Abusing Religion: Polygyny, Mormonisms, and Under the Banner of Heaven

The first installment in a three-part series about stories of abuse in minority religious communities and how they have influenced American culture

About This Series

Americans are having a moment — which I hope will be more than a moment — in which we are taking stories about women’s sexual coercion and abuse more seriously than in generations past. This is an unsettling and important time to be thinking about women’s stories, and the bedrock of any examination, any dismantling of rape culture, must be this: listen to women.[i] Believe women. Their stories matter. We need to hear these stories.

Sharing stories about sexual abuse is not enough, though. These stories are a call to act, to prevent future abuses from happening. But we don’t act on every story of abuse — only certain kinds of stories, about certain kinds of survivors, seem to actually inspire action.

My book, Abusing Religion: Literary Persecution, Sex Scandals, and American Minority Religion (Rutgers University Press, forthcoming), looks at stories about abuse in American minority religious groups. These stories share a common thread: they depict the violation of white American women and children at the hands of religious minorities. And they have inspired massive — indeed, staggeringly disproportionate — responses from the American public through law enforcement, media coverage, targeted legislation, and congressional actions.

Abuse is obscenely common, but few stories of abuse incite raids by armored personnel carriers, news broadcasts that reach millions of viewers, decade-long FBI investigations, or congressional hearings. The stories I write about in Abusing Religion motivated all these responses and more. Americans’ horror and fascination with marginal religions often cause us to correlate religious difference with sexual danger. But we need to take all allegations of abuse seriously, not only the ones that confirm our fears about the inherent danger of sexual and religious difference.

This new series, “Abusing Religion,” will introduce three stories of abuse in minority religious communities, how they caught the public’s attention, and why they are still haunting the American religious imaginary. This first installment traces links between Mormon fundamentalists, Jon Krakauer’s Under the Banner of Heaven, and the American public’s fascination with polygyny.[ii]

SHORT CREEK WELCOME

In 1999, mountaineer and author Jon Krakauer stopped for gas near Colorado City, Arizona — formerly known as Short Creek. Across the highway, he saw a “hazy hodgepodge of half-built houses and trailers…like something out of a Steinbeck novel.” Women working in vegetable gardens wore inexpensive unisex sneakers and “pioneer-style dresses” that reminded him of “Muslim burqas.” When he drove in for a closer look at the settlement, Krakauer received “a Short Creek welcome: … a large 4×4 pickup with darkly tinted windows loomed in his rear-view mirror and began aggressively tailing [him].” Krakauer “couldn’t shake the vigilantes” on his bumper and claimed the encounter “scared the shit out of [him].” Krakauer eventually located a National Park ranger, who allegedly dismissed Krakauer’s concerns. “You were in Short Creek, the largest polygamist community in the country. That’s the way it’s been out there forever.”[iii]

In 1999, mountaineer and author Jon Krakauer stopped for gas near Colorado City, Arizona — formerly known as Short Creek. Across the highway, he saw a “hazy hodgepodge of half-built houses and trailers…like something out of a Steinbeck novel.” Women working in vegetable gardens wore inexpensive unisex sneakers and “pioneer-style dresses” that reminded him of “Muslim burqas.” When he drove in for a closer look at the settlement, Krakauer received “a Short Creek welcome: … a large 4×4 pickup with darkly tinted windows loomed in his rear-view mirror and began aggressively tailing [him].” Krakauer “couldn’t shake the vigilantes” on his bumper and claimed the encounter “scared the shit out of [him].” Krakauer eventually located a National Park ranger, who allegedly dismissed Krakauer’s concerns. “You were in Short Creek, the largest polygamist community in the country. That’s the way it’s been out there forever.”[iii]

Four years later, in 2003, Krakauer published Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith, which parallels the history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with an account of two brutal murders committed by excommunicated Mormon fundamentalist zealots. Banner traces a causal line from religion-writ-large through to the founding and splintering of LDS, to Mormon fundamentalisms (primarily the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints who have historically been based in Short Creek), and ultimately to the murders that anchor the book’s core narrative. If Banner has a moral, it’s that religion is irrational and dangerous. For Krakauer, the evidence of religion’s dangerous irrationality is the Mormon fundamentalist practice of polygyny.

Krakauer’s stated intention in writing Banner was “to grasp the nature of religious belief…to cast some light on…the roots of [religious] brutality [and]…the nature of faith.” But according to Sam Brower, private investigator and author of Prophet’s Pray: My Seven-Year Investigation into Warren Jeffs and the Church of Latter Day Saints, Banner is Krakauer’s attempt to “portray Short Creek as it really was, a place without joy that is run by a Taliban-style theocracy.” Brower claims that Banner “might never have been written if the xenophobic people of Short Creek had not run [Krakauer] out of town.”

Whatever their failings as a community — and the abuse of women and children is always and everywhere a community failing as well as an intimate violence — the Mormon fundamentalists of Short Creek (now Colorado City) have reason to be suspicious of outsiders.

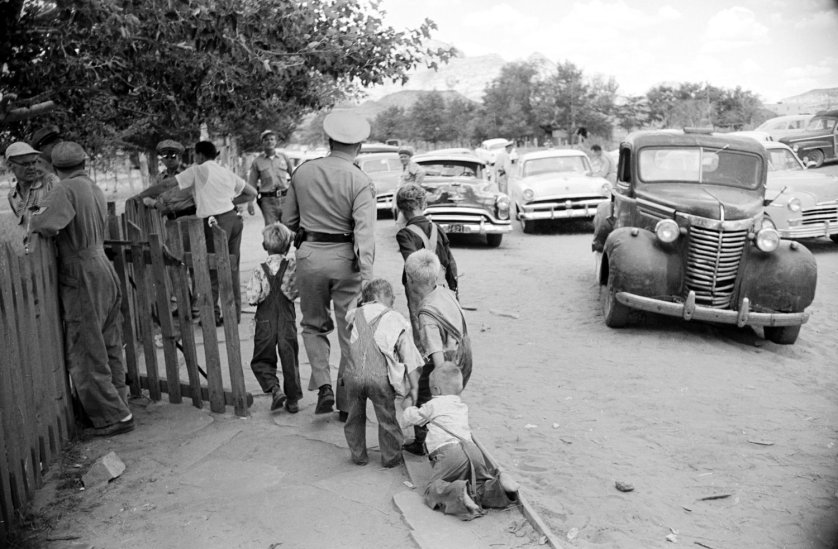

Not published in LIFE. Short Creek raid, Arizona, 1953.

Loomis Dean—Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

In 1953, fifty state troopers and other assorted state officials conducted what Time called “the largest mass arrest of polygamists in American history” at Short Creek. Authorities jailed more than a hundred men, removed most of the women from the town, and placed children with foster families. Some Short Creek children were placed with foster families and never returned home. The people of this small town retreated further into their insular community, increasingly wary of both Gentiles (that is: non-Mormons) and LDS.

Polygamy, Arizona Governor Howard Pyle insisted at the time, was “the foulest of conspiracies,” a “wicked theory” intent on enslaving women. That same year, Deseret News applauded the governor’s attempt to eradicate the practice before it became “a cancer of a sort that is beyond hope of human repair.”‘[iv]

WHO ARE MORMON FUNDAMENTALISTS?

Mormon fundamentalists trace their spiritual lineage back to Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, just like members of the more mainstream Latter-day Saints (LDS) Church.[v] In 1852, President[vi] Young revealed Doctrine and Covenants 132, which included “The Principle” celebrating the salvific potential of polygynous, or plural, marriage.

But in the late nineteenth century, a post-Civil War federal government insisted that Mormons abandon the practice of polygyny to reclaim Church property and gain statehood for the Utah Territory. President Woodruff revealed that the Church would no longer consecrate plural marriages.[vii] The Woodruff Manifesto caused a series of schisms and led to the formation of numerous Mormon fundamentalist sects. The largest of these sects is the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS), led by Warren Steed Jeffs. There are a number of practices that set Mormon fundamentalists apart from LDS, but the American public has been most consistently concerned with the practice of polygyny.

After the 1953 raid, public opinion largely sided with the residents of Short Creek. Plural marriage remained illegal but mostly avoided both legal prosecution and national attention for decades. A few high-profile outlets covered Mormon fundamentalist communities: the New York Times reflected on the “Persistence of Polygamy” in 1999; in 2000 and 2001, several news outlets reported that Jeffs had required FLDS parents to remove their children from public schools. The 2002 kidnapping of Elizabeth Smart drew national attention again, but her fundamentalist abductor’s religious identity remained a confusing detail in most news coverage. Americans — those living outside Colorado, Utah, and Arizona, in any case — remained largely ignorant of Mormon fundamentalists’ practices or existence until Jon Krakauer’s 2003 blockbuster turned the spotlight on FLDS.

BEYOND BANNER

Under the Banner of Heaven is a deeply flawed but indisputably influential work of pulp nonfiction. Doubleday issued a massive first printing of 350,000 copies, and the book garnered rave reviews from major news outlets, including the New York Times and Newsweek. Krakauer’s blockbuster titillated millions of readers with lurid details of exploited girls and young women within the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Throughout Banner, Krakauer locates the root of this violence against women in religion, frustrating scholars and believers alike.

For Krakauer, religion is abuse. And in the case of FLDS, that abuse takes the form of polygyny. In Banner and throughout his subsequent anti-polygamy activism following its publication, Krakauer draws no distinctions between plural marriage among consenting adults and the sexual abuse and coercion of women and children. (Indeed, the voices of consenting adult women in plural marriages are completely absent from the book.)

Krakauer’s post-Banner activism largely focused on finding and apprehending Warren Steed Jeffs, who seems to embody polygamy-as-abuse for the author. Warren Jeffs faced federal charges within a year of Banner’s 2003 publication, made the FBI’s “Most Wanted” list in 2006, and was arrested three months later on charges related to the sexual exploitation of FLDS girls and young women.[viii]

By his own admission and according to Brower’s account in Prophet’s Prey, Krakauer “obsessively” involved himself in the hunt for Warren Jeffs, contributing thousands of dollars of his personal wealth to the cause. Krakauer and Brower worked together to “alert” Texas law enforcement that an FLDS community led by Jeffs had moved into Eldorado.

By his own admission and according to Brower’s account in Prophet’s Prey, Krakauer “obsessively” involved himself in the hunt for Warren Jeffs, contributing thousands of dollars of his personal wealth to the cause. Krakauer and Brower worked together to “alert” Texas law enforcement that an FLDS community led by Jeffs had moved into Eldorado.

During the fall of 2004, Krakauer and Brower personally “scouted” the FLDS property, attempting to “serve papers” to Jeffs. They conducted “daytime surveillance” by hiking through deep woods to the north of the commune, and returned after dark with night vision goggles to try to gather the license plate numbers of Jeffs’ support staff. In January 2005, Krakauer accompanied Brower on a small private flight over the FLDS-owned Yearning for Zion Ranch, successfully photographing Jeffs standing in the middle of a prayer circle.

Jeffs is currently serving a life sentence plus twenty years for two felony counts of child sexual assault and remains President of the FLDS. But Krakauer’s crusade to bring Jeffs to justice had effects far beyond one man’s incarceration.

In April 2005, as part of an emotional appeal to pass legislation directly targeting FLDS as a dangerous sect, Krakauer told the Texas House of Representatives’ Committee on Juvenile Justice and Family Issues that FLDS is dangerous, specifically because they practice plural marriage. Krakauer called polygamy “the bedrock of [FLDS] culture,” and warned that “these abuses [that is, of women and children] seem to be part and parcel of every polygamous culture.” (There were no FLDS women or children present at this hearing, and a member of the committee commented that even if FLDS members had been present, the committee would not have recognized them.)

Krakauer’s testimony before the Texas House of Representatives also helped convince state officials that the entire FLDS community in Eldorado was sexually suspect. Despite having received no complaints of abuse, the Committee for Juvenile Justice and Family Issues swore that they would “go after” this marginal religious community, insisting that they would “be a little more creative in how we get the report” of sexual abuse from “inside” the FLDS Yearning for Zion ranch.

In April 2008, a series of phone calls from a woman calling herself Sarah Jessop gave the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services probable cause to investigate the community at Yearning for Zion.[ix] In an unprecedented move (later criticized by the state’s supreme court), law enforcement and child protective services raided the Yearning for Zion ranch soon after. This “military-style raid” — 55 years after the raid in Short Creek — deployed heavily armed officers and armored personnel carriers against US citizens, produced very little evidence of abuse, and separated nearly 500 children from their families — the single largest custodial seizure of children in American history.[x]

Faced with the seemingly-permanent loss of their children, the women of FLDS appealed directly to the public. Marie, separated from her three sons after the raid, explained that “they think we are brainwashed, or whatever,” she sobbingly told reporters. “Who can you tell? Who will believe that they’re really happy? The children are so happy… They are being abused from this experience [of being forcibly separated from their families]. They haven’t known abuse until this experience.”

EXPECTING ATROCITY

The assumption that polygyny constitutes abuse motivated the raid on Yearning for Zion, a Mormon fundamentalist community in Eldorado. The raid garnered massive news coverage, including over thirty stories in the New York Times alone, a special episode of Oprah in 2009, and a series on Anderson Cooper 360. American media outlets remain interested Mormon fundamentalists: Anderson Cooper 360 reported on a family’s “escape from the FLDS church” again in 2013; the Oprah Winfrey Network did a “Where Are They Now?” retrospective in 2015; and dozens of feature-length stories on Mormon fundamentalists have appeared in Rolling Stone, Cosmopolitan, Teen Vogue, the BBC, Al Jazeera America (RIP), and most recently, Buzzfeed (RIP?).

Krakauer might have whetted Americans’ appetite for lurid tales of polygynous depravity, but he certainly did not exhaust it. His narrative, and those he facilitated (however indirectly), remain a constant source of fascination for American audiences. His interventions contributed to the capture and imprisonment of Warren Jeffs, a man who damaged and abused the community who trusted him to lead them. Banner also made space for more (and more nuanced) depictions of Mormon fundamentalism in the public sphere. At the same time, Americans’ fascination with polygyny has produced more — and more nuanced — depictions of plural marriage and Mormon fundamentalism.

In 2004, shortly after the publication (and popularity) of Under the Banner of Heaven, HBO greenlit “Big Love,” an Emmy-nominated and Golden Globe-winning fictional — but surprisingly sympathetic — look at contemporary Mormon fundamentalist polygyny. “Big Love” ran for five seasons. In 2010, TLC began airing “Sister Wives,” a reality show featuring a Mormon fundamentalist family. “Sister Wives” averaged millions of viewers in its first season and is still on the air. Other reality show treatments of Mormon polygyny include “Polygamy, USA” (National Geographic, 2013), “My Five Wives” (TLC, 2013-2014), “Escaping Polygamy” (A&E, 2014 – present), and most recently the Channel 4 docuseries “Three Wives, One Husband,” which Netflix added in late 2018. At least twenty-three memoirs about Mormon polygyny were published between 2004 and 2017. Documentary filmmakers have produced at least seven films produced on plural marriage and Mormon fundamentalism since 2005, including Sons of Perdition (2010) and Prophet’s Prey (2015, based on Brower’s book of same name).

HBO’s “Big Love” promotional photo

Many of these programs still exoticize polygyny: “escape” and “abuse” and “survival” are consistent themes in many of these shows, books, and films. But shows like “Big Love,” “Sister Wives,” and “Three Wives, One Husband” all provide Mormon fundamentalist women in plural marriages a platform to advocate for themselves and resist depictions of polygynous women as brainwashed, coerced, stupid, or weak-willed. This is a core theme in the opening credits of “Sister Wives”: Meri Brown says that she “believes in living this lifestyle” because “it just makes each of us better,” while Christine Brown clarifies she “like[s] sister wives” and “wanted the family, I didn’t just want the man.” The voices of consenting Mormon fundamentalist women, so lacking in Under the Banner of Heaven, are nevertheless present in the media Banner helped popularize.

Polgyny is unusual, but that does not necessarily make it abusive. The conditions that facilitate abuse — poverty, isolation, patriarchal family structures — are not unique to Mormon fundamentalist communities. Neither sexual nor religious difference make abuse any more or less unlikely to occur. Under the Banner of Heaven and its pulp nonfiction ilk attempt to bring stories of abuse to light, presumably to stop ongoing abuses and prevent future ones. And the voices of abuse survivors absolutely deserve to be heard.

So too, though, do the voices of women who willingly enter into the covenant of plural marriage. Krakauer’s work is laudable for its attempts to make women’s suffering visible, but the silence of Mormon fundamentalist women throughout his work is deafening. Listening to women requires hearing voices that disrupt as well as confirm our suspicions.

***

[i] And other survivors of violence, coercion, and assault, of course. I focus on women’s stories not because they are more important than those of other survivors, but because stories about white women and children being abused are most effective at inciting public response.

[ii] Polygamy refers to any marriage of multiple partners and is the most common term used by outsiders to describe Mormon fundamentalist plural marriage. But Mormon fundamentalist plural marriages are exclusively polygynist, marriages of one man to multiple women. Mormon fundamentalist doctrine permits — and in some cases encourages — this form of “plural marriage” while proscribing polyandry, the marriage of one woman to multiple men. See Doctrine and Covenants 132: 54-55.

[iii] All quotes from Brower, Prophet’s Prey (2011).

[iv] Deseret News is a Utah paper funded by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS).

[v] LDS officials would contest this definition.

[vi] The head of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is known as the President of the Church; he also serves as prophet, seer, and revelator.

[vii] For more on this, see Sarah Barringer Gordon’s excellent The Mormon Question. Additionally, while the 1887 Edmunds Tucker Act revoked women’s suffrage in an attempt to discourage polygamy, the state’s 1895 constitution reinstated the right to vote for all white Utahans. State and federal governments have been deeply invested in regulating women for quite some time.

[viii] Jeffs’ conviction was overturned in 2010, after which he was extradited to Texas and convicted of sexual assault and aggravated sexual assault of children in 2011. He continues to serve as President and Prophet to FLDS from the jail cell he will occupy for the rest of his life.

[ix] “Jessop” was in fact Rozita Swinton, a woman who never lived at Yearning for Zion and has a history of false reports of abuse.

[x] Little evidence, however, is not an absence of evidence. Twelve FLDS men, residents of Yearning for Zion, were indicted on charges related to underage marriages. Warren Steed Jeffs is currently serving a prison term of life plus twenty years for the sexual assault of a twelve- and fifteen-year old girls, whom Jeffs had taken as wives. Nine other FLDS men were convicted of abusing or facilitating the abuse of twelve children at Yearning for Zion.

***

Megan Goodwin (PhD UNC 2014) is a scholar of gender, sexuality, race, and contemporary American minority religions. and the Director of Sacred Writes at Northeastern University, a project committed to amplifying the voices of experts who often go unheard in public discourse. Her current book project, Abusing Religion: Literary Persecution, Sex Scandals, and American Minority Religion (Rutgers University Press, forthcoming), explores the coding of religious difference as sexual danger. Her next project considers the ways contemporary American whiteness is (or feels) threatened by Muslims and Islam. Goodwin is the co-chair of the American Academy of Religion’s New Religious Movements Program Unit and a former co-editor of Religion Compass’s Religions in the Americas section.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs