Wrestling with Jewish Shame

A Review of Sarah Hurwitz’s book “As a Jew”

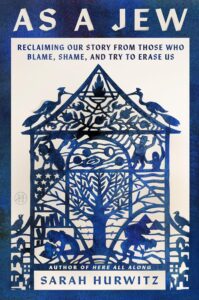

(Image source: Design by Rachel Zhang)

The subtitle of Sarah Hurwitz’s new book As a Jew: Reclaiming Our Story from Those Who Blame, Shame, and Try to Erase Us indicates that she invokes “As a Jew” to celebrate Judaism and to eschew any shame-filled disclaimers. Hurwitz compellingly and unsparingly includes her own former and present self in this meditation on Jewish shame: she readily admits that, out of ignorance, she was one of those Jews who routinely used all sorts of disclaimers to present herself as an acceptable Jew in a Christian-centered culture with a long history of antisemitism. Hurwitz’s As A Jew is part memoir, part history, and part polemic determined to say goodbye to all that Jewish shame.

As a Jew is, in many ways, a continuation of and sequel to Hurwitz’s Here All Along. In that earlier volume, Hurwitz, who was a speechwriter for Michelle Obama, recounts her reconnection to Judaism as an adult and writes a Judaism primer. If that book had only included her engaging summary of the Torah, it would have been enough; happily, there’s much more there about the Jewish calendar and Jewish lifecycle events, especially rituals around death. And she unpacks Jewish conceptions of God, emphasizing that “other than monotheism, there is no universally accepted Jewish creed or article of faith defining the Divine.”

While Here All Along was a “love letter to Judaism,” As A Jew seeks to explain why Hurwitz and so many others have become so disconnected from Judaism that they define themselves as cultural or secular Jews or social justice Jews without knowing much or anything about Judaism’s take on social justice. Her answer, taken from the annals of history and the contemporary moment, is bracing.

While Here All Along was a “love letter to Judaism,” As A Jew seeks to explain why Hurwitz and so many others have become so disconnected from Judaism that they define themselves as cultural or secular Jews or social justice Jews without knowing much or anything about Judaism’s take on social justice. Her answer, taken from the annals of history and the contemporary moment, is bracing.

Her path to that answer started when she became a chaplain. Hurwitz was profoundly moved by those who cared for her grandmother while she lay dying and by the role chaplains played during the pandemic. After learning that volunteer hospital chaplains don’t have to be clergy or Christian, Hurwitz decided to take chaplaincy education classes. That training illuminated the many ways contemporary culture is so drenched in Christianity that it can’t recognize Jewish difference. Her chaplaincy training assumed that the keys to the life of the sacred were belief, obedience, spirituality, and religion. However, she realized that such keys were the wrong ones for Jews and Judaism. Rather, she views Jews not primarily as a religious group but as a people who have a covenant or partnership with God, with whom they argue a lot of the time. They must do things rather than simply believe things. Indeed, the notion of a Jewish atheist who selectively follows commandments as a performance of their peoplehood is not at all oxymoronic as it would be to most Christians (notably, there are 613 commandments, so by necessity, even the most observant Jews can’t do the whole 9 yards!)

For Hurwitz, the Jewish textual tradition is a well of wisdom that connects Jews throughout the ages. She understands the Torah as a form of protest against and holy separation from the empires of the time. Just as importantly, Jews extend the five books of Moses through the Talmud and in ongoing commentary through the ages, so that Jews “are all part of the same story—one rooted in our texts and expressed in all sorts of ways in our lives.” Such rootedness in a shared, diversely interpreted textual tradition leads her to endorse Amos Oz and Fania Oz-Salzberger’s formulation that Jewishness “is not a bloodline but a textline.” According to Hurwitz, “Our texts are the one thing Jews have carried with us throughout our journey, with each generation adding its own pages. Those words, I think, are our shared DNA. Being part of that story, and continuing to tell it—that, I think, is what makes us Jews.”

Discovering that the keys to her house were different than the ones proffered by the dominant Christian culture partially explains how she and so many Jews become alienated from Judaism: they are given the wrong keys and thus have trouble getting into or living in their Jewish homes. And the process of unlocking these doors for herself and others (including and especially non-Jews) quickly turns into an obstacle course. When she points out to one of her chaplaincy supervisors that certain forms of prayer being touted as universal are more associated with Christianity and might make Jewish hospital patients uncomfortable, her supervisor doubles down on her universality claims. While Hurwitz strived to remain polite, she acknowledges that her patience was tested: “I would do my best to restrain myself from shouting, ‘Are you kidding me with this? Not only am I Jewish, but I have literally spent thousands of hours learning about Judaism and writing a book about it.’”

As Hurwitz demonstrates, Christians telling Jews who they are and what they believe rather than letting Jews speak and believe for themselves is part and parcel of Christian anti-Judaism. As Hurwitz points out, Christians have used Jews for millennia as witnesses for Christianity: Christians interpret the Hebrew Bible as being about the life and theology of Jesus, and Jews continuing their textual tradition in the form of the Talmud and beyond is seen as a threatening challenge to supersessionism, the belief that Christianity supersedes or replaces Judaism. In order to meet this challenge, Jews have to be portrayed not as theologically different from Christians but as wrong. Such wrongness morphs into anti-Judaic thought that obsesses on “Jewish power, depravity, and conspiracy.” That unholy trinity becomes a through line from charges of Deicide and Host desecration to the Inquisition to massacres, pogroms, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and ultimately the Shoah and anti-Zionism. Some might be tempted to view antisemitism as a contemporary phenomenon that culminates in the Holocaust or to opine about the mystery of Jew-hatred. But Hurwitz argues that the supposed mystery of antisemitism is not a mystery at all but rather is clearly rooted in Christian anti-Judaism. And that Christian tradition has been imported into the Muslim Middle East, a process aided by Arabic translations of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in the 1920s and by Nazi propaganda in the 1930s and 1940s.

While Emancipation and modernity ameliorated Christian antisemitism, those forms of progress became a double-edged sword: on the one hand, they enabled legal, economic, and cultural mobility for Jews. On the other hand, they induced Jewish shame and encouraged, if not required, Jewish citizens to leave behind some of the keys to their ancestral tradition that were not shared by their non-Jewish fellow citizens. Jewish law often seemed irrational and at odds with the norms of the nation-states in which Jews lived. In order to conform, reformers redefined Judaism as “a religion of prophetic morality, not Talmudic law.” Cacophonous prayer went out of fashion; to emulate the “decorum” associated with Christian services, worshippers listened silently and responded in unison, services included organs and choirs, and Hebrew was no longer the lingua franca. The price of citizenship seemed to entail a major makeover of Judaism. For Hurwitz, the loss of the Jewish textline for all but the most observant Jews is the most grievous because it relegates Jewish wisdom and Jewish values to the dustbin of history.

In sharp contrast to her earlier book, Hurwitz does a full wrestling match with Zionism and Israel, and in the process writes herself out of feeling shame about the Jewish state. Her approach is a breath of fresh historical, political, and empathetic air. Going into her research, she expects to find a country steeped in original sin; instead, she finds herself face to face with a “founding story no worse than that of countless other countries” and “contending with the torturous complexity of an intractable conflict.” Hurwitz defends Israel’s right to exist even as she recognizes the ludicrousness of being forced to do so. Her historical overview of this conflict is admirably regional—she chronicles the ways that Britain as well as Egypt, Jordan, and Syria played political football with Palestine to the detriment of both Palestinians and Israelis. And she refutes the notion that Israel maps onto the model of European colonialism: Israelis had no empire that they were trying to expand through the acquisition of resources or a civilizing project.

Even as she argues that Zionism has become the new “Jewish question,” Hurwitz refuses to deny Palestinian suffering or defend indefensible Israeli policies. She recognizes that there are two peoples who “have a right to live in peace and security in this land”; she recognizes that “Israel bears plenty of responsibility for the current conflict, particularly with the rise of the right-wing, religious settler movement in the wake of the 1967 war”; and she takes Netanyahu to task for weakening moderate Palestinian politicians while indirectly strengthening Hamas. She also recognizes Jewish terrorism against Palestinians as a form of “fanaticism” that is “a sickening distortion of Jewish tradition and a cancerous growth on the Zionist dream.” She takes seriously the tragic plight of Palestinians without falling into “nonchalance about the lives of seven million Jews in Israel.” When Hurwitz identifies the wisdom of the Jewish textline, she includes its tendency to “speak not in dogma, but in dialogue.” In her stalwart but non-dogmatic discussion of Zionism and Israel, Hurwitz admirably inscribes herself into that textual tradition.

The contemporary antisemitic moment is a fraught one for Hurwitz and for many Jews, and she brilliantly gives voice to her worry about worrying: “Is my distress over knowing the worst parts of Jewish history stopping me from thinking clearly about the present? Or is knowing the worst parts of Jewish history forcing me to think clearly about the present, and is that causing my distress?” Yet her achievement in As a Jew is to turn the worst parts of the Jewish past and present into an empowerment narrative. Rather than falling prey to playing the victim Olympics, she compellingly argues that we need to understand the antisemitic stories that others tell about us because such stories prevent us from freely choosing Judaism.

For Hurwitz, a free Jew is necessarily a knowledgeable Jew, and she castigates her younger self for her intellectual arrogance: “I’d concluded that thousands of years of Jewish tradition amounted to little more than what I’d learned in Hebrew school, and I dismissed it accordingly. I would never dream of treating anyone else’s cultural, ethnic, national, or religious heritage that way.” Culturally programmed Jewish shame aided and abetted such a double standard. Hurwitz finds freedom via studying the Jewish textline and its plurality of voices, and she seeks to share her journey and the fruits of her labor. In Jewish study, she finds an alternative to a social media landscape that encourages “toggling between ‘how dare they think that?’ self-righteous outrage and ‘yes! Preach!’ triumphalism.” Jewish tradition, inextricably connected to her chaplaincy work, teaches her that we have “to get right up close to people in moments when they are suffering, to be radically present with them” when they are ill or death is imminent. Jewish tradition teaches her to embrace her people and “to live proudly, gratefully, and joyfully—as a Jew.” And if such a way of living and being is uncool, so be it.

Helene Meyers is Professor Emerita of English at Southwestern University. Her most recent book is Movie-Made Jews: An American Tradition.