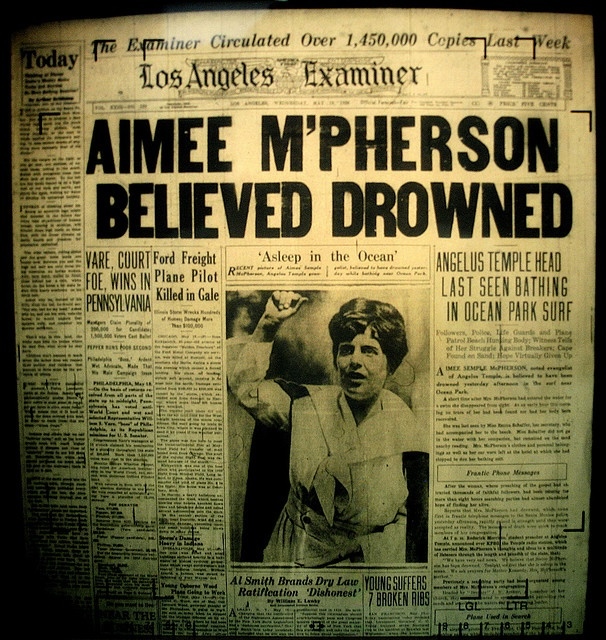

Perhaps the pressure proved too much. Or maybe she wanted to attract more adherents. In any event, on a late spring day in 1926, McPherson walked out of the Angelus Temple past a throng of her fans and headed to Venice Beach where she frequently swam in the cold ocean. Dressed in an emerald-green bathing suit and cap, McPherson slipped into the water and disappeared. The thousands who soon packed the beach to hold vigil for McPherson represented just a sliver of the many who were captivated by her vanishing, to say nothing of the millions more who would be mesmerized by her sudden reappearance. A little over a month later, McPherson emerged from the Mexican desert just south of Douglas, Arizona, claiming to have escaped from kidnappers from LA’s underworld who wanted to stop her anti-vice campaign in the city.

The story—covered religiously on the front page of nearly every newspaper in the country—quickly fell apart as both journalists and LA’s law enforcement investigated the evidence. McPherson’s supposed abduction, it seemed clear, had really been devised to cover up an affair, carried out in a “love shack” in northern California. But it was no matter. The tawdry scandal conferred on McPherson what even her religious renown had not, making her a household name almost overnight. As McPherson proudly boasted, she was now “the most famous woman in the world.”

(Image source: The Gospel Coalition)

Hoffman is fascinated by that fame and how it directs and distorts the rest of McPherson’s life. McPherson dabbles in show business and is rumored to undergo multiple surgeries, consumed by how she looks in all the media coverage. She launches multiple harebrained business ventures to extract even more money from her supporters than the offering plates can collect: hotels, housing developments, cruise lines, and a cemetery. The grifter types who often come along with such schemes become her inner circle; those who had assisted her rise turn into her enemies. A flurry of lawsuits makes her a frequent fixture at the Los Angeles courthouse.

Hoffman doesn’t situate McPherson in a broader history nor does she make a case for why her story matters today. (For that, there are several fine biographies that already exist, most recently the historian Matthew Avery Sutton’s excellent 2007 book, Aimee Semple McPherson and the Resurrection of Christian America). Yet readers might recognize the elements of McPherson’s life replicated in the lives of other religious hucksters across the twentieth century—and in our current political moment.

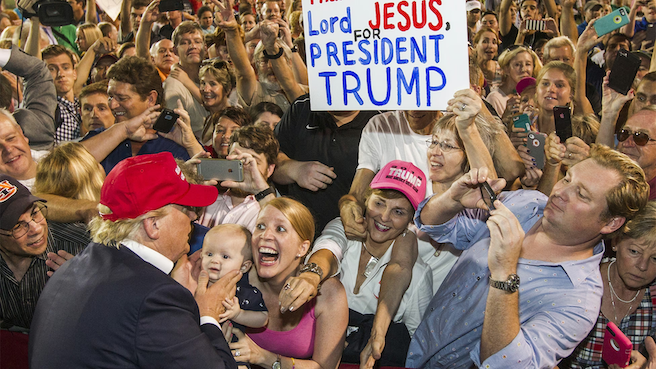

Donald Trump’s name never appears in Sister, Sinner. But it’s hard not to read Hoffman’s account of McPherson without drawing parallels to the president—and especially to the powerful hold he has on his unshakeable backers. When investigators scrutinized McPherson’s kidnapping tale, she lashed back that she was being persecuted for her righteousness, a plot by Satan to destroy God’s elect. Of course, she hastened to add, this wasn’t a swipe just at her, but actually an assault on all the good people she represented. Conjuring a dark and dangerous world animated by the evil forces who controlled the government and media, McPherson made her legal battle a symbol of their oppression. “We are under the persecution of certain interests bent upon our destruction,” she proclaimed, “and they would stop at nothing to put us out of the way.” But she would be their martyr. “I am like a lamb led to the slaughter,” she told her loyal watchers, quoting from the Book of Isaiah, as she entered the courtroom.

Aided by a news industry obsessed with her every move, McPherson turned the media’s harsh glare into a beaming spotlight. Combining the allures of celebrity with the moral indignation of American fundamentalism, McPherson concocted an intoxicating brew that kept her followers enthralled and committed to her cause. Within months of her scandal breaking and the legal case against her beginning, McPherson’s congregation doubled in size. The audiences that met her there and wherever she went became all the more zealous in their enthusiasm for McPherson, and she knew it. “There is absolutely nothing which I wanted that my followers would not gladly give me,” she remarked. “I can ask anything and get it.”

Such words seem an eerie forerunner to Trump’s 2016 brag that he could “stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and I wouldn’t lose any voters,” perhaps the truest thing he has ever said. Both he and McPherson built their power, in part, through a narrative of persecution where they and their followers were under attack by sinister, shadowy elites. That outsized sense of being persecuted doesn’t just elicit unwavering allegiance. It also makes true believers dismiss any inconvenient or incriminating evidence against their idol as the very proof of the larger conspiracy against themselves and their way of life. In such a relationship, devotion always trumps doubt because the truth would be a betrayal.

(Image source: Mark Wallheiser/Getty/The Atlantic)

Ultimately, what McPherson and Trump reveal is less about their own charisma than about the emotional needs of those who follow them—and the societal consequences of that twisted psychology in a country where a potent mix of faith, grievance, and identity overtakes so many.

The famous will come and go. The pathologies unleashed by their rabid fandoms, however, stay with us much longer.

Neil J. Young is a historian and author in Los Angeles. His most recent book is Coming Out Republican: A History of the Gay Right.