All Aboard the Orphan Train!

How the U.S. adoption industry contributes to white Christian nationalism

(Image source: Shutterstock)

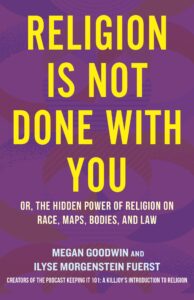

We wrote our new book, Religion Is Not Done With You, with the express intention of helping readers learn to identify and understand how religion shapes the world around us—even (maybe especially) when many of us are not religious ourselves. The book offers a number of examples to show religion at work in the world: shaping maps, calendars, laws, healthcare, even airports! The point isn’t just to show that individual people use religion to do some truly horrific and also spectacularly wonderful things—though that is certainly true—but to encourage more folks to pay attention to systems, particularly systems forged out of white Christian nationalism, that toxic blend of white supremacy, Christian supersessionism, and American exceptionalism.

Religion is easier to spot in some systems than others. It’s hard to miss religion shaping the U.S. Supreme Court, for example, when six of nine justices are Catholic. But what about systems in which the workings of white Christian nationalism are harder to spot—systems we often assume are doing good, kind, and important work? What about, for instance, adoption?

Religion is easier to spot in some systems than others. It’s hard to miss religion shaping the U.S. Supreme Court, for example, when six of nine justices are Catholic. But what about systems in which the workings of white Christian nationalism are harder to spot—systems we often assume are doing good, kind, and important work? What about, for instance, adoption?

Adoption, especially but not exclusively in the United States, is a system that works to support and expand a white Christian nationalist agenda. Of course, this is not all adoption is! In many cases, adoption allows children who need care to find loving homes; adoption can expand families for folks unable to conceive. And let’s get something straight before we go any further: we are not anti-adoption. This issue is both professional (we are scholars of race, power, and religious minoritization) and personal (Ilyse is an adoptee; Megan’s older brother is an adoptee). But, as we’ve explored this season on our podcast, to understand the full picture of adoption, we must account for its white Christian nationalist roots, goals, and operations.

Understanding Adoption

Before we can dive into how adoption has worked and is still working to make more white Christian Americans and keep America a predominantly white Christian nation, we need to go over the basics.

Adoption transfers the legal guardianship of a child, usually but not exclusively from a legally recognized biological parent to another adult. This includes stepparent adoptions, foster care adoptions, private adoptions, and international adoptions. Americans adopt roughly 150,000 children each year; recent figures estimate there are 5-7 million adoptees currently living in the U.S. Adoption is also an industry: IBIS World estimates that the Adoption & Child Welfare Services industry netted $25.2 billion in 2023 alone.

Estimating how much gets spent on adoption is easier than estimating the number of adoptees, however. Most U.S. adoptions (and many adoptions around the globe) are plenary adoptions, which legally and permanently sever ties between biological parents and adoptees to such an extent that adoptive parents are listed on an adoptee’s birth certificate, making it difficult if not impossible to provide an accurate reckoning. Adoptees have vociferously criticized the plenary adoption model, the effects of which irrevocably shape the course of their entire lives.

“Adoptee” might be an unfamiliar term, but it’s an important one: it signals a shift away from focusing on the process itself as something that happens to a person who lacks agency (adoption/adopted) and toward centering the agency of the vulnerable person most affected by the process (the adoptee). Historically, the narrative of adoption privileges the adoptive parents, assuming children cannot fully understand their own experiences, should and will adapt to their new circumstances, and will be grateful they’re receiving care at all

Adoptees who share their experiences are often silenced—and even attacked—by adoption advocates who insist the process is inherently beneficial for all involved. As Adoptee Mentoring Society Program Director amanda paul put it, “I can’t think of any other groups of trauma survivors who are told to be grateful for that traumatic experience.” Transracial Chinese and South Korean adoptees like paul and Joel Kim Booster are spearheading the push to center adoptees and their unique vulnerabilities in conversations about adoptions, particularly because transracial adoption (which boomed in the latter half of the 20th century) strips adoptees of their nationality and in some cases renders them stateless.

But even for adoptees whose adoptive families share similar backgrounds, the experience of adoption is imbued with harm and alienation. Severing ties between biological parents and children affects adoptees emotionally, mentally, physically, and socially—and often also ethnically, racially, and religiously. (We’ll come back to this last bit in the next section.) In what’s now the United States, that harm and alienation occur in the service of making more Christian Americans—preferably more white Christian Americans, and, failing that, more Christian Americans raised by white parents.

Religion and Adoption in the United States

The largest adoption agencies in the United States are Christian-affiliated, and the relationship between Christianity, whiteness, and American-ness is both well-established and challenging to untangle. Adoption was used as part of genocide and continues to be used in practices of “dekinning” in politicized populations, like migrants. Adoption was used by federal and state governments to destroy “undesirable” families in the name of “saving” the most vulnerable among us. Many Christians pitch adoption as a missionary strategy.

Adoption still is a factor in criminalizing racialized minorities, especially those struggling financially. In 2024, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported that since 2022, children facing poverty and homelessness across Georgia were removed from their families over 1,800 times. We know that people of color are more likely to be policed, more likely to be reported to departments of child welfare as well as more likely to have their children removed, and more likely to be of lesser financial means than white counterparts—which is to say the risk of losing your child, temporarily or forever, are significantly higher for people of color. We also know that white parents are overrepresented in the foster care system and comprise nearly three-quarters of adoptive parents.

There is far more to be said about the entanglements of religion, race, nationalism, and adoption than we can adequately cover here, but just to survey the historical and contemporary landscape:

Orphan Trains

In 1853, minister Charles Loring Brace proposed a solution for the estimated 30,000 “street Arabs” (largely Jewish and Catholic children) who slept outdoors in New York City. Please note that the term “street Arabs” marks the children in question as both not-white and not-Christian, and thus in need of “saving.” Some were orphans; some were solo immigrants; some just found sleeping outside preferable to cramped tenement accommodations. Brace’s answer to this problem? Orphan trains. This man packed a quarter million mostly Catholic and Jewish children onto literal trains and shipped them out west as a source of cheap labor for nice white Christian families. Brace, like many of his time, saw work within the context of a family outside a city as a way to rehabilitate moral failings and their genetic predilections—a way to make religiously and racially inferior children more white, more Christian, and therefore more American.

(Riders of an orphan train. Image source: Kansas State Historical Society/PBS Learning Media)

The Baby Scoop Era

During the Baby Scoop Era (1945-1973)—and yes, that’s really what it’s called—Christian organizations like Catholic charities coerced millions of unmarried pregnant women into surrendering their infants to be placed predominantly with white Christian adoptive parents. (The 1960s alone saw the adoption of two million “scooped” babies.) This period also witnessed an emergence of Jewish adoption agencies precisely because Christian organizations often refused to place children with non-Christian families.

Orphan Theology

Then and now, conservative American evangelical leaders encouraged Christians to embrace what The Child Catchers’ author Kathryn Joyce calls an “orphan theology,” which promotes international adoption as a compassionate response to global poverty, an opportunity to physically and spiritually “save” children supposedly lacking care, and an effective way to go on mission without leaving their own homes. Christian adoption organizations view transracial and international adoptions as a form of missionary work, a way to bring “pagan babies” to Christ.

Adoption and white Christian nationalism

There’s much more to be said about the relationship among religion, adoption, and nationalism than we can cover in this article. With that in mind, we’ll focus on three key elements: how religious freedom, Native sovereignty, and reproductive justice help us better understand the relationship between adoption and religion—and especially between adoption and white Christian nationalism.

Religious Freedom

Most religions have their own approaches to adoption, orphans, and guardianless children—for example, Islam and Judaism favor permanent guardianship, which provides care for children who need it but does not erase ties to their pasts. In this model, the child’s history (their family of origin, ethnicity, name, etc.) are kept intact, even as the adoptive family welcomes the child as their own in every other way. Many adoptees see this as supporting the truth of adoptee existence: we can be like one of your own, but we actually are not. We had a history. Erasing that is violent.

But American adoption systems overwhelmingly focus not on the rights or emotional needs of the adoptee, but of the adoptive parents. Adoptees do not have the right to be raised by adoptive parents who share the religious background of the child. However, adoption agencies (the majority of which are religiously affiliated) and Christian adoptive parents have fought for and increasingly won the right to place and raise children in Christian homes that privilege conservative Christian values—claiming, for instance, that being asked whether they can provide adequate and compassionate care for a queer child violates their religious freedom. And because some states work exclusively with Christian-owned adoption agencies, would-be adoptive parents from non-Christian religious backgrounds can be denied the right to adopt.

Native Sovereignty

Adoption and child theft have also been part of American (and Canadian) strategies of Native genocide and eradicating Native sovereignty—the right of Native people to govern themselves and determine their own futures. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century and continuing until mere decades ago, the residential school system stole Native children from their families, forced them to convert to Christianity, and attempted to “kill the Indian…but save the man” by severing ties between Native children and their families and cultures. Residential schools did not adopt Native children per se but transferred Native children into the dubious care of white Christian educators whose primary goal was to eradicate Native-ness in service of a white Christian nationalist agenda.

But residential schools were merely one strategy to undermine Native sovereignty through the removal of Native children. As we discuss in a recent podcast episode, a 1958 federal initiative created the Indian Adoption Project specifically designed to “stimulate adoption of American Indian children by Caucasian families on a nationwide basis.” (The Indian Adoption Project was just one of numerous federal policies deployed as part of the Termination Era, which attempted to terminate federal responsibilities to Native nations and peoples by essentially eradicating Native-ness altogether.)

White Christian families clamored to adopt Native children, encouraged by ad campaigns in Good Housekeeping and The New York Times. An estimated one-third to two-thirds of Native children were removed from Native peoples and adopted out to white, primarily Christian families during this period. In an attempt to keep Native children within Native communities and preserve a future for Native sovereignty, Dr. Ronald G. Lewis and others drafted the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), which secures the rights of Native nations to determine their children’s futures and preserve their peoples’ cultures—including Native religions.

Native peoples are still fighting to retain custody of their children. As recently as 2022, non-Native white evangelical plaintiffs who wanted to adopt Native children challenged the constitutionality of ICWA. While the Supreme Court upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act, this case highlighted the ongoing challenges Native people, Native sovereignty, and Native religion face in a time of rapidly expanding white Christian nationalism.

Reproductive Justice

Rightwing abortion opponents—again, overwhelmingly white Christians—frequently propose adoption as the moral alternative to abortion. This argument’s logic is flawed: abortion ends a pregnancy; adoption places an alive child in the custody of non-biological parents. But we’re less interested in bad faith arguments about “the rights of the unborn” than in how those arguments get used to constrain pregnable people’s bodily autonomy—and how adoption gets used to bolster laws and judicial rulings that put individual freedoms at the mercy of the state.

While Roe v. Wade (RIP) was the law of the land, the constitution enshrined a person’s right to privacy and thus access to abortion. Movements like the Moral Majority consolidated post-Roe largely around trying to make regressive Christian sexual morality the law of the land; their opposition to abortion manifested as a push to choose adoption instead—addressing a perceived gap in the production of “unwanted” babies available for nice white Christian families to adopt now that abortion was legal. The CDC echoed this anxiety in a 2008 report, which noted that the demand for “domestically supplied infants” was insufficient to meet the demand of American would-be adoptive parents. Justice Alito cited this report—and specifically this turn of phrase—in his opinion for Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022), which voided the federal constitutionality of abortion. That more people want to adopt than there are adoptable “domestically supplied” children is among the reasons Alito argues abortion access should be restricted.

As we know, the majority of would-be American adoptive parents is white and Christian, and the U.S. adoption industry is driven by white Christian organizations. We should and must recognize an imperative for “domestically supplied infants” as part of a larger push to secure white Christian nationalist control of this country for years to come. At first glance adoption might seem like it has nothing to do with religion—but as we’ve shown, this is yet another place where religion is not done with any of us.

Megan Goodwin, Ph.D. is a senior editor for Religion Dispatches, nerd-in-chief at Feral Nerd Consulting, and the media and technology specialist for the Crossroads Project. Her work centers on race, gender/sexuality, politics, and minority religions in what’s now the United States. You can find out more at megan-goodwin.com.

Ilyse Morgenstein Fuerst, Ph.D. is an associate professor of religion and the director of the Humanities Center at the University of Vermont. She writes, teaches, and podcasts about Islam, South Asia, race, religion, and imperialism. You can find all her work at profirmf.com.

***

Interested in more on this topic? Check out episode 55 of the Revealer podcast: “Religion Is Everywhere and Why That Matters.”