Building Resistance: On Church, Space, and Crisis

The coalitions that were able to come together during the AIDS epidemic because a queer church owned its own building

(Image source: Trudie Barreras/MCC Archival Collection/Q Spirit. A watercolor of the MCC church at 150 Eureka St.)

This is a story about a building, a small, funky, church building located at 150 Eureka Street in San Francisco. It was built in 1902 atop a small river on a residential street. As the building expanded to fill the lot, it abutted the two neighboring houses. It’s in a working-class area that became a gay neighborhood, in a city rumored to be unreligious but also known as a spiritual playground, with communities for seekers of all types. When it was first built, 150 Eureka Street housed a Baptist congregation and, later, a Pentecostal one. In 1979 it became home to the Metropolitan Community Church of San Francisco (MCC-SF), an LGBTQ identified congregation. In 2015 it was sold to developers, and in 2025 four boutique condos at 150 Eureka Street sold for an average of $2,166,250 each.

This is also a story about a community that gathered in 1970 to resist the twin notions that God hates gays and lesbians and that queer people couldn’t, or shouldn’t, be religious. And it’s about how that community faced one of the most significant public health crises of the 20th century: HIV/AIDS. It’s about the kinds of resistance that can grow when groups have the physical space to cultivate it. And it’s about what’s possible, materially and psychically, when marginalized groups create spaces of their own—buildings and communities that become laboratories for ritual, social, and political experimentation and change.

***

The first gathering of MCC-SF took place in April 1970 in the social room on the second floor of Jackson’s, a popular gay bar. “They called it the Penthouse,” MCC-SF’s first pastor, Howard Wells, recalled in a later sermon. “We called it the Upper Room” – a reference to where Jesus’s last supper with his followers was held. In San Francisco, LGBTQ people owned and operated many of the city’s queer bars and clubs, which wasn’t always the case in other places. These “pockets of queer association and camaraderie,” according to historian Nan Amalia Boyd, were “the roots of queer activism,” the foundation on which residents were able to build LGBTQ political organizations and queer cultural institutions—like queer churches.

Throughout the 1970s, the church grappled with the problem of finding the right space. In its early years, MCC-SF rented a downtown commercial property that served as a community center. Folks could drop in any time, get support, and worship with the congregation on Sunday mornings. Sunday evening services were held in church buildings around the city owned by supportive mainline Protestant congregations. One of the first was located up a steep San Francisco hill. When looking for their next location, the church focused on finding a more accessible space.

In 1972 MCC-SF started meeting at Stewart Memorial Presbyterian Church in the city’s Mission District and rented the church’s parsonage for their offices. They had hopes that this would be their long-term home. But in July of 1973, arsonists destroyed the building, using prayer books to ignite the flames. They targeted the building because the gay congregation worshipped there. Despite its liberal reputation, San Francisco was not immune to the currents of homophobia that many MCC congregations encountered at the time. The attack on MCC San Francisco was the fourth arson attack on an MCC congregation that year. Longtime MCC-SF member Lynn Jordan told me the lesson he took from the arson attack: “You destroyed a church building. You did not destroy the church.” But the fire spurred the church’s commitment to buy a building of its own—and to start raising money for it. According to MCC founder Rev. Troy Perry, Dianne Feinstein, who was then a city supervisor, made the first post-fire donation to MCC-SF’s building fund.

The congregation found 150 Eureka Street in 1979. Larry Hughes, MCC-SF’s treasurer, remembered looking at spaces all over the city. But they wanted to be in the burgeoning queer-friendly Castro—and Voice of Pentecost, the church that sold MCC-SF the building, wanted out. By the late 1970s, the Castro was an iconic gayborhood in sociologist Amin Ghaziani’s sense of the term: a place where gays, lesbians, and other queer folks lived their full lives, opening businesses, starting community organizations, shaping the culture, and building political power. The Castro had the tangible feel of a gay counter-public, freeing for those who reveled in its unapologetic outness, constricting for those who chafed at its racism, sexism, and classism in a gay male key, and reeking of sin for others still. A newspaper account of the sale noted theological differences between the two churches who were exchanging the building: Voice of Pentecost, like other conservative churches in the city, “has called San Francisco a modern Sodom and Gomorrah.”

The place, by most accounts, was a dump. Board member, Bob Lawrence, remembered the ever-present structural problems: “We were meeting in what became the library, and all of a sudden we heard this noise. Out in the middle of the floor, up popped this raccoon. We all screamed and went running.” Congregant Dennis Edelman remembered the questionable aesthetics: “The carpet was this vomit green shag carpet, all over the whole sanctuary. It had these creaky, old, pews that didn’t hang together. If you sat wrong in them, you’d get caught in a crack, and it would hurt.” But it was a home, and a space they could share with the community.

The church soon welcomed the broader community into its doors. According to a newspaper article, “The MCC Board of Directors is prepared to offer meeting space, free of charge, to social, political and other religious groups.” The space wasn’t always free, but in 1979 the church leaders could not have known how life-saving it would become. Over the next twenty-five years, as AIDS emerged, thousands got sick and died and LGBTQ movements grew and changed, 150 Eureka Street became a laboratory of personal, social, political, and spiritual resistance.

***

Queer spaces create queer possibilities. And by sharing its space promiscuously, MCC-SF helped queer possibilities proliferate. They allowed countless groups and gatherings to experiment with creative acts of resistance, large and small. And they let themselves be changed by all that was happening in the building, experimenting with their own acts of resistance. Here is a non-exhaustive, entirely evocative list.

Welcome the Outcast

MCC-SF folks knew what it was like to be outcast. Many members were cast out of the churches they grew up in because they were queer. Some had been cast out of families. And some felt cast out of the gay community because of their religious commitments. At 150 Eureka Street, they made space for people who were likewise cast out.

One of the most ambitious of such projects was resettling dozens of gay Cuban refugees during the Mariel Boatlift. In 1980 thousands were thrown out of Cuba by the country’s leader, Fidel Castro, in a mass expulsion. Small boats took Cubans to Florida in search of a new home. These refugees, known as Marielitos, included a large number of gay men and lesbians, many of whom had been imprisoned before being expelled. Queer Marielitos faced a particular bind: U.S. immigration law forbade both the entrance of known homosexuals into the country and the return of migrants to communist countries. Many lacked family networks that could provide sponsorship as they applied for U.S. citizenship. When MCC learned of the presence of gay and lesbian refugees in migration camps, the denomination organized its churches and members to become sponsors and help queer Marielitos live in the United States.

150 Eureka Street became the site of that effort in San Francisco. The church coordinated with a wide range of gay and lesbian groups to recruit sponsors, donate clothing and household items, offer English classes, and help find jobs. The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, an order of queer, campy nuns, made their first major public performance at 150 Eureka Street in a fundraiser for gay Cuban refugees. When they landed in San Francisco, gay Cubans were taken by charter bus directly to MCC-SF. “Once inside the MCC building,” a newspaper article wrote, “the refugees took the first steps in their Gay Americanization. One room was filled with clothes from which they took what they wanted. A buffet had been prepared. One by one their names were called and they were introduced to their sponsors. These were emotion-charged moments as total strangers entered into arrangements they would never have imagined three months ago.” The Cuban refugee resettlement program was a prelude of sorts to the AIDS crisis: an early effort at coordinating gay and lesbian organizations in the city to address a significant social need.

Innovate Queer Rituals

One building-specific ritual MCC-SF performed in their earliest years on Eureka Street was re-baptism. Baptism is a sacrament of religious identity and spiritual consecration that involves water, sprinkled on a person’s forehead or encompassing the entire body (known as full-immersion), to represent a new birth as a Christian. When it departed Eureka Street, Voice of Pentecost left a baptismal font the size of a large tub at the front of the sanctuary. Not all MCC-SF members came from Christian traditions that performed full-immersion baptism, and many had been baptized earlier in life. But a significant number of MCC-SF members believed their earlier baptisms were incomplete because they were conducted before coming out. After finding a spiritual home that accepted them, people started asking MCC-SF to re-baptize them as out gay/lesbian people. Rev. Jane Spahr was an associate minister in the early 1980s and recalled the church packed with people coming forward to be re-baptized. “That was weepy for me,’ she told me. “It was, like, this is so right. It is a sacred thing to be who we are.”

As the AIDS epidemic hit San Francisco, another queer ritual the church developed was a standard church rite forged anew in the heat of AIDS. Rituals remembering those who died from AIDS were fraught. Finding a funeral home that would host an AIDS funeral was one challenge. The disease was novel, lethal, and its routes of transmission were unclear. Many service providers, from ambulance drivers to funeral directors, refused to interact with people with AIDS in life or with their bodies in death. Another set of challenges were social and emotional, including complex dynamics of the closet, homophobia, and the social stigma of AIDS. Many funerals were held in churches where the person’s cause of death was never spoken and their closest beloveds and caregivers never acknowledged.

150 Eureka Street became the site of hundreds of AIDS funerals in the years before effective treatment for HIV existed. It was known as a place where lovers, partners, and friends were all recognized as mourners, and the stories of those who died could be more fully told. People facing their deaths were able to design rituals that reflected their beliefs and the church innovated a format that eschewed a single eulogy and invited multiple loved ones to share stories of the dead. One of the early AIDS funerals at 150 Eureka Street was a 1982 service for Patrick Cowley, an EDM composer known for his work on gay porn soundtracks. Disco diva Sylvester, Cowley’s artistic partner, sang at the “real revivalist funeral” that would have been hard to pull off anywhere else. As AIDS unfolded, people in San Francisco and beyond got to know 150 Eureka Street because they attended so many funerals there.

Share Information and Grapple with Difficult Things

When you’re in a crisis like AIDS, when not much is known, people are terrified, and information needs to be shared with a community suspicious of medical and political authorities, a church building can be a trusted space. 150 Eureka Street was a vital site for community meetings, town halls, and other gatherings that allowed those most vulnerable to learn more about AIDS. The building became a resource used by AIDS organizations to stay in conversation with the community.

AIDS was first discussed publicly in the summer of 1981. In 1982, a small group of gay activists and medical doctors in San Francisco founded the KS Foundation—named for Kaposi’s Sarcoma, one of the most prevalent early opportunistic infections whose telltale purple lesions became symbolic of AIDS. By July of that year, they were sponsoring regular community forums about the new disease at 150 Eureka Street. Project Inform, an organization that pioneered community-based research into effective treatment, started holding its AIDS Town Hall meetings there in the mid-80s, discussing the range of treatments, conventional and alternative, people were using, what their effects were, and how people could get them. 150 Eureka Street also housed the Documentation of AIDS Issues and Research (DAIR) library. In the years before the internet, when medical journals and studies were more difficult for the public to access, DAIR gathered every existing scientific publication about AIDS and made them available for anyone to read and photocopy.

Medical mysteries and existential crises require not just receiving information but grappling with hard things. MCC-SF gave folks a place to do so. One difficult question they faced was how sex would need to change in the face of AIDS—not a topic many churches would entertain. Early in the epidemic, 150 Eureka Street hosted events focused on safe sex and how to make it hot. When it became clear that substance use was a risk factor in HIV transmission, MCC-SF hosted dozens of recovery groups where sexuality and AIDS could be openly discussed. At one point, 12-step groups became the most common way people joined the MCC-SF congregation.

Facing AIDS also meant facing difficult personal questions about sickness, loss, and death. MCC-SF sponsored groups for people who were HIV+, people who were HIV-, people facing other life-threatening illnesses, and for caregivers. And it allowed for painful, controversial conversations about end of life. In 1991 Rev. Jim Mitulski gave a sermon about Final Exit, a book advocating assisted suicide, and in 1993 the president of the Hemlock Society spoke at the church. MCC-SF did not itself advocate for assisted suicide, and its members were undoubtedly divided on the issue, but they wanted folks to talk about a dilemma that so many were encountering. They made the space for them to do so.

Make Change

MCC-SF rented space to all kinds of change-makers, from the more respectable (including, at one point, all three gay Democratic clubs in the city) to the more insurgent (like AIDS Action Pledge, which became ACT UP San Francisco). The building buzzed with plans for protests, campaigns, vigils, mailings, and other tangible work for social change.

As AIDS progressed, losses piled up, and the hope for treatment seemed to stall, MCC-SF started seeing itself as a potential agent of change, not just a host for others’ efforts. The shift toward greater engagement as a congregation started in the mid-90s after Rev. Jim Mitulski returned from a sabbatical. He spent a semester at Harvard where he enrolled in a course on AIDS and was able to learn more about the crisis he had been facing daily for years. The class helped him see the political dimensions of AIDS more clearly, and it increased his resolve to commit the church to more direct action.

An opportunity to put that into practice emerged in 1996 when Rev. Mitulski was approached with an invitation to play a small part in a bigger story about the legalization of medical marijuana. Medical marijuana was an important issue for people living with AIDS; pot relieved pain and it stimulated appetite. AIDS activists joined cannabis reformers to work toward legalizing medical marijuana. They made progress with the city, opening the Cannabis Buyer’s Club in 1991. But they met with resistance from the state, resistance that reached a boiling point in 1996 when the California State Bureau of Drug Enforcement, under the guidance of a conservative Republican attorney general, raided the Club and shut it down.

This posed a political problem for San Francisco’s pro-pot politicians, activists, and citizens. And it posed a medical problem for people with AIDS and other diseases who depended on marijuana to ease their suffering. They sought a way to continue the distribution of medical marijuana in a way that was legal—or at least protected—in a place that people would trust enough to go and that state authorities would be reluctant to disrupt.

According to Rev. Mitulski, city officials reached out to him to ask if he would consider medical marijuana distribution at the church. The project would be a collaboration with Healing Alternatives, the San Francisco Buyer’s Club that already distributed a wide range of unauthorized but promising AIDS treatments on Tuesday nights at MCC-SF. Healing Alternatives would acquire the marijuana and distribute it at MCC-SF under the guidance of Rev. Mitulski. He said yes—and he organized other congregations to become distribution sites as well. “I believe the moral stance is to break the law to make this marijuana available,” Mitulski said in a newspaper interview. “Our church’s spiritual vitality has always come from a willingness to act where people have been reluctant to act. This is not a bystander church.”

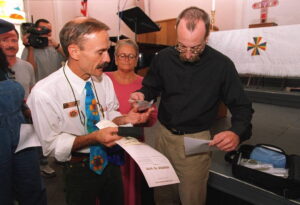

(Image source: Lea Suzuki/SF Chronicle. Rev. Jim Mitulski hands out a bag of marijuana.)

This is an example of the church using the building itself as a physical and symbolic resource for direct social action. The church building gave moral cover to a project about which many still had reservations. And distributing marijuana in the same room in which the church held its worship services highlighted the sacred intention in the act. It set a scene that was unmistakable. “In a ceremony that was reminiscent of holy communion,” wrote one account, “the minister in the church sanctuary handed each recipient who shuffled by a small plastic baggie. Instead of a communion wafer, the baggies contained two small packages of marijuana, about enough to make seven or eight cigarettes.” This event marked the beginning of a period where the church looked at its building and asked itself, yet again, how it might be used to make change. Except this time the congregation itself was the change-maker.

***

150 Eureka Street was not the only community-run space in San Francisco where these kinds of conversations, actions, and efforts happened. The Women’s Building was another. And people and groups rented other spaces for their events and programs, spaces that were larger, quieter, less run-down, and not affiliated with religion. But as one of the first LGBTQ-owned buildings in the city, it offered possibilities that other spaces could not. Other churches refused to be sites of queer Holy Unions and AIDS memorials that recognized lovers and friends as mourners. Other organizations were reticent to invite sex workers, gay dads, dykes who liked high tea, or debates about oral sex to use their space. And groups that were supportive of the kinds of conversations that happened at 150 Eureka Street almost always had landlords to consider, in a city where real estate was expensive and lacking an office could put a group’s work into jeopardy. For years the queer community in San Francisco tried to organize an LGBTQ Community Center, which finally opened in 2002. But from 1979 through the worst of the AIDS epidemic, 150 Eureka Street served that function, because it was owned and operated by a queer church and it became a space that other queer people trusted.

2025, all these years later, is a strange moment to be writing about resistance and buildings. Or a hard one. Real estate markets, gentrification, and the underlying problem of economic inequality, have made purchasing real estate a laughable prospect for most people and most groups, especially those with resistance on their minds. 150 Eureka Street itself has been overcome by such forces. Many congregations endowed with buildings find themselves without the people or the funds to maintain them. Some have gone through the painful process of re-thinking their building, its uses, and how it might better serve the congregation’s values and the community’s needs. And the protections of church, of sanctuary, are under continual assault by an administration intent on leaving no place sacred in its lawless pursuit of Black and brown immigrants.

I don’t tell this story to evoke a romantic past, unattainable in the present. I tell it as a reminder of the importance of space—physical and spiritual—and the value of protecting it, in order for resistance to thrive.

Lynne Gerber is an independent scholar and audio producer in San Francisco. She is the Co-Creator and Executive Producer of When We All Get to Heaven, a documentary podcast about a queer church, the Metropolitan Community Church of San Francisco, and how it got through AIDS in the years before treatment.