AIDS and the Blessings of Staying: The Ministry of Reverend Jim Mitulski

How the minister of a predominantly gay congregation responded to the AIDS epidemic

On August 6, 1995, Reverend Jim Mitulski addressed his congregation, the Metropolitan Community Church of San Francisco, after a month-long absence. He had been in the ICU for three weeks recovering from a blood infection that nearly killed him. As pastor of a mostly gay and lesbian church, he had long been preaching about AIDS. But this was the first time since the congregation and its minister learned that Jim himself was HIV positive.

On August 6, 1995, Reverend Jim Mitulski addressed his congregation, the Metropolitan Community Church of San Francisco, after a month-long absence. He had been in the ICU for three weeks recovering from a blood infection that nearly killed him. As pastor of a mostly gay and lesbian church, he had long been preaching about AIDS. But this was the first time since the congregation and its minister learned that Jim himself was HIV positive.

That day he preached a sermon about the prophet Elijah’s death. The biblical story was one he thought spoke directly to living through the AIDS epidemic in 1980s and 90s San Francisco. But it had taken on new meaning since his diagnosis.

The story recounts Elijah’s travels with his student, Elisha, in the days before his death. At each stop, knowing he will die soon, Elijah tells Elisha he’s free to leave. And each time Elisha responds: “As God lives, and as you yourself live, I shall not leave you.”

When they reach the far side of the Jordan River, they know Elijah’s time is over. Elijah asks Elisha if there’s anything he can do for him before they’re separated. Elisha asks for a double share of the prophet’s spirit. Elijah responds “You have asked a hard thing. Yet if you see me as I am being taken from you, it will be so for you.” Elisha then watches as a chariot of fire takes his friend up to heaven in a whirlwind.

Reverend Mitulski told the church that his stay in the hospital helped him see this story from Elijah’s perspective for the first time. For him, it was a story about the blessings that come when we stay together through times of change, death, and mystery. He recognized that people can’t always stay through such moments, that in a community beset by constant loss it’s sometimes too hard to stay. But if we can, that’s where gifts lie. “That’s it,’ he said. “That’s the theophany. That’s the whirlwind. That’s the still, small voice. When we’re able to stick through with each other in difficult times.”

The act of staying may seem modest compared to a whirlwind, a simple price for something as abundant as double blessings. But AIDS made two things clear. Staying with people whom we love and bearing witness to their suffering, knowing that we will lose them, is terribly hard. And doing it anyway has the potential to be transformative. For Mitulski, it became part of a personal and political theology of AIDS that informed his work as a minister to a community ravaged by the disease, as an HIV-positive gay preacher, and as a progressive coalition-based activist.

Many people turned away from AIDS in the 1980s and 90s. It was new, mysterious, and terrifying. The ways the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) attacked the immune system made people vulnerable to a range of illnesses, known as opportunistic infections, which were rare and fatal. It struck socially marginal people – mostly gay men and IV drug users – and stigmatized anyone with a diagnosis. Fears of contagion made people with AIDS targets of physical and social shunning. Nurses wouldn’t bring food into patients’ rooms. Parents turned away from children. People with AIDS were starved of human touch outside of medical settings. And families were burned out of homes and chased out of towns when neighbors discovered someone with AIDS lived nearby. Staying was neither easy nor assured.

The loudest religious voices of the time, mostly from the ascendant Christian right, encouraged flight. Prominent pastors proclaimed that AIDS was God’s vengeance on sinful people. Allied politicians opposed – and often halted – policies that would have eased the burdens of AIDS. Parishioners and supporters too often assented.

But there were other visions of God at work during those years – a God that stayed with the sick and dying while the world fled, a God that affirmed gay and lesbian love and the families they made, and a God that saw in AIDS the possibility for the liberation of all people. This was the God that Reverend Mitulski and the people of MCC San Francisco reached toward, the God they believed responded with double blessings and more.

***

Jim Mitulski grew up Catholic in Royal Oak, Michigan, a small city on the outskirts of Detroit known as the parish home of radio priest and notorious antisemite Father Charles Coughlin. But for Jim, it was the site of St. Dennis, a newer parish invigorated by Vatican II. Church was a space of safety for him, a refuge from a tumultuous family, and a place of liberal – if not liberation – politics.

His religious life grew through relationships with women. His grandmother, whom he describes as a “total religious fanatic, and eccentric, and kind,” belonged to five different parishes, visiting each weekly. She took Jim with her on these “rounds,” opening his eyes to different Catholic possibilities. As a teenager he became a protégé to Sister Melanie Chateau, a Dominican nun who served alongside two male priests at St. Dennis in an experiment parishioners thought would lead to women’s ordination.

Jim came out in high school in the mid-1970s, although he was never especially closeted. “I never wanted to not be gay,” he said. “I did try to pray for sexual control, but it never occurred to me to try to be straight.” He wrote gay rights editorials in an underground school newspaper and was part of an informal support group for gay teens organized by a lesbian teacher. But coming out escalated tensions in his family.

For guidance, they turned to church. The priests advised Jim’s father to accept his son and supported his mother in doing so. Their counsel gave Jim breathing room in his last years in their home. Smart, literary, and desperate to leave Michigan, he set his sights on Columbia University. He could not imagine a future in ministry as an out gay man, so he dreamed of becoming a poet. He arrived in New York in 1976, an 18-year-old “flaming radical homo feminist.”

***

In New York Jim experimented with bringing his faith, politics, intellect, and sexuality together. He studied religion with progressive pioneers like Carol Christ and Cornel West. He became committed to liberation theology, a Latin American tradition that views scripture from the perspective of the poor and works to free people from oppression. And he got involved in political organizing, holding “Gay is Good” posters at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and gathering signatures for the Equal Rights Amendment. He explored religious life in gay-supportive communities, worshipping with Dignity, a gay Catholic group, and at St. Mary’s Manhatanville, an Episcopal church that sponsored the ordination of Carter Heyward, which paved the way for women to become Episcopal priests. But his own path to ministry remained unclear.

Jim’s activism led him to participate in an annual political ritual of 1970s gay New York. For 15 years, a bill banning discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation went before the City Council. And each year there was a public hearing. At one of those hearings the tension between Jim’s sexuality and his religious life came to a head.

The people he found most morally compelling all supported the bill. But the religious people, with whom he wanted to identify, opposed it with vitriol. “I just fell apart in the hearing chamber,” he remembered. “I started crying and I couldn’t stop. I just thought I can’t be religious anymore.” As he cried, a group formed around him. They were from Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) New York, a church that believed in reconciling homosexuality and Christianity. They recognized his pain and invited him to their church.

The MCC denomination pre-dated Stonewall. It was founded in 1968 by Reverend Troy Perry. A gay, white man from the south, Perry was dismissed from two Pentecostal pulpits because of his sexuality. So he started a church where homosexuality would be seen as a gift from God and compatible with Christian life. MCC preached that gays, lesbians, and other sexual minorities were loved by God just as they were.

The MCC denomination pre-dated Stonewall. It was founded in 1968 by Reverend Troy Perry. A gay, white man from the south, Perry was dismissed from two Pentecostal pulpits because of his sexuality. So he started a church where homosexuality would be seen as a gift from God and compatible with Christian life. MCC preached that gays, lesbians, and other sexual minorities were loved by God just as they were.

MCC also innovated practices that sanctified gay people and gay life. Holy Union, an early form of gay marriage, was a formal rite of the church. MCC congregations also practiced open communion, giving all believers access to the bread and wine shared ritually in remembrance of Jesus’s sacrifice of body and blood. Debate over participation in communion has been vivid throughout Christian history with those deemed sinful, like homosexuals, often excluded. But MCC opened communion to everyone and invited participants to receive it in same-sex pairs and queer kinship groups. This was highly meaningful to gay men and lesbians who had few forums in which their relationships were publicly visible.

MCC New York became the training ground for Jim’s ministry. He became student clergy under Reverend Karen Ziegler, and later an associate minister. Its affirmation of homosexuality put MCC on the fringes of American Christianity, but it was a space where Jim thrived. “The fringe is my home,” he says. “And it’s also where I believe Christianity is. That’s where it finds its meaning.” Working from the margins – rather than from within a larger denomination – allowed MCC to stop fighting over whether it was legitimate to be gay and Christian and build a community that was fully both.

Jim Mitulski in 1978. (Photo: Jim Mitulski’s personal archive)

Jim’s work with AIDS began when it first emerged in the early 1980s. MCC New York was a few blocks from St. Vincent’s, a Catholic hospital that saw many of the earliest cases. Because it was close, and because most of its members were gay, the church was called upon to visit people with AIDS, who were often alone. Jim was one of the team of MCC ministers who responded. In those first years, little was known about the disease and how it was transmitted. He was required to wear a full hazmat suit to enter hospital rooms – “you don’t really want to,” he recalls, “but you don’t know what you’re supposed to do so you put them on.” The disease itself was “painful, messy, ugly, horrible, and fatal.”

Its terror was compounded by the shame of what the disease disclosed about sex and sexuality. In the 1980s many gay men concealed their sexual orientation, including from their doctors. But an AIDS diagnosis laid that bare. Clergy visits to AIDS patients, when made at all, often involved trying to persuade people to repent of homosexuality before death to spare themselves further punishment in the afterlife. Jim and other MCC ministers tried to counter fear of impending damnation by affirming God’s love for gays and lesbians. And they tried to demonstrate it by just being present.

While journalists depicted AIDS as a disease of white gay men, Jim saw many young gay men of color in those rooms. He saw sex workers, people struggling with substance abuse, and people of ambiguous citizenship status. He started bringing a rosary to the hospital with him, visibly wearing it to forge a connection with patients whose languages he did not speak. AIDS showed him firsthand what he had learned from liberation theology – that all forms of oppression worked together and undoing one meant undoing all.

***

In 1986 Jim became pastor of MCC San Francisco. The congregation had been on its own journey to reconcile sexuality and religion since it began in a gay bar in 1970. The congregation purchased a building in the Castro, the city’s gay neighborhood, in 1979. In the year before Jim arrived, a team of laypeople led the congregation and built a religiously engaged community. When he arrived, the week before his 28th birthday, the congregation had about a hundred members and was looking for a leader that could help them navigate AIDS.

San Francisco’s gay community was different than the gay community in New York. So was AIDS. Both cities had large gay populations and neighborhoods where many gay people lived, but the percentage of gay people was higher in San Francisco and they lived in more concentrated neighborhoods. This density facilitated the spread of HIV; case maps consistently showed the Castro as the disease’s epicenter. A vibrant neighborhood in the 1970s, by the mid-1980s it was common to see people with AIDS walking with IV poles. “Now I was living in death village,” Jim says. “But it was not a terrible time.”

Five years into the epidemic, the church had experienced some deaths, but knew a tsunami was coming. The city had developed its eponymous model of AIDS care, relying on volunteer organizations such as the Shanti Project to provide emotional and pragmatic support to people with AIDS. Some of the city’s churches had responded as well – the Episcopal diocese held the first national conference on AIDS sponsored by a Christian denomination. But Shanti, despite roots in the Bay Area’s spiritual counterculture, was reluctant to address religion with its clients. And most church-based responses were tainted by profound ambivalence, at best, toward homosexuality. MCC San Francisco wanted to create a decidedly religious space for people to engage life and death questions of AIDS while countering the notion that people with AIDS were sinners receiving just desserts.

Jim shared that vision. In a city that, even at the time, was almost reflexively “spiritual but not religious,” he was spiritual and religious. As the epidemic unfolded, he saw that religion – gay-affirming, sex-positive religion – had an important part to play in helping the community through it. “Just like the Eucharist and the mass sustained people during the plague, I actually think it did that for us too during AIDS. We were not diseased bodies. We were not infected blood. We took those words [the body and the blood] and claimed them.” For the next fourteen years, Jim and the congregation worked together to respond religiously to AIDS.

***

By 1988 MCC San Francisco understood itself as a church with AIDS. “This doesn’t mean that our church will soon be dead and gone,” wrote Jim and student clergy Kittredge Cherry in an article for Christian Century. “No, in fact it means that we live more deeply.” At that point, two-thirds of the men in the congregation were believed to be HIV positive. And Jim needed to hold the congregation together through seemingly endless waves of grief and loss.

One place those waves hit was at funerals. AIDS complicated the ritual work of remembering the dead and comforting the grieving. Many families of the deceased did not admit publicly that their children were gay or died of AIDS. In traditional funerals, same-sex partners, lovers, and friends who were caregivers often went unacknowledged, their grief unrecognized. Because of its affirmation of homosexuality, MCC San Francisco became a place where people who died of AIDS were remembered more fully and the people who loved them recognized as rightful mourners.

One place those waves hit was at funerals. AIDS complicated the ritual work of remembering the dead and comforting the grieving. Many families of the deceased did not admit publicly that their children were gay or died of AIDS. In traditional funerals, same-sex partners, lovers, and friends who were caregivers often went unacknowledged, their grief unrecognized. Because of its affirmation of homosexuality, MCC San Francisco became a place where people who died of AIDS were remembered more fully and the people who loved them recognized as rightful mourners.

The church did as many as four funerals a week in the 1980s and 90s. Its clergy, headed by Jim, worked to create rituals of memorial that honored people in their complexity. Memorial services became sites of queer ritual innovation that were often heartbreaking and sometimes fabulous. Jim did countless funerals for men he had married only days or weeks before, with their partner’s funeral following soon after. He conducted Richard O’Dell’s funeral where two lovers – one current, one former – were recognized from the pulpit as mourners and given time in the service to remember him. At Scott Galuteria’s funeral the city’s hula troupe danced as his native Hawaiian mother sang the gospel standard “I Come to the Garden Alone.” And Jim still preaches today about Bobby Kennedy’s memorial, where the altar featured the deceased’s prized collection of Fiestaware. Mourners were invited to express their collective anger about AIDS by smashing a dish in his memory.

But the sheer frequency of funerals threatened to drain any given one of its significance. And the compounding of grief could turn sorrow and anger into numbness. “Nothing ever prepared me to do hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of those things.” Jim remembered, “And try to make them not appear like ‘am I doing this again, at two o’clock when I just did one at ten?’”

Grief was only one thing poised to pull the community apart. Fear of illness was another. In a community already stratified by race, class, and age, a new fault line emerged: sero-status – whether a person tested positive or negative for the HIV virus. This biological indicator became a salient social divide in the late 1980s when men tired of condom use sought partners of the same sero-status to minimize the risk of transmission. That divide threatened to become charged with moral significance, separating the perceived bad from the good, the dirty from the clean, and the sinner from the saint.

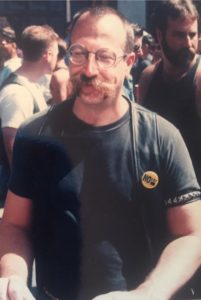

Rev. Jim Mitulski in San Francisco. (Photo: Jim Mitulski’s personal archive)

Jim warned of the dangers of such line-drawing from the pulpit. In 1992 he preached a sermon revealing that while he himself was HIV negative, he was caring for a beloved friend who was HIV positive and was not willing to let difference in sero-status hold them apart. “Positive or negative has a certain medical reality,” he preached. “It does not have to have a spiritual reality in a way that separates us one from the other. It does not have to have a political reality that says there are two kind of people in the world and they can never be together.” He supported separate support groups in the church for HIV-positive and HIV-negative people that addressed each group’s specific issues. But he believed those separate spaces had to encourage coming together and not allow fear, in the guise of righteousness, to pull the community apart.

This became more personal after his own sero-conversion. 1995 was late in the epidemic for San Francisco. People knew about condoms and had been using them for a long time. But grief, frustration, and despair had accumulated past what many could bear, leading to all kinds of risk-taking. “I could write an article just about this, ‘How I Became HIV Positive,’” Jim told me. “And I could write ten different stories and it could all be true.” Once he tested positive, Jim had to face how his diagnosis revealed the risks he had been taking – and to wrestle with internal and external judgment as he asked the congregation to stay with him.

Sero-conversion also galvanized him. It spurred him to write about HIV and call out the moralizing notion that “if you got AIDS early on, it is understandable but if you got it recently, you deserve only to be made an example.” It motivated him to make the connection between AIDS and other forms of marginalization more explicit. And it helped him see that a theology of staying, even through likely loss, offered political blessings as well as personal ones.

***

Jim saw in AIDS the basis for a liberation theology that could spiritually fund political work. AIDS was an opportunity to bring Christian gays and lesbians into broader progressive conversations – and for this largely white, very gay congregation to make common cause with African American churches that were also overwhelmed by the disease.

He preached on race and racism regularly and tried to build relationships with African American congregations affected by AIDS. Some of these early relationships proved too hard to hold. Theological differences on the moral status of homosexuality, the tidal wave of AIDS in the gay community, and other tidal waves, including the crack epidemic flooding Black neighborhoods, dissolved those fragile ties. But when he met Bishop Yvette Flunder, an African American lesbian minister, he recognized the potential for a spiritual friendship with real staying power between themselves, their congregations, and the religious worlds both were trying to change.

When they met, Flunder had just founded Ark of Refuge, one of the first AIDS projects to emerge from the Black church. She was on the ministerial staff of the Love Center, a Black Pentecostal church founded by brothers and music ministry giants Walter and Edwin Hawkins. The congregation drew many same-gender-loving people of color, but being fully out wasn’t an option. Flunder decided to give people that option, founding City of Refuge, which started meeting in the Castro in 1991. The two out pastors built their congregations alongside each other, in ongoing conversation about sexuality, Christianity, AIDS, and race.

When other African American religious leaders became more open in their support of gays and lesbians, Jim provided a pulpit from which they could stand together publicly. Reverend Amos Brown, pastor of one of San Francisco’s oldest African American churches, addressed the MCC congregation in 1996. Brown was a candidate for the city’s Board of Supervisors but faced strong opposition from gay leaders. That changed after Jim had him preach; the sermon was powerful enough to secure Brown the support of the city’s largest gay newspaper. “I wouldn’t have done it,” Jim said, “if I didn’t believe in it. But I felt that the gay community was racist in the same ways that they were accusing the Black community of being homophobic.” He was one of the few gay leaders willing to say it.

Jim’s theology of staying in the face of loss meant staying with communities devastated by AIDS even after effective treatment changed the course of the disease for white gay men in the Castro. The AIDS cocktail, a combination of antiretroviral drugs made broadly available in 1996, was transformative. People at the edge of death returned to life. The hospice around the corner from MCC discharged patients for the first time. There was reason for celebration and a strong pull to move on.

But access to treatment was limited by social inequalities and AIDS persisted as an under-treated, fatal disease in many communities. Jim’s orientation toward coalition work combined with his recent diagnosis made him resist the temptation to step away from AIDS. In a sermon on Gay and Lesbian Freedom Day in 1999, three years after the cocktail, he made his position clear. “We who live in the Castro, who have access to medications may think that AIDS is changing, and it is. But thirty million people in the world do not think AIDS is over. Thirty million people who are lucky to see an aspirin for AIDS treatment do not think AIDS is over. We can’t forget and we must remember.”

***

On Jim’s last Sunday at MCC San Francisco in December of 2000, he preached on Elijah and Elisha again. His years in AIDS ministry had left him exhausted – at 42 he had performed more funerals than most clergy do in a career – and his health needed tending. In the sermon he recalled how people in the community had identified with Elisha in the years before treatment. Throughout the pair’s final journey, observers continually warned Elisha that his friend was dying. This dynamic was familiar to the congregation. Jim reminded them how “medical authorities with their best intentions would tell us in order to break through our denial: you’re going to lose your friend soon. The outlook is bleak. We listened,” he said, “and yet we would also respond as Elisha did to those well-meaning authorities. Shut up! You don’t know the whole story. You don’t know that love is stronger than death. You don’t know that love never ends.”

Then he reminded the congregation who and what to stay with. “We must care about racism and about sexism as much as we care about homophobia,” he said. “Those are our roots. That’s the foundation.” He told them to remember their obligations to other queer groups on the fringe. And he urged fidelity to the preferential option for the poor, an idea from liberation theology that calls for staying – and standing – with society’s most marginal.

“We received a double portion of spirit,” he told them, “because we saw what we were going through. We were attentive. We paid attention. We put our bodies with each other during difficult times of transition and we were blessed beautifully.” By naming the act of staying as the stuff of blessings, Jim recognized the holy sparks in this community’s daily efforts at holding themselves and their loved ones together, however flawed those efforts may have been. In urging them to stay with the people and issues he saw as inseparable from AIDS, he hoped their share of spirit would more than double and that those sparks would grow into flames of justice.

Lynne Gerber is an independent scholar in San Francisco. She is the author of Seeking the Straight and Narrow: Weight Loss and Sexual Re-orientation in Evangelical America from the University of Chicago Press.

***

Interested in more on this topic? Listen to this powerful episode of the Revealer podcast featuring Lynne Gerber: “San Francisco’s ‘AIDS Church’ and the 40th Anniversary of HIV/AIDS.”