A Black, Queer Woman Breaking from the White American Yoga Industry

A Review of Jessamyn Stanley’s Yoke: My Yoga of Self-Acceptance

(Jessamyn Stanley. Image source: Bobby Quillard and Jade Wilson)

In Jessamyn Stanley’s 2021 collection of autobiographical essays, Yoke: My Yoga of Self-Acceptance, she recalls taking a class with a popular white yoga teacher in North Carolina and feeling uneasy. His arms were tattooed with Sanskrit, the ancient Indo-European language of classic yoga texts like the Yoga Sutras. She found herself increasingly uncomfortable as he encouraged his students to see themselves as part of a South Asian lineage of Classical yoga.

Stanley’s first book, Every Body Yoga, had just come out. She had made a name for herself as a “fat, Black, queer yoga teacher in a predominantly thin, White, and very straight yoga industry.” And she was growing increasingly uncomfortable with how white Americans—including the tattooed man leading this workshop—had taken up yoga.

Stanley found the courage to raise her hand. She knew she would likely be the sole dissenting voice in the room. When she had called out cultural appropriation and the lack of South Asian representation in her earlier yoga teacher training, none of the other trainees saw it as a problem. Stanley told the group she did not see herself as a Classical yoga practitioner. The teacher smirked, and told her that if she did not feel a connection to Classical yoga, it was because she did not know enough about the practice.

As Stanley writes in Yoke, “Classical yoga, the Vedas, and Sanskrit are rooted in South Asian culture, with particular connective tissue in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, among many other faiths.” For her, the teacher’s approach to yoga not only appropriated South Asian traditions, it also erased Stanley’s Black American lineage: “it made me feel as though I was being told to steal someone else’s cultural identity and nullify my own.”

When she walked out of the workshop, Stanley broke from what she calls the white American “yoga-industrial-complex.” For her, yoga in the U.S. is inextricably bound up in the country’s history of racism, capitalism, and settler colonialism. In Yoke, she grapples with the contradictions of practicing a South Asian tradition on U.S. soil, and she creates a spiritual practice of yoga that is uniquely her own.

***

The title of Stanley’s book, Yoke: My Yoga of Self-Acceptance, references two things: 1) yoke, a Sanskrit word that connotes union, and 2) a typo in her first book. Following the publication of Every Body Yoga, a reader wrote to inform her that “yoke” appears erroneously as “yolk,” conjuring images of a runny egg rather than divine union. This typo sent Stanley into a tailspin of self-doubt and insecurity. She questioned her legitimacy as a public voice in yoga, a relatively new practitioner who rose to popularity as she chronicled her yoga poses on social media.

The title of Stanley’s book, Yoke: My Yoga of Self-Acceptance, references two things: 1) yoke, a Sanskrit word that connotes union, and 2) a typo in her first book. Following the publication of Every Body Yoga, a reader wrote to inform her that “yoke” appears erroneously as “yolk,” conjuring images of a runny egg rather than divine union. This typo sent Stanley into a tailspin of self-doubt and insecurity. She questioned her legitimacy as a public voice in yoga, a relatively new practitioner who rose to popularity as she chronicled her yoga poses on social media.

Stanley’s self-doubt resonated strongly with me. I used to perform kirtan, a South Asian devotional musical tradition. The band I worked with often performed in yoga studios and ashrams, leading call-and-response Hindu devotional songs with primarily-white audiences. Like Stanley, I encountered many white yoga practitioners who took on Indian names, wore South Asian fashion like saris and bindis, and adopted India as a spiritual homeland. And like Stanley, I felt insecure about my own legitimacy to call attention to the white entitlement that drives this behavior (in my case, I am half-Indian, born and raised in the U.S., and cannot neatly claim a “South Asian” identity).

By claiming South Asian practices as their own, Stanley argues, white Americans avoid dealing with the shame of their ancestors’ racist legacies. Rather than argue that people of color should feel as empowered as white people to adopt Classical yoga, Yoke contends that a deep practice of yoga can bring each of us closer to our own cultural and spiritual traditions. Some Black yogis, for example, practice Kemetic yoga, which traces its roots to Egypt. For Stanley, however, the practice of yoga has facilitated a process of personal reflection on her “very Black, very Southern, and exceedingly American” roots.

In Yoke, we learn what this lineage means to Stanley. She is a third-generation Bahá’í who left the religious tradition when she came out as queer and started to question the tradition of celibacy before marriage. In the years that followed, she carved out her own spiritual tradition. Along with yoga and meditation, her amalgam of spiritual touchstones has included tarot, marijuana, astrology, crystals, and the writings of James Baldwin, Malcolm X, Gary Zukav, Don Miguel Ruiz, Henry David Thoreau, Swami Vivekananda, Dr. Maya Angelou, and Kendrick Lamar, whose album good kid, m.A.A.d city is her favorite yoga soundtrack: “He and I don’t have the same story, but in his authentic truth I hear my own. And when I hear his music during my practice, I find my way back to myself.”

***

Stanley locates the problem of white yoga appropriation in American yoga’s hyper-focus on asana, or physical postures. Anyone who has attended a yoga class in the U.S. is familiar with asana, which may include sun salutations, body-pretzeling twists, and head stands. American yoga classes also typically touch on pranayama, or breathwork, though the focus is primarily on asana. In Classical yoga, asana is done in tandem with pranayama to prepare the body for meditation.

The American yoga market’s focus on asana has influenced Stanley’s career as a yoga teacher. She offers an important representation for those who felt alienated in majority-thin, white, straight yoga classes. And her physical strength and dexterity inspire those who were also trying to practice yoga at home, outside the “yoga-industrial-complex.” When I started following her account in 2016, I took screen-shots of her headstands as inspiration for my own practice.

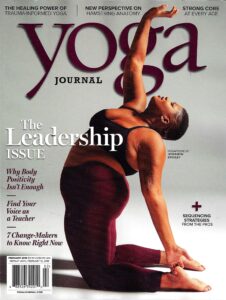

Stanley aspired to be on the cover of Yoga Journal, one of the longest-running American yoga magazines. When she was invited to pose for the cover, it taught her that Yoga Journal was actually part of the “yoga-industrial-complex,” and her goal of being on the cover was tied to her desire for “mainstream acceptance (aka white acceptance).” In the end, Yoga Journal ran two covers—one featuring Stanley, the other featuring thin, light-skinned Yoga Works founder Maty Ezraty. Stanley felt her body had been tokenized, and that the magazine had run a double-cover because they were worried hers would not sell.

Stanley aspired to be on the cover of Yoga Journal, one of the longest-running American yoga magazines. When she was invited to pose for the cover, it taught her that Yoga Journal was actually part of the “yoga-industrial-complex,” and her goal of being on the cover was tied to her desire for “mainstream acceptance (aka white acceptance).” In the end, Yoga Journal ran two covers—one featuring Stanley, the other featuring thin, light-skinned Yoga Works founder Maty Ezraty. Stanley felt her body had been tokenized, and that the magazine had run a double-cover because they were worried hers would not sell.

Stanley sees these spaces of profit-driven hyper-visibility—from Instagram to Yoga Journal—as contradicting the deeper spiritual lessons of yoga: to transcend mind/body dualism on a path towards spiritual enlightenment. Transcending mind/body dualism, for Stanley, means letting go of how the world encourages us to see ourselves. “Who are we,” she asks us, “when our definitions of who we are fall away?” Stanley refers to the yogic sense of selfhood as a “subtle body” that encompasses our full, spiritual selves. In other words, yoga can help us connect with a sense of selfhood that is not bound by worldly definition.

For Stanley, accessing the “subtle body” has helped her heal from trauma. In Yoke, she bravely chronicles experiences with sexual assault, and how meditation has allowed her to feel a difficult range of emotions: “my shame and my anger and my sadness and my frustration and my guilt and my malice and my vindictiveness and my hatred and my bloodlust and my grief.”

Unfortunately, in the “yoga-industrial-complex,” Stanley argues that this spiritual sense of selfhood becomes a tool to avoid difficult questions about oppression. If our definitions of who we are fall away, then what happens to race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, and size? Stanley’s writing reminds us that the rhetoric of connection and spiritual transcendence in American yoga studios too often masks the straightness, whiteness, and gender normativity of these spaces.

***

The context of the “yoga-industrial-complex” shapes not only how Black yoga practitioners interface with white American yoga spaces, but also how Black and South Asian people engage each other around questions of cultural appropriation and social justice.

In Yoke, Stanley recounts participating on a panel on cultural appropriation alongside a South Asian DJ who blends bhangra and hip hop. Stanley was prepared for the DJ to accuse her of cultural appropriating yoga from its South Asian roots. Instead, the conversation was a generative one, and it led Stanley to reflect on how both Black and South Asian people are “permanently affected by our collective history of white supremacy.”

Debates about yoga in recent years have focused not only on white supremacy, but also on the role of yoga in upholding caste discrimination. For example, at the height of the summer 2020 anti-racist protests, I joined a march in New York City and walked alongside a Black abolitionist activist. She recounted how her organization had tried to make yoga mats and classes accessible to incarcerated women. South Asian activists criticized the Black and Latinx organizers and drew attention to yoga’s complicity in caste and religious oppression in South Asia.

In recent years, the ruling Hindu party in India has taken up yoga as a way to push for global legitimacy through celebrations like “International Yoga Day,” which was formally adopted by the United Nations in 2015. South Asian organizers have drawn attention to the fact that dominant-caste Brahmins claim Sanskrit as a holy language that should not be spoken by those in marginalized castes. The language’s widespread use in white yoga spaces is thus not solely cultural appropriation, but also a replication of caste oppression.

This South Asian activism has shaped Stanley’s perspective on Sanskrit, even since the book’s release. In Yoke, she argues that we should “Respect the books. . . . Respect the history of Sanskrit. Respect South Asian culture.” However, in an interview following the book’s publication, she reports grappling with the language: “Sanskrit has been used in South Asia to control people and that it has become this whole issue of class and caste. It’s so deeply wrapped up in South Asian heritage and culture.”

The people who have pushed Stanley to rethink the politics of Sanskrit have done so out of an awareness of the economic links between the way yoga impacts marginalized people in both the U.S. and India. Yoga studios are often harbingers of gentrification that displace working-class and communities of color in the U.S. Likewise, in India, the government expropriates land from indigenous peoples for yogic leaders. The “yoga-industrial-complex,” in other words, is a transnational phenomenon that extends beyond American yoga.

***

In addition to greater awareness of yoga’s role in sustaining systems of marginalization, Stanley’s future writing could also engage more closely with allegations of sexual assault leveled at her primary reference point for yogic philosophy, Swami Satchidananda. Quotes from his translation of The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali precede each of her chapters. Born in Tamil Nadu, India, Satchidananda traveled to New York in the 1960s and founded his first yoga studio in the U.S. in 1970. He was opening speaker at the Woodstock Music and Arts Festival in 1969 and played a central role in popularizing yoga in the U.S. Stanley could extend her important reckoning with the #MeToo movement to engage with South Asian yogic leaders, many of whom have profited from the “yoga-industrial-complex.”

Yoke offers a useful framework for holding these difficult truths in tandem. By sharing the struggle to see herself whole–trauma, contradictions, and insecurities included–Stanley invites us not only to do the same with our own selves, but with yoga itself. In future writing, she has an opportunity to extend her critique of the “yoga-industrial-complex” to the complicated transnational contexts that yoga inhabits.

Vani Kannan is an assistant professor of English at Lehman College, CUNY.