A Baby at the Shiva

A review of the film Shiva Baby and its focus on Jewish culture, sexuality, and tense family expectations

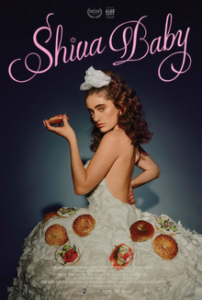

(Rachel Sennott as Danielle in Shiva Baby)

The thing about Shiva Baby’s main character, Danielle, is that she’s not that nice. She’s petulant to her parents who ask her to come to a shiva (post-funeral Jewish mourning visit); she’s defensive to her ex-girlfriend Maya who is unexpectedly at the shiva and wants to reconnect; she’s petty to her parents’ friends who keep grabbing her cheeks, her clothes, her waist (“you’ve lost so much weight,” they say passive-aggressively); she’s downright rude to Kim, the sleek shiksa (non-Jewish) goddess who offers her a job. (“I’m not really into that girl-boss thing,” Dani sneers to Kim’s face.) And yet, she is utterly gripping. In this serpent coil of a film where every minute tightens the tension even more (and more, and more, to the point where the audience is about to break, let alone Dani herself) we can’t keep our eyes off of her. The film is enthralling partly because actor Rachel Sennott is brilliant in the lead role. But the main reason the film captivates is because Dani is familiar – for American Ashkenazi Jews, and for everyone who has ever encountered a stereotype of them.

While wildly different in post-millennial ways, Shiva Baby might remind viewers of Seinfeld or Curb Your Enthusiasm. The whole set-up is an engaging combination of what people think they know about Jewish community and rituals and how Judaism actually works on the ground. As skin-crawling and uncomfortable as the entire “running-into-your-sugar-daddy-and-also-your-ex-girlfriend-while-comforting-mourners-with-your-anxious-parents” situation is, it’s also as comfortable as lox and cream cheese, intrusive relatives and squabbling parents, awkward exes and secret relationships – with a siddur (prayerbook), a hot rabbi, and a kaddish (mourning prayer) thrown in. The film both is and is not like your bubbe’s (grandmother’s) shiva (“poo poo poo god forbid.”)

Shiva Baby is 77 minutes of tension chronicling Danielle’s worst-ever day in the company of everyone her parents have ever known. It’s horror cringe comedy with Yiddish and bagels and a rabbi who looks like “Robert DeNiro and Gene Kelly had a Jewish baby.” Limping along toward her college degree in, as her mother predictably says, “something-gender-something-self-constructed,” it turns out that Dani has a side hustle to pay the bills, and it’s not, as she’s been telling her parents, babysitting. Well, not exactly. Dani rushed to the shiva from a sugar daddy date; her hair is less perfect than she’d like (and gets progressively frizzier throughout the film) and the contrast between the agency she exercises in her sex work and the grouch adolescent she immediately becomes in her parent’s home is stark. Dani’s failure to live up to her parents’ ideal, let alone her own, is underscored at the shiva when we see Dani with her successful ex-girlfriend Maya, there in all her straight-haired, law schooled glory. Of course, the last thing Dani wanted to do was bump into her ex-girlfriend at the shiva of someone she’s not even sure she knew. Scratch that: it’s the second-to-last thing she wanted. The last thing she wanted was to bump into her sugar daddy, an older man who secretly pays her for the pleasure of her company, intimacy, and body.

Shiva Baby is 77 minutes of tension chronicling Danielle’s worst-ever day in the company of everyone her parents have ever known. It’s horror cringe comedy with Yiddish and bagels and a rabbi who looks like “Robert DeNiro and Gene Kelly had a Jewish baby.” Limping along toward her college degree in, as her mother predictably says, “something-gender-something-self-constructed,” it turns out that Dani has a side hustle to pay the bills, and it’s not, as she’s been telling her parents, babysitting. Well, not exactly. Dani rushed to the shiva from a sugar daddy date; her hair is less perfect than she’d like (and gets progressively frizzier throughout the film) and the contrast between the agency she exercises in her sex work and the grouch adolescent she immediately becomes in her parent’s home is stark. Dani’s failure to live up to her parents’ ideal, let alone her own, is underscored at the shiva when we see Dani with her successful ex-girlfriend Maya, there in all her straight-haired, law schooled glory. Of course, the last thing Dani wanted to do was bump into her ex-girlfriend at the shiva of someone she’s not even sure she knew. Scratch that: it’s the second-to-last thing she wanted. The last thing she wanted was to bump into her sugar daddy, an older man who secretly pays her for the pleasure of her company, intimacy, and body.

Dani got both, served with a side of rugalech (which shiksa goddess Kim calls “aruglah” and don’t think everyone didn’t notice and mock her), gossip, actually-not-well-meaning-advice, passive aggressive compliments about how thin she has become, and plenty of questions about what she is going to do after finishing a degree in Gender Studies. Like any Jewish daughter knows, the key to surviving these questions is lying, best with the help of a parental accomplice. Dani’s mother, a mash-up of every Jewish mother stereotype in one (to the point where maybe it’s a little painful, and definitely way too much), agrees (and okay maybe she suggests it), that they develop a “sound-bite” (Dani’s words) about all her upcoming job interviews and prospects. Of course, Dani is lying to her mother and father about her sex work, and her mother and father are lying to themselves about her bisexuality.

Soon after arriving to the shiva, Dani’s mother cautions her against any “funny business,” which we learn is code for queer intimacy. To her parents, Dani’s relationship with Maya was fine for high school, a shenanigan like studying gender or taking time off before law school. It’s not “real,” and it’s best left behind. Here we see both a denial of bisexuality as a “phase” and a deeper struggle with ambiguity: while progressive Jews have long supported gay marriage and LGBTQ rights, there is still a strong emphasis among American Jews to settle down with one person and to raise Jewish children, with a side of “gay relationships are fine for everyone else’s kids.” Dani’s mother would likely be horrified by homophobia in other people. But when it comes to her daughter, she is still waiting for Dani to settle down with a nice Jewish boy. Or maybe a nice Jewish girl, if she were forced in to it. But one or the other already, and really, a boy.

(Dianna Agron in Shiva Baby)

The film is filled with intertextuality: #actuallyJewish actress Dianna Agron, famous for her role as Quinn Fabray on Glee, has made a career playing shiksa princesses, a role she revives here with a wink of her perfectly naturally made-up eyes. A maybe-jealous Maya describes Kim as “Malibu Barbie;” a definitely jealous Dani responds that she’s “basic, generic, boring.” Kim is the outsider here, and she knows it, and she’s knows something is up with Dani but she can’t possibly guess what. Or can she? She knows for sure that Dani is no babysitter, but it’s not clear if she knows that Dani is actually a (sugar) baby with her husband.

Kim seems perfect, but she doesn’t know what to call things and she’s doesn’t know not to bring a baby to the shiva. (Though for the record I’ve been to plenty of shivas with babies: it’s fine, as long as they are quiet. This one wasn’t.) Dani’s getting everything wrong in her life, but she knows how to do a shiva right. She knows where to stand and when to get food and who to help and even to kiss the siddurim (prayer books) when they fall, though perhaps she doesn’t need to kiss them quite so slowly and one-by-one. Kim and Dani are both sides of the same coin: one messy, with brown curly hair that frizzes, and one with perfect long blonde hair and perfect skin and perfect clothes and a perfect job and a perfect life. Except both are sleeping with the same man, and he is lying to everyone.

But so is Dani. She’s lying to her parents about where she gets her money. She’s lying to Max, the sugar daddy she bumps into at the shiva: she’s not actually saving money for law school tuition. She’s lying to Maya: she doesn’t actually remember whose shiva it is (Uncle Morty’s second wife’s sister, for the record) and she isn’t really sad about that woman’s death. And she’s lying to herself: she misses Maya and she misses community and really, she doesn’t have anything figured out at all.

And it’s her messiness that ultimately makes her tolerable. She’s panicking, and she’s in pain, and she’s spiraling, and she’s losing. She’s losing her grip, and she’s losing the fight. We all know – now more than ever – what it means to lose our grip and lose the fight. We all know – now more than ever – what it means to sit in ever increasing tension and just let go with one long scream.

There’s no happy ending in this film, no nicely resolved package, but there are small moments of tenderness and love, and even, in the horror show that is the shiva itself, there is one long steady stream of care. Every pinch of the cheek, every wipe of schmutz (dirt) off her punim (face), even every intrusive question about jobs and futures and weight and love is a way of showing care, of taking care, of giving care. Dani rejects it with her abrupt answers and her insincere smiles and her offers of help designed to let her escape. But she also rejects it all because she can: these people, she knows, may – nay will – gossip about her behind her back (and to her face) and boy will her mother hear about it the next day, but they will all still be there.

I wouldn’t say that’s the enduring message of the movie, or even its goal. Originally a short film, Shiva Baby plays like a carefully constructed and tightly plotted stage play, with mounting tension and no breaks or relief. It could be too much at the 77-minute running time, but it works, partly because of the excellent acting and partly because the cultural stereotypes (which, for some, are especially familiar) provides a kind of comfort that serves to break it up. We may not know Dani or Maya or her parents, but we’ve seen them depicted before. And that might be a bit lazy and it might flit with some misogynistic tropes of the overbearing Jewish mother and the emasculated Jewish father; yet still, it works. We don’t quite laugh when Dani’s parents eye the crowd hungrily looking for who they know who might know someone who can give Dani a job. But we do roll our eyes knowingly, because of course that’s exactly what we imagine someone’s overbearing, squabbling, supportive, stereotypical Jewish parents would do at a shiva, along with whipping out photos and being embarrassing about sex in some way or other. Like the pithy quip that Catholics never talk about sex but are always having it; Jews, as the joke goes, are always talking about it (remember – Freud was Jewish!) but are never actually having it.

While the film gets a few things wrong about Jewish ritual life, it isn’t really a film about mourning rituals, or mourners at all. We don’t see the low-to-the-ground chairs that the principal mourners typically sit in, which would be rented from the funeral home and brought in a handy shiva-in-a-box kit along with a candle that burns for the duration of the shiva. We can’t tell if the mourners’ clothing is ripped or if they are wearing a ripped ribbon, but it is almost certainly the latter; ripping actual clothing (which would then be worn the entire week) is becoming increasingly rare outside of the Orthodox world. Indeed, much of the shiva rituals are designed to remove the obligation to vanity: principle mourners traditionally don’t greet guests, serve as hosts, prepare their own food, or worry about their appearance. But in the film, as is increasingly common, the mirrors remain resolutely uncovered, as we learn in a pivotal scene in the bathroom that hinges on Dani looking at her own reflection. Vanity, the film seems to say, is still very much present in this space.

Despite its name and the proliferation of people Dani has slept with, Shiva Baby is not a particularly erotic film; the specter of sex is more sketchy than sensual. But it is central. Dani’s parents play out a particular version of Jewish sexuality, with the anxious mother and the passive father and endless squabbling and love. If they are the boomer version, Dani’s the zoomer: a gender-studies-sex-worker-bisexual-lost-soul. But even as Dani and her mother are different, both women share anxiety and an aching awareness of how they appear to others. Dani’s bisexuality is a sticking point only insofar as it highlights her failed relationships and her search for connection; while there is a clear pressure on Dani to conform, of which heteronormativity is a part, her sex work is likely more problematic for her parents than her queerness. After all, her relationship with Maya wasn’t a secret to them or anyone else at the shiva, even if they refuse to accept it as meaningful. Which, in a way, Dani herself also refuses to do until, in the most touching scene of this not-particularly-touching film, Dani and Maya embrace, and we see, for the first time, Dani uncoils.

Well, maybe for the second time in the film. The first time is when Dani gives in to her – and the audience’s – impulse and begins to scream. We are all, in a way, waiting for it. But when it comes, it is no kind of release. That’s the thing about family and ritual and community and the people who have known you all your life: in the best-case scenario, even when they exacerbate everything you struggle with, they are there. They will offer you a lift home, albeit with your ex-girlfriend and your sugar daddy and his wife and baby crammed into a messy minivan. There is no release. But these kinds of family moments form their own kind of ritual within the larger life-cycle events that create and sustain community, Jewish or otherwise. And in that too can be comfort, even when it is challenging: you know exactly what to expect the next time you bump into your sugar daddy at a shiva: bagels and lox and pinches on the cheek and job offers and a siddur to kiss. And maybe a baby, if a shiksa goddess accidentally brings one to the shiva.

Sharrona Pearl is Associate Professor of Medical Ethics at Drexel University. Her most recent book is Face/On: Face Transplants and the Ethics of the Other. You can find clips of her freelance writing at www.sharronapearl.com.