A Sanctuary for Abortion: How Sanctuary Reveals the Fears of Our Time

California’s plan to make the state a refuge for abortion access builds on a long history of sanctuary movements in the U.S.

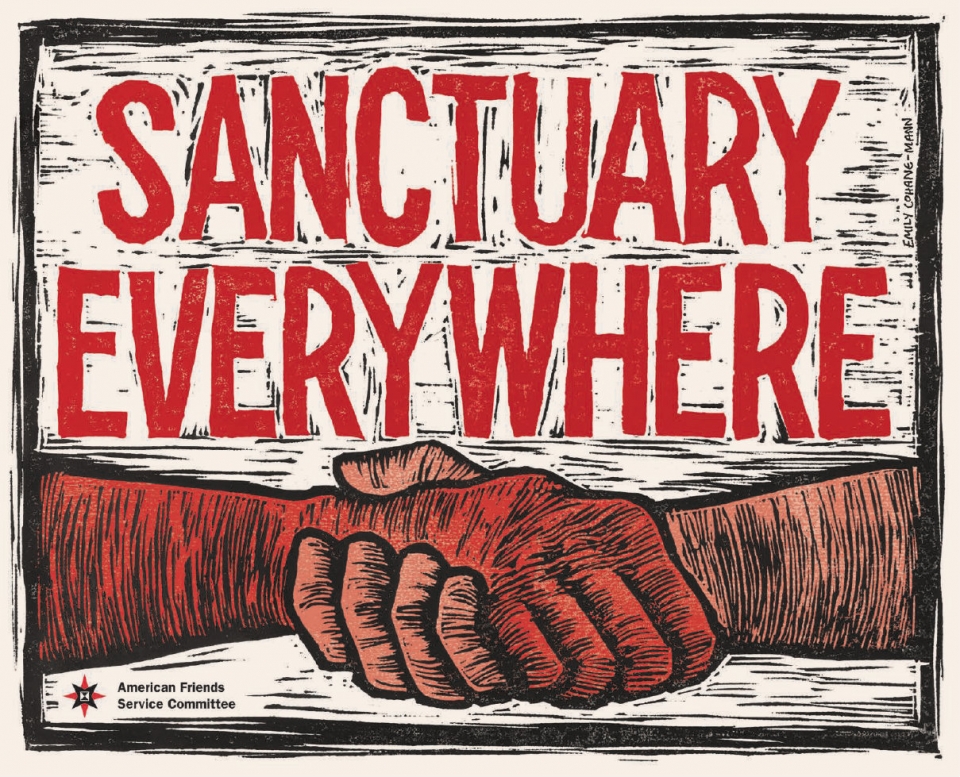

(Image source: American Friends Service Committee)

One sign of our increasingly divided country is the reemergence of “sanctuary” as a political strategy. In response to concerns that Roe v. Wade might be overturned, California has launched a push to become an abortion sanctuary, ensuring that citizens of other states and its own have access to safe abortions. When asked to summarize the proposal, Governor Gavin Newsom quipped, “we’ll be a sanctuary.”

As a scholar of sanctuary movements and as an ordained minister serving a church in the New Sanctuary Movement, I have been tracing sanctuary’s increasing relevance with a mix of hope and caution. Addressing citizens’ fears that abortion could soon be illegal is an important component of California’s proposal. That makes sense, as calls for sanctuary are typically a response to a catastrophe that offers a space where laws might not apply. California’s proposal is no different, as it imagines a future in which abortion is no longer constitutionally protected.

***

Sanctuary gets its start in the biblical tradition with the creation of altar sanctuaries, whereby a monarch might offer clemency to people in fear for their lives. In both cases where this takes place in the Bible (1 Kings 1:50; 1 Kings 2:28), the altar serves as a place where the normal laws do not apply and the monarch’s mercy can intercede (or not). By the 9th century B.C.E. the aberrational space of altar sanctuary eventually developed into a system of cities of refuge, where those accused of accidental homicide could flee in order to escape vengeance.

In the Middle Ages, sanctuary enjoyed a resurgence as individual churches served as places to which accused criminals could flee for a period of time before submitting to authorities, joining a religious community as lay brothers, or entering a voluntary exile. This form of sanctuary remained in use until the 16th century, when governments began to strive for more orderly and uniform law and sovereignty. Still, the tradition safeguarded asylees, giving them valuable time and space to discern their next course of action and even to save their lives through abjuration.

Modern sanctuary movements have marshaled the idea of houses of worship as safe places, where laws are symbolically, if not legally, annulled. During the Vietnam War a thriving sanctuary movement took root in the Bay Area as places of worship housed those who refused military service. Centered mainly on naval vessels in the Bay Area, churches came together to offer sanctuary in response to service members’ fears that they would be imprisoned or shunned. Houses of worship, demonstrators, and petition signers showed that the public cared about draft resisters and service members who refused to join the war, even enough to withstand threats of prosecution from the U.S. Attorney in San Francisco. Their fear transformed into solidarity. Acting as part of broader networks, such as the Stop Our Ship campaign and general resistance to the Vietnam War draft, religious leaders leveraged their privileged status to grant temporary safety for those resisting deployment.

Other moments of sanctuary during the Vietnam War assisted protestors and political radicals as opposed to service members. In 1969 in Cambridge, MA, a church housed Eric Mann, the leader of a radical anti-war organization, allowing him to give a speech condemning the Vietnam War before he gave himself up to authorities. The church also served as a sanctuary for those fleeing police during a Vietnam War protest in 1969 that dominated student life at Harvard University. Fear was a fundamental part of the Vietnam War sanctuary, as soldiers feared being forgotten, radicals feared prosecution and imprisonment, and protestors feared police beatings. The number of sanctuaries in the Vietnam War has not been counted, but houses of worship, cities, and campuses comprised the network. That network had an outsized importance in the sanctuary movement that would follow, as clergy took lessons from the 1960s and 70s and applied them to new contexts.

The Sanctuary Movement of the 1980s began with compassion alongside fear. In 1980, Quaker Jim Corbett and Presbyterian minister John Fife encountered great suffering and death among Central Americans – largely Guatemalans and Salvadorans – who were attempting to cross the border into the United States. Corbett and Fife also found that asylum cases for Guatemalans and Salvadorans were denied at an astonishing rate, with judges unwilling to hear accounts of torture as part of the asylum process. What started with compassion evolved into a complex set of anti-interventionist aims, with about 500 houses of worship joining the movement.

(Image source: David Zalubowski for Associated Press)

Leaders of the 1980s Sanctuary Movement used the media to amplify their message, which started when Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson and five other congregations simultaneously declared their houses of worship as sanctuaries for Central Americans. Their media message was simple: places of worship would house “refugees,” the preferred term of activists, and give them a platform to share their stories in a publicized testimonio, often in local media. These narratives countered the Reagan administration’s propaganda about Guatemala and El Salvador and led to a groundswell of support. When appearing before the public, sanctuary recipients often wore a bandana to protect their identity, and were pictured front and center in many news articles of the time. In the Bay Area, those who took part in the sanctuary movement for service members in the Vietnam War took those lessons and applied them to this new crisis, citing their previous sanctuary experience as important preparation. Eventually, a change in administration and a key court victory guaranteeing a fairer asylum process – ABC v. Thornburgh in 1991 – meant the gradual winddown of the this iteration of sanctuary, but those same activists would later influence a new movement for undocumented immigrants.

***

The New Sanctuary Movement claims many dates for its beginning, but 2006 saw the revival of the strategy. In August of that year, Elvira Arellano entered sanctuary in the Adalberto United Methodist Church in Chicago. She did so to avoid deportation and separation from her children. From there, the movement spread to more cities, each mobilizing the tactics of the 1980s to fight against the United States’ immigration policy. Highlighting the cruelty of deportation, undocumented migrants took a lead by telling their stories and often using their real names. Churches provided them housing and relied on Immigrations and Customs Enforcement’s rules against entering a church building to safeguard the undocumented. The New Sanctuary Movement’s strategy hinged on humanizing the immigration issue, a point Arellano highlights when she says, “We are tired of hearing so many lies about us. Our lives shouldn’t be talked about like game matches. This is a humanistic issue.” The New Sanctuary Movement continues in the present day and claims some 1,100 faith communities, including the one I serve as pastor.

What many miss about these movements is how central fear and catastrophe were to their genesis. For those about to be deployed to Vietnam, fear was understandable, but clergy and laypeople were concerned about a moral calamity befalling the nation. This sense of moral failing can be grasped from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Beyond Vietnam” sermon, which he delivered to over 3,000 people at New York’s Riverside Church in 1965. In it, he says, “If America’s soul becomes totally poisoned, part of the autopsy must read: Vietnam.” In the face of a moral calamity, clergy who opened their doors chose action through sanctuary, forming a node in the religious anti-war nexus that included the Berrigan Brothers and Clergy and Laity Concerned About Vietnam.

The Sanctuary Movement of the 1980s was also fundamentally grounded in fear, since fear was the central qualifier for refugee status under the Refugee Act of 1980. Recipients of sanctuary gave testimonials in which they cited their own fear and indicted the United States’ complicity in supporting the regimes that caused them to flee their home country. These reports helped to mobilize religious liberals in opposition to Reagan’s policies, which they saw as a moral duty. Those religious liberals were often underestimated, as an FBI report of their activity reads: “Aside from the old people, most of them looked like the anti-Vietnam war protestors of the early 70s. In other words, political misfits.” Those “misfits” would go on to form a valuable volunteer corps of politically engaged activists.

***

Sanctuary is intended to convert fear into action, which is certainly the case in California’s abortion sanctuary proposal. Abortion access is tightening across the United States. Fearing a change in federal policy, Governor Newsom convened The California Future of Abortion Council, which released some 45 recommendations in its December report. Like other sanctuary movements, it centers personal testimony about the coming catastrophe that abortion advocates worry will take place if the Supreme Court repeals Roe v. Wade.

One portion of the report, which quotes Senator Toni G. Atkins, Senate President pro Tempore of the California Senate, reads: “I talked directly with women who had found their way to our clinic for assistance because they lived in states with restricted access. I met a mother who lost her daughter due to an illegal abortion. We can’t afford to let extremists turn back the clock on our rights.” Much like the testimonio of the Sanctuary Movement of the 1980s, the fear that sanctuary movements cite as their raison d’etre is both personalized and systemic. For California’s abortion sanctuary advocates, the erosion of the “constitutional right to abortion” will have catastrophic consequences “as other states adopt extreme bans on an essential health service.”

(Image source: Los Angeles Times)

California’s abortion sanctuary proposal presents many considerations. Perhaps the most important is the realization that the states surrounding California have either unclear or oppositional stances toward reproductive rights and some 1.4 million people will have California as their closest access point for abortion, a nearly 3,000% increase from the current situation. The proposal advocates for increased infrastructure, access, and equity within California’s system, as well as a removal of barriers for accessing reproductive care for those traveling from out of state. A recent proposal also calls for student loan forgiveness and help for healthcare providers that commit to performing abortions. Overall, advocates want California to be a place where getting an abortion is easier for residents and a place of refuge for those in other states where the right to abortion has been abrogated.

Clergy are not the current leaders of California’s abortion sanctuary movement, but the movement deploys similar strategies and utilizes the language of previous sanctuary movements. Far from a mere linguistic dependence, California’s proposal stands in a long line of activists who want to resist federal policy, even if that change in federal policy is only imagined at this point. As Roe v. Wade is still in effect, California’s abortion sanctuary proposal gives a glimpse into the fear that drives the creation of sanctuary activism.

Notably, faith leaders across the United States are mobilizing to protect access to abortion. At a recent national conference organized by Spiritual Alliance of Communities for Reproductive Dignity (SACRED), religious leaders described the need for a faith-based movement to protect the right to abortion. While sanctuary was not the term of choice for these activists, SACRED helps religious communities “make the sacred space safe” for those seeking reproductive care.

***

Whether the activists are religious or not, sanctuary seeks to create spaces that symbolically annul federal policy. The Sanctuary Movement of the 1980s did not enjoy legal protection from federal enforcement. Their protections instead relied on internal policy that agents exercise discretion when dealing with houses of worship. Such discretion did not, for instance, protect the Sanctuary Movement of the 1980s from surveillance in churches or infiltration of the movement through undercover operatives under the code-name “Operation Sojourner.” In the same way, California’s proposals will not restore abortion access in other states, but it will offer tangible and symbolic resistance to the erosion of abortion access.

Sanctuary movements are built in the middle of crisis, and that crisis is not unique to progressive sensibilities – conservatives also utilize sanctuary as a strategy. Take, for instance, the Sanctuary Cities for the Unborn Movement, which seeks to use municipalities to annul state and federal protections for reproductive rights. Its legal innovations gave rise to Texas’ recent law that imposes civil penalties on those who facilitate abortions for pregnant people after 6 weeks – a time frame before many people know they are pregnant. Second Amendment advocates are also pioneering sanctuary strategies to fight back against state laws that restrict gun ownership. In both cases, the movements are grounded in fear of a coming catastrophe – one that would enable more access to abortion or less access to firearms.

The success of sanctuary movements is debatable and depends largely on how one judges sanctuary’s goals. For instance, the Sanctuary Movement of the 1980s did generate media interest in Central America and produced measurable changes in the United States’ asylum policy. Its legacy lives on through sanctuary cities and sanctuary campuses that dot the American landscape. The New Sanctuary Movement similarly produced much media interest, but there have been no major changes in immigration law. What seems clear is that sanctuary is a strategy whereby activists create symbolic solidarity; those symbols have real power, but there are also limits to their effectiveness.

The effectiveness of sanctuary as a symbol lies in its ability to articulate the fears of any given moment and link inaction with complicity. Each movement is clear about the approaching catastrophe that a shift or entrenchment of laws might produce – a world that is less just, crueler, or more restrictive are common manifestations of this fear. But those apocalyptic visions often contradict one another, making sanctuaries sites of contest and struggle over what vision of America ought to be pursued. What seems clear to me as someone who has studied sanctuary movements for several years is that if one wants to trace the contours of fear at the heart of our polity, sanctuary is a good place to look. A common refrain among sanctuary activists is “sanctuary everywhere!” From the looks of it, that may be exactly what we will be experiencing. However, what that portends for our nation is an open question.

Michael Woolf is a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard Divinity School and the senior minister of Lake Street Church of Evanston, IL. He is an ordained American Baptist minister and holds a Doctor of Theology degree from Harvard Divinity School. He writes about sanctuary, theology, and reparations. Follow him on Twitter @RevMichaelWoolf.