A History of Sex Abuse in the Protestant Imagination

Protestant denominations also have structural abuse problems--and that isn't new.

Religion has a sex problem. In the twenty-first century, the problem has been termed a “crisis,” but the frequency of allegations of sex abuse in religious communities undermines the label. A “crisis” suggests a sudden and disturbing escalation. The long history of sex abuse in American religious congregations points instead to a persistent pattern.

Religion has a sex problem. In the twenty-first century, the problem has been termed a “crisis,” but the frequency of allegations of sex abuse in religious communities undermines the label. A “crisis” suggests a sudden and disturbing escalation. The long history of sex abuse in American religious congregations points instead to a persistent pattern.

Addressing the legacy of sex abuse in Catholicism, historian Robert Orsi suggests that we reject the label of “crisis” and call it “the Catholic normal” instead. Of course, Catholicism is not exceptional in requiring such nomenclature. Abuse has, for a long time, been “normal” in non-Catholic religious communities as well.

Just last year, the Houston Chronicle and San Antonio Express-News published a devastating report of sexual abuse within the Southern Baptist Convention—the largest Protestant denomination in the United States. In the last two decades, more than 700 victims have come forward with accusations against Southern Baptist ministers, church leaders, and volunteers.

Academic investigations confirm just how normal the “crisis” appears to be. A 2004 John Jay College study of sexual abuse of minors by Catholic clergy found allegations against 4,392 priests recorded between 1950 and 2002. That number makes up 4% of the entire U.S. priesthood. Likewise, a 2018 study of child sexual abuse in Protestant congregations analyzed 326 cases that led to the arrests of purported offenders between 1999 and 2014—a small fraction of the total sample of 2,240 allegations of abuse in Protestant congregations made between 1982 and 2014.

The figures are staggering. The stories are disturbing. And while there is nothing new about abuse in religious contexts, a look at its longer history suggests that Americans have only recently begun to think of the problem in their midst as abuse. As Megan Goodwin has shown in her series for the Revealer, the language of sexual abuse in the United States has most often been reserved for what she calls “American minority religions.” Protestantism in particular has largely escaped cultural associations with structural abuse. In fact, the words “sex abuse”—and any explicit mention of sexuality in general—rarely appeared in the press until well into the twentieth century. Before then, there had been other ways to mark certain religions as fraught with sexual danger. What language was used, by whom, and with regard to what religious communities had much to do with who had cultural power.

***

For a long time, U.S. Protestantism enjoyed the unspoken protections from accusations of sexual impropriety through its status as the religion of the majority. Whereas today’s media has become the public’s first point of contact in breaking stories of sexual abuse, the fledgling press of the 1830s (the decade that saw the birth of modern journalism) agonized about the limits of their craft’s subject matter. Their mandate was the preservation of public morals. To that end, most newspapers refused to publish material of morally questionable nature. Any story that happened to be about sex fell into that category and was often only alluded to in euphemistic tones and without genuine engagement—particularly when the stories involved Protestant pastors.

The one exception in the 1830s was Methodism. Its charismatic preachers, mixed-gender revival meetings, and anti-democratic English origins troubled the more established Protestant denominations of New England. Anglo-Protestants worried in particular about interracial mixing at the loosely supervised and highly emotional revivals as well as about what sexual behavior such close proximity could inspire. A contemporary critic warned that these revivals “produced more souls than they saved,” while Catholic missionaries noted that the meetings—with their dancing and twitching—constituted a scandal.

1833 print by Henry Robinson titled “A Very Bad Man” depicts Ephraim Avery and Sarah Cornell

So when the married Methodist minister Ephraim K. Avery was accused of seducing, impregnating, and murdering Sarah Maria Cornell, an unwed factory worker, in the winter of 1832, the media used the case as a kind of referendum on the morality of the Methodist establishment. Mainstream Protestant newspapers accused the New England Methodists of blatantly covering up the crime to protect the preacher.

When it came to Catholics, the press was more hostile still. In addition to the general spirit of nativism that characterized most newspapers at the time, several explicitly anti-Catholic publications sprung up to attack the “foreign religion.” The first of these weeklies, The Protestant, appeared in 1830. Its mission statement cut straight to the chase: “The sole objects of this publication are, to inculcate Gospel doctrines against Romish corruptions—to maintain the purity and sufficiency of the Holy Scriptures against Monkish traditions.”

Why would an entire publication need to besmirch the reputation of the Catholic Church? Americans were deeply concerned with the preservation of their young democracy. Having explicitly separated religion from the affairs of the state in the Constitution, Protestants were suspicious of Catholic allegiance to the foreign Pope. Anglo-Americans refused to believe that the despotic influence, which they perceived in Catholicism, would not spread to their fragile national politics and poison the minds of young people.

For outlets like The Protestant, prohibitions against deviant sexuality became a priority. To aid nativist propaganda and public denunciations of the Catholic Church, fictionalized first-person accounts and pamphlet exposés saturated the print market. Stories about sexual abuse and exploitation sold best.

The most sensational of these stories was Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk, a purportedly autobiographical narrative of a formerly Protestant woman who joined the Hotel Dieu convent in Montreal. Written like a gothic novel, Awful Disclosures is the tale of Maria Monk’s dramatic encounters with the abusive power of Catholicism. In the book, Monk first joins a Catholic school and later, as a young woman, becomes a nun herself.

Cover of Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk, 1836

In Monk’s retelling, upon joining the convent she gave up the right to her bodily autonomy. “I must be informed that one of my great duties was to obey the priests in all things,” Monk writes, “and this I soon learnt, to my astonishment and horror, was to live in the practice of criminal intercourse with them.” The euphemism “criminal intercourse” stood for coerced sex between nuns and priests. If nuns disobeyed, they would be locked in a cellar.

The most incriminating evidence of sexual exploitation were the babies born in the convent, who, according to Monk, were baptized and then immediately murdered—to conceal the evidence of the sexual encounters that produced them. Tying forbidden sex with infanticide helped Monk sell books and propagate the idea of Catholic moral perversion among Protestants who were already eager to believe such horrors.

In reality, Maria Monk likely never stepped foot in the Hotel Dieu convent. According to Monk’s mother, the bestselling author was a troubled young woman who had suffered a grave brain injury as a child. Escaping her troubles in Canada, she came to New York, where anti-Catholic Protestant pastors came to her aid, listened to her invented tale, and spiced it up in print—all in an effort to spread an alarmist story that would undermine the Catholic establishment.

Truth mattered little. Catholic convents were to be feared precisely because of their isolation from the world. Who could say what actually happened inside their walls?

The problem Protestants soon discovered in their own midst was that, walls or no walls, religion was fraught with sexual danger. Protestant ministers, it turned out, could be predators as well. They had seen this with Ephraim Avery in the 1830s. And by the 1870s, even the most mainstream ministers were showing signs of decay with regard to their sexual morality.

***

Henry Ward Beecher was the nineteenth century’s biggest celebrity pastor. Son of Lyman Beecher and brother to Harriet Beecher Stowe, Beecher had an almost genetic predisposition for fame. Eloquent, charming, and charismatic, Beecher preached “the gospel of love”—a theology rooted in grace and forgiveness, a milder version of the Calvinist Christianity of his forebearers.

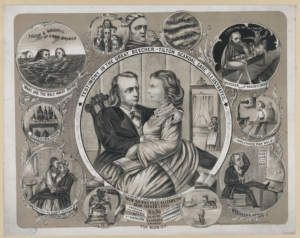

It turned out that Beecher may have been a little too loving with some of his female congregants. A contemporary rumor had it that Beecher preached to “seven or eight of his mistresses every Sunday.” In 1872, when rabble-rousing Victoria Woodhull—freethinker, radical, and the first woman to run for President in the U.S.—published an exposé of one of Beecher’s extra-marital affairs, Brooklyn’s favorite pastor fell into trouble.

Woodhull accused Beecher of sexual immorality with Elizabeth Tilton, the wife of Beecher’s long-time associate and friend Theodore Tilton. The pair had been awfully friendly—with pastoral home visits allegedly culminating in inappropriate touching. Theodore Tilton himself questioned whether the child Elizabeth was carrying was his. Was it fathered by Rev. Beecher—the very man who officiated the Tiltons’ wedding fifteen years earlier?

Letters of support for Beecher poured in, just as accusations against the minister spread in newspapers and on street corners. America was divided. Many Christians hinged their own salvation on the truth or falsehood of the accusations against their favorite pastor’s sexual morality. As one Protestant newspaper put it, “the Name which is above every name suffers by being dragged into the dust in the person of its representatives.” Through Beecher, God was implicated in scandal.

Worse, the Christian home—that sacred place that had been revered in the Protestant imagination—no longer seemed safe from the pernicious influence of seductive ministers. It did not matter that the Beecher-Tilton affair may have been entirely consensual; as a minister of the gospel, Beecher was entrusted with cultivating purity among his parishioners, not seducing them into adultery. As one reader of the Chicago Tribune put it, Beecher’s trial would ultimately establish whether “the minister of the Gospel, welcomed in utmost confidence to our families and firesides, and to the sick-chambers of our wives and daughters, be a scoundrel and a hypocrite, or not.”

“Testimony in the Great Beecher-Tilton Scandal Case Illustrated” by James E. Cook,1875

Beecher was ultimately found not guilty—both by his home congregation and by a hung jury in a civil suit—but the implications of Beecher’s potential adulterous appetites superseded the verdict. The first explosion of media scandals involving Protestant ministers coincided with Beecher’s 1875 trial, and these stories continued to escalate in volume and intensity through the last quarter of the century. Americans now wondered: Could female parishioners seeking spiritual counsel be subjected to their ministers’ impure desires? In learning the details of Beecher’s legal case, Americans discovered that even the most beloved of their ministers were susceptible to sexual sin.

After Beecher, preachers from all denominations were subject to allegations of sexual immorality—not yet called “sexual abuse,” but something approaching its contours. After the trial, the New York Times, bemoaning the hung jury, reviewed the Beecher affair and expressed hope that the case “may lead people in Brooklyn and elsewhere to distrust the new Gospel of Love, and to allow no priests or ministers to come between husband and wife, or to interfere with family ties or sully family honor.”

What troubled the Times was not Beecher’s apparent guilt, but the idea that religion might destroy the most sacred institution in American society: the family. This was a revolutionary assertion. Whereas nativist American writers had always depicted Catholic priests and polygamous Mormons as destroyers of families, it was not common to accuse Protestant ministers of such a corrupting influence. In 1875, Victorian family values were the norm; the figure of the Protestant minister was the de facto protector of the family. Henry Ward Beecher changed that. Protestant pastors’ morality was now suspect.

It is worth noting that even after Beecher’s sexual misbehavior, Protestant pastors’ misdeeds were rarely labeled “abuse.” A century after Beecher, Americans were still slow to identify the patterns of abuse that took place in religious contexts. It wasn’t until the 1980s that scientific studies and journalistic investigations of sexual abuse—and child abuse in particular—began to describe the problem in terms now legible to twenty-first century observers. Psychologists, criminologists, and journalists suggested that most abusers did not fit the stereotype of strangers with candy, but were instead most often people trusted by families—like male relatives. Or pastors.

Still, even in the 1980s, Protestant sex abuse had not yet reached the status of an epidemic; it remained episodic and context-specific, at least in the eyes of denominational leadership and the press. When Newsweek’s Kenneth Woodward and Patricia King put together a profile of clergy sexual abusers in 1989, they focused on clerical seduction that took place during pastoral counseling—not on other kinds of abuse. “Pastoral adultery is not the principal issue,” Woodward and King wrote, “Denominational officials are more concerned with local pastors who seduce congregants who rely on them for spiritual guidance and, in times of trouble, pastoral counsel.” Just as in the nineteenth century, “seduction” seemed to be the problem—not systematic abuse emboldened by unchallenged pastoral power.

All of which is to say that what we are dealing with today in discussions of religious sex abuse is both an old problem and a new phenomenon. The language of sexual danger has been used to decry certain religious expressions, to reproach the dangers of foreign ideas on account of alleged sexual immorality. It was not until the 1870s that Protestants began to recognize that their own religious communities—mainstream, established, and seemingly innocuous—contained within them the same dangers as the religious communities that seemed to them more foreign and fraught. And it wasn’t until the last three decades that we began to label the sex problem in our churches as “sex abuse” or understand the extent of the issue.

For a long time, Protestants took for granted the cultural protections afforded them by their brand of Christianity’s status as the de facto American religion. The time to reckon with the kinds of abuse this privileged position has enabled appears to have finally arrived. Inspired by #MeToo, the #ChurchToo movement has created spaces for survivors to speak out against the hierarchies that forced their silences and shielded their offenders. Even Billy Graham’s grandson, Basyle “Boz” Tchividjian, now believes that much of what Protestant churches teach (or refuse to mention) about sexuality enables abuse. “It’s sort of a perfect storm,” he said in 2017, “You have an ignorance about anything concerning sex, you have a view that men are in charge and have a higher degree of value, and you have a leadership structure that gives authority often to one person.”

For a long time, Protestants took for granted the cultural protections afforded them by their brand of Christianity’s status as the de facto American religion. The time to reckon with the kinds of abuse this privileged position has enabled appears to have finally arrived. Inspired by #MeToo, the #ChurchToo movement has created spaces for survivors to speak out against the hierarchies that forced their silences and shielded their offenders. Even Billy Graham’s grandson, Basyle “Boz” Tchividjian, now believes that much of what Protestant churches teach (or refuse to mention) about sexuality enables abuse. “It’s sort of a perfect storm,” he said in 2017, “You have an ignorance about anything concerning sex, you have a view that men are in charge and have a higher degree of value, and you have a leadership structure that gives authority often to one person.”

Whatever we call it—crisis, abuse, or the religious “normal”—this moment is different from past instances in that, perhaps for the first time, we are learning to listen to survivors. In the past, victims of pastoral abuse appeared in the press and in trial transcripts as secondary characters in the dramas of the important men whose reputations they challenged. Today, they are the protagonists of their own stories of resilience and grace. They do not always get the justice they deserve, but they are speaking out regardless. Perhaps the best way to understand the sex problem in our churches is not by debating its labels, but by listening to those it has affected.

It appears that there is nothing inherently safe about any denomination or culturally dominant religious tradition when it comes to sex abuse in religious communities. There are no neat correlations between safe theology and sound sexual practices, no assurances that those entrusted with the spiritual well-being of others will be good guardians of their bodies as well. If anything, the long history of protections afforded to Protestantism shows that even the most seemingly benign expressions of religious authority are laden with possibilities for tremendous damage.

Suzanna Krivulskaya is an Assistant Professor of History at California State University San Marcos, where she teaches courses in U.S. religion, sexuality, gender, and digital history. Her work has been published in the Journal of American Studies, Current Research in Digital History, and the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. She has also written for popular outlets like Religion Dispatches and Religion in American History. She is currently writing a book about the history of Protestant sex scandals and their coverage in the popular press in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.