The Patient Body

A Normal Woman

“The Patient Body” is a monthly column by Ann Neumann about issues at the intersection of religion and medicine. This month: When are women's bodies considered normal?

Now Abraham and Sarah were old and well stricken in age; and it ceased to be with Sarah after the manner of women. Therefore Sarah laughed within herself, saying, After I am waxed old shall I have pleasure, my lord being old also? Genesis 18: 11-12

When the King James Bible was first published in the early 1600s, a small fraction of women lived long enough to reach menopause, their lives ended by age 35 or 40 by famine, disease, war, poor nutrition, untreatable illnesses, contaminated water and food, and, of course, childbirth. If female pleasure was considered at all in the Bible, it was the pleasure of fertility. Or sin. Today, women have a life expectancy that is nearly double what it was 500 years ago. The ensuing centuries have added another 40 years to the female lifespan. Many of those additional years are spent in peri-menopause, the period of time when fertility fades, or menopause, defined as when a woman has ceased to menstruate for a period of 12 months. Barrenness, whether by choice, reproductive incapacity, or age—at least in so-called “developed” countries—is for an increasing number of women, the new normal.

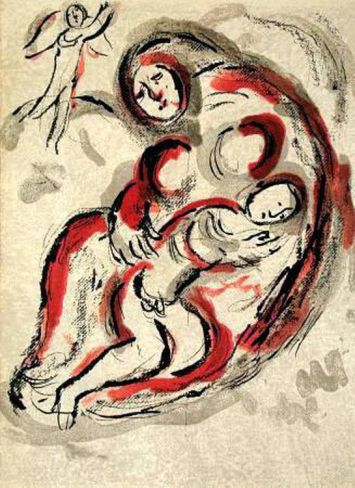

Ève maudite par Dieu (Eve Incurs God’s Displeasure) by Marc Chagall

Not that many faith traditions, medicine, or even our culture have caught up to this new female normal. Fertility, then and now, is often the defining characteristic of womanhood. (In a recent review of the current revival of Edward Albees “Three Tall Women,” Hilton Als writes that mother is “the greatest roll onstage and off.”) A woman’s purpose is so universally reduced to reproduction—through pregnancy, motherhood, and their accompanying traits: nurturing of others, caregiving, patience, self-sacrifice (of time, self-care, and even life), tending to a home, and the fostering of community—that we’ve struggled for centuries to acknowledge that beyond the baby, she also has value to society. Women are the village that childrearing requires. Every other ambition she may have is superfluous.

My own return to normal began with hot flashes last year, a few weeks after having my ovaries laparoscopically removed. The estrogen they were producing caused palpable endometrial masses to form in my abdomen. For the course of my adult life, it was my unwavering choice to not have children and remaining childless was a luxury that cost me great effort and expense—a luxury, I acknowledge, few women can afford. The irony of my over-active ovaries was not lost on me. They were now finding alternative purposes. At long last, surgery, and of course age, had taken choice out of it. The plumbing was no longer intact.

I don’t miss my ovaries, of course. Most of the romance of motherhood was long ago lost on me. But surgery gave me a new understanding of what it means to be a post-reproductive woman in American society—or as an older friend says, I began having “crone insights.” Almost overnight, the incredible skill, shame, coercion and resources that society employs to perpetuate the human reproductive project was laid bare to me—and eventually became the best solace a menopausal woman could ever have: the embodiment of the knowledge that my value as a human being could be deemed by something other than my physical desirability. I could just be a human. And that could be enough.

Agar dans le Désert (Hagar in the Desert) by Marc Chagall

While little about my appearance changed in the immediate period after surgery, at least to an outsider, I was a new being, released from the responsibility of catering first to men’s attention and then to family’s. Survival of the human species was no longer on my shoulders. In its absence was the liberation to please not others but myself. I could dress for myself, spend my time on my own work, keep house (or not) as I chose. To be clear, I’ve been single for a decade so my domestic obligations haven’t changed. But what has changed is the pressure to have a certain kind of more—a man and children. I was also relieved of the imposed apology (as in the cocktail qualification: “no, I’m single, no, I have no children.”) I was no longer defined by the absence of something. I could just be myself. All the pressure to be something in addition to an independent person became, at last, unimportant to me.

The cultural cache afforded to mothering—rather than being a woman—is explicit in our language. Female writers birth books, ones that we are often paid less for than men because, of course, our real labors reside elsewhere. Our bodies have never been our own; they belong to the state (which tells us what to do with them), to our husbands (who are free to do with them what they wish), to our children (who need every form of our attention for survival), and to our bosses (who have long put a price on us according to our appearance—think: rampant sexual assault—or our supposed outside obligations to family).

Until barrenness was physiological, I was still tethered to the pervasive and persistent construction of what a good woman must be, if not for myself, for the comfort of others. The conflicting attributes are recognizable to us all: sexy, but not too sexy; young; passive, or if a tiger, a tiger mom; if deviant, in the service of sexy; emotionally accessible, but not too emotional; independent, but not outspoken; ambitious, but not too ambitious. Snip-snip and suddenly I was not beholden to anyone.

Women, I understood at my surgically altered core, spend their early decades focused on how and when and if to have babies; once menopause arrives to undermine all our prized ideas of youth and beauty, compatibility and deference, we acknowledge why such attributes are prized in the first place. Quite often the answer is: for our own subjugation.

For decades, studies have shown that women live longer, earn more, and obtain higher levels of education if they control their fertility or remain childless. Still, most studies (including those linked above) approach the question of women’s improved circumstances from the other way around. For instance, does enrollment in graduate school decrease childbearing? The assumption is that childbearing and rearing are an unquestionable good prevented (hindered, thwarted) by other types of “achievement.”

The message of this frame has been loud and clear since the early days of modern medicine, when Margaret Sanger struck fear in the heart of our Godly nation by founding the American Birth Control League: women without children are a problem to be solved, regulated, controlled, and cured. Which explains why childlessness is either something that must be medically fixed (if you have the money) or the secret shame, the thing that must not be discussed.

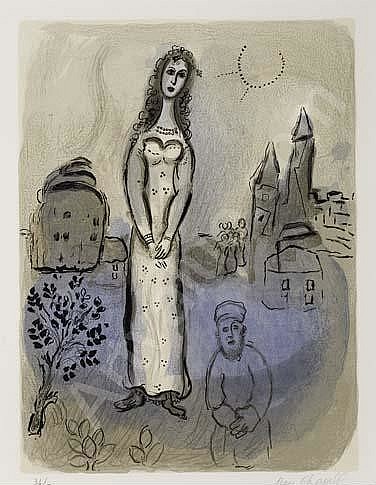

Esther (Esther) by Marc Chagall

Dominant faith groups in the US have been the gatekeepers of this limited idea of woman. By systematically keeping women from leadership roles, by preaching female submission from the pulpit, by failing to acknowledge the trials of women’s domestic lives and child birthing, the loudest denominations and leaders, with both feet in the culture wars, have worked to prevent any kind of male-female equality (beyond the false “separate but equal”). Purity culture, male headship, and rules for Godly women (and the men looking for them) have all entrenched female inequality.

Our faith traditions have emboldened legislators who continue to ignore the inequality of women’s lives. The rub here of course is that even when we fulfill our wifely and motherly duties, we’re still second class citizens. Consider the epidemic of neglect of women’s medical needs, including the inadequate treatment or mistreatment of female pain, the failure to test new drugs on women, particularly pregnant women, anemic research about ailments that predominantly afflict women, and, of course, the paucity of attention to menopause.

“Despite the fact that for millions of women their menopausal symptoms are intolerable so many are suffering in silence because it is a taboo subject and treatment options are limited,” Dr. Julia Prague told Science Daily last year about her study on a new drug treatment for hot flashes, one of the many physical challenges menopausal women face. Attention deficit and lack of concentration, vaginal dryness, hair loss, drying and thinning skin, fatigue, muscle soreness, mood swings, weight gain: these are only a few of the 34 symptoms of menopause. (Many suffering women, I think, would conclude that this list is abbreviated.) Each symptom is like a strategic attack on what our society has deemed the most becoming characteristics of femininity. Still, for instance, medicine has not isolated the cause of hot flashes, the ostensible first step in alleviating hot flashes.

In a 2011 article for The Atlantic, Sandra Tsing Loh wrote about embracing her menopause—the anger, frustration, mood swings, crying, and the throwing off of the caretaking mantle women are forced to wear. The piece is titled, “The Bitch is Back,” and challenges women to see their menopausal years as the normal years, consistent with our pre-menstrual lives. The fertile, child bearing years are the abnormality, she writes:

A sudden influx of hormones is not what causes 50-year-old Aunt Carol to throw the leg of lamb out the window. Improperly balanced hormones were probably the culprit. Fertility’s amped-up reproductive hormones helped Aunt Carol 30 years ago to begin her mysterious automatic weekly ritual of roasting lamb just so and laying out 12 settings of silverware with an OCD-like attention to detail while cheerfully washing and folding and ironing the family laundry. No normal person would do that—look at the rest of the family: they are reading the paper and lazing about like rational, sensible people. And now that Aunt Carol’s hormonal cloud is finally wearing off, it’s not a tragedy, or an abnormality, or her going crazy—it just means she can rejoin the rest of the human race: she can be the same selfish, non-nurturing, non-bonding type of person everyone else is.

“Rejoin[ing] the rest of the human race” is exactly right, in my assessment. I may have been a fist-raising feminist before surgery, but now my body has caught up to my beliefs.

These beliefs undercut religious and medical prescriptions to conform with behaviors that serve the patriarchal project of motherhood and all her attendant behaviors. Now I finally have the body chemistry to back these beliefs up.

Women may not yet be represented in scientific studies; treatments for menopause and every other female ailment under the sun may not yet be in development. But as women live longer, enter male-dominated fields (including medicine) in greater numbers and contest inequality—#metoo, #unequalpay, #girlslikeus, #rapecultureiswhen, #intersectionality, #everydaysexism, #effyourbeautystandards—a new post-reproductive idea of woman that doesn’t predicate femininity on fertility is emerging. By continuing to reimagine our roles in society, we can catch up with our bodies: independent, capable, beyond the confines of domesticated motherhood, perfectly enough on our own, thank you, normal.

***

Ann Neumann is author of The Good Death: An Exploration of Dying in America (Beacon, 2016) and a visiting scholar at The Center for Religion and Media, NYU.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.