American Border Religion

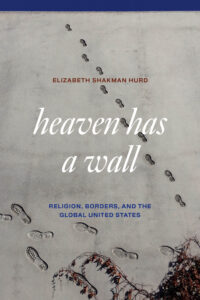

An excerpt from "Heaven Has a Wall: Religion, Borders, and the Global United States"

(Image source: Evan Rosa/Yale Center for Faith and Culture)

The following excerpt comes from Elizabeth Shakman Hurd’s Heaven Has a Wall: Religion, Borders, and the Global United States (University of Chicago Press, 2025). The book explores how American national borders, and our conversations about them, function in religious ways.

This excerpt comes from the book’s introduction.

***

US borders offer up a paradox. They have a capacity to be both present and absent. They are avowed and deferred. Open and closed. They are a “substantial yet porous object” whose “boundaries are clear yet also open.” The US is defined simultaneously by ferocious bordering practices and a willingness to defy borders in the name of something greater than itself. This paradox cannot be explained away by material interests. The experience of the border speaks to something more: it is a site of retrenchment and transcendence. It involves erasure and enforcement. It demands the suspension of the law as well as its vigorous prosecution. At the heart of this paradox is the conviction that borders must be rigorously defended even as America is celebrated as borderless and all encompassing. Borders are technocratic fantasies and places of extreme violence. They are efforts to escape the ordinary. They exist within and beyond the law. “In contrast to the emphasis on a historic homeland that would define European nations,” writes historian Rachel St. John, “Americans embraced the notion that their national boundaries would continue to expand to incorporate ever more land and people under the umbrella of republican government.” Philosopher Jean Baudrillard describes this expansionist tendency as a “hyperreality”: “America is neither dream nor reality. It is a hyperreality. It is a hyperreality because it is a utopia which has behaved from the very beginning as though it were already achieved.”

The border paradox resists resolution even as it incessantly demands it. News from the border drives the news cycle and floods the airwaves. Discussions echo through American courtrooms, classrooms, and congressional hearing rooms. Border law and policy motivate protests and grassroot movements, from private paramilitary groups like the Minutemen to legal reform advocates and those calling for borders to be abolished. Civil, immigrant, and Indigenous rights’ advocates file lawsuits and raise funds. Nationalists organize border patrols and argue with humanitarian activists in the desert. Advocacy groups are stretched to the limit as US borders are transformed into sites of humanitarian and natural disaster. Experts invoke border enforcement in discussions of defense and security, built infrastructure and biometric technologies, and humanitarian and climate crises. Religious groups spearhead humanitarian relief, harkening back to the Sanctuary movement of the 1980s. Academic and policy discussions of refugees, migration, and religion are flourishing. Scholars debate the finer points of border history; one prominent historian describes the wall as a monument to the final closing of the American frontier. Though some contend that US territorial expansion has seen its day, others see America’s boundless frontier manifesting in new ways: in the US commitment to technological innovation over territorial expansion and in American efforts to innovate our way out of the climate crisis.

Despite the flurry of attention surrounding US borders, few have considered borders as sites not only of regulation, violence, and control but also of redemption, enchantment, boundless expansion, and salvation. These are religious as well as political concepts.

There is something sacred about borders. They are religious in Kathryn Lofton’s sense of “enshrining certain commitments stronger than almost any other acts of social participation.” As Lofton explains, “religion isn’t only something you volunteer to join, open-hearted and confessing. It is not only something you inherit, enjoined by your parents. Religion is also the thing into which you become ensnared despite yourself.” Borders are religious in the sense that they reckon with human limits. They are sites at which the limits of the human become apparent. They are religious in the sense of having a capacity to summon a sacred American nation without necessarily summoning “religion.” To enter into the religiosity of borders conceived in this way it is helpful to start with material and other exchanges that are not usually considered problematic: tomatoes, tourists, butterflies, and so on. The “religious,” we quickly find, is not the only place we find the sacred. The sacred is expressed in ways that exceed the logics of the modern construct of religion. It has been captured in notions such as the mysterium tremendum et fascinosum (mystery that repels and attracts), the homo sacer (in Roman law, he who is banned but cannot be sacrificed), and all that which is honored through borders, such as clean/dirty, permitted/taboo, and sacred/profane. It is in objects too, as Mateo Taussig-Rubbo finds in property recovered from the rubble of 9/11.

There is something sacred about borders. They are religious in Kathryn Lofton’s sense of “enshrining certain commitments stronger than almost any other acts of social participation.” As Lofton explains, “religion isn’t only something you volunteer to join, open-hearted and confessing. It is not only something you inherit, enjoined by your parents. Religion is also the thing into which you become ensnared despite yourself.” Borders are religious in the sense that they reckon with human limits. They are sites at which the limits of the human become apparent. They are religious in the sense of having a capacity to summon a sacred American nation without necessarily summoning “religion.” To enter into the religiosity of borders conceived in this way it is helpful to start with material and other exchanges that are not usually considered problematic: tomatoes, tourists, butterflies, and so on. The “religious,” we quickly find, is not the only place we find the sacred. The sacred is expressed in ways that exceed the logics of the modern construct of religion. It has been captured in notions such as the mysterium tremendum et fascinosum (mystery that repels and attracts), the homo sacer (in Roman law, he who is banned but cannot be sacrificed), and all that which is honored through borders, such as clean/dirty, permitted/taboo, and sacred/profane. It is in objects too, as Mateo Taussig-Rubbo finds in property recovered from the rubble of 9/11.

The slipperiness of borders shapes some of the most urgent political developments of our time. The border’s capacity to be simultaneously fluid and firm, present and absent, lawful and lawless, sacred and secular disrupts social scientific and governmental efforts to describe, delineate, and control border spaces. The border paradox manifests in the politics of race, immigration, asylum, foreign policy, and national security. It shapes the adjudication of asylum. It authorizes national security to operate simultaneously within and beyond the reach of the law. It buoys US support for the State of Israel in ways that have yet to be fully understood. It enables the off-site detention of “enemy combatants.” It energizes stand-offs and sparks fear among US law enforcement as they face down countersovereigns who refuse American borders of all kinds. It traverses presidential administrations and confounds partisan divides, galvanizing unlikely alliances between liberals and conservatives.

That the border is a zone of legal exception is not a new insight. Rachel St. John notes that as early as the 1920s the border had become a “complicated system of relational space” that “could either be fluid or firm.” In her history of the INS, the predecessor to the US Citizenship and Immigration Service, ICE, and CBP, S. Deborah Kang describes the border as “an impermeable sovereign boundary, a permeable socioeconomic zone, and a vast policing jurisdiction.” Because the INS was exempt from the Administrative Procedures Act (APA) of 1946, Kang notes, the agency was “unconstrained by the procedures stipulated by the APA and judicial review of its administration practices and internal adjudication,” thus becoming “an ‘outlaw’ in American legal culture.” In his autobiographical account, former Border Patrol agent Francisco Cantú describes the US-Mexico border as “a vast zone of exception, a place where laws and rights are applied differently than in any other part of the nation.” The one-hundred-mile aforementioned “Constitution-free” border jurisdiction zone includes roughly one-third of the United States and nearly two-thirds of its population. It includes the entire state of Michigan, which has had the fastest rate of growth of any Border Patrol Sector in the country. The number of agents in Border Patrol’s Detroit Sector grew from 35 agents in 2000 to 404 agents in 2019, a 1,054 percent increase. The ACLU explains:

“The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects Americans from random and arbitrary stops and searches. According to the government, however, these basic constitutional principles do not apply fully at our borders. For example, at border crossings (also called ‘ports of entry’), federal authorities do not need a warrant or even suspicion of wrongdoing to justify conducting what courts have called a ‘routine search,’ such as searching luggage or a vehicle. Even in places far removed from the border, deep into the interior of the country, immigration officials enjoy broad—though not limitless—powers. Specifically, federal regulations give U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) authority to operate within 100 miles of any U.S. ‘external boundary.’”

The exceptions continue. DHS considers itself exempt from the Fourth Amendment, and the government has exempted both CBP and DHS from restrictions on racial profiling that are imposed on other federal departments. One DHS official explained, “We can’t do our job without taking ethnicity into account,” prompting the New York Times to report that “department officials argued that it was impractical to ignore ethnicity when it came to border enforcement.” The organization People Helping People documented a pattern of profiling people of color at Border Patrol interior checkpoints, invoking a long history of white supremacy in the patrol. Founded in 1924 as part of the Immigration Act, the patrol in those days, as described by historian Greg Grandin, was “a frontline instrument of white supremacist power” and “a vanguard of race vigilantism.”

US borders are about more than making laws, building barriers, and rationally managing flows of goods and people. Borders involve reaching beyond the collective self, transcending constraints in the search for an American utopia. Borders are also liminal spaces and places. The act of crossing them is imbued with magic and fear. Walls, lines, doorways, and arches are dangerous places to be human. Should one look backward? To whom should one give one’s real name? Can one go back after crossing? The title of this book, Heaven Has a Wall, alludes to the idea that borders are religious as well as political objects. Moving beyond a conventional focus on religious traditions, practices, and beliefs and their influence on collective life, I turn to border history, national security, and immigration politics and foreign policy. Religion is embedded in the matrices of all these phenomena. It cannot be set apart as a distinct object. At the same time, and even as I question fixed boundaries between religion and politics, sacred and secular, and theory and theology, this book is not only for scholars of religion and politics. It is for anyone interested in borders and in the American national project. I especially want to speak to readers who see their own ways of life as less dogmatically religious than others and as therefore promising more inclusive forms of politics and public life. This is common among liberal academics. Religion, they say, is something to be kept in its place, out of politics and public life. If only those to the political and religious right would outgrow their dogmatic expressions of religiosity and the distorted forms of politics they engender, it is said, the US would regain its naturally emancipatory and progressive bearings.

I propose an alternative. US (religious) politics, including border politics, are neither private nor the exclusive domain of political or religious conservatives. Modernity is not a post-religious achievement. The oft-presumed dichotomy between secular modernity and its theological past is a false one. In Eric Santner’s words, “there is more political theology in everyday life than we might have ever thought.” The political is an already-religious space that need not be feared or overcome but understood.

Elizabeth Shakman Hurd is professor of political science and religious studies at Northwestern University. Her books include Beyond Religious Freedom: The New Global Politics of Religion and Politics of Religious Freedom.

***

Interested in more on this topic? Check out episode 59 of the Revealer podcast: “Borders, Immigration, and Religion.”