The Catholic Worker's Radical Vision

Keeping a century-old movement alive, and renewed for today's problems, in the fight for social justice

(Image source: Gregory A. Shemitz/National Catholic Reporter)

On a Wednesday morning in early September, the four-story townhouse at 55 East 3rd Street, in New York’s East Village neighborhood, hums with activity. In the downstairs kitchen, past a dining area bedecked with portraits of the late Pope Francis and French nun Thérèse of Lisieux, a half-dozen volunteers are preparing lunch. Up the stairs, a man affixes stickers to stacks of newspapers, labeling them with the addresses of their recipients; they line an entire wall of the cavernous auditorium where he works. A few women sit quietly near him or wait their turn to eat on the stairs below. Some live in the house, and others have arrived seeking the midday meal, which is served here five days a week to anyone who needs it.

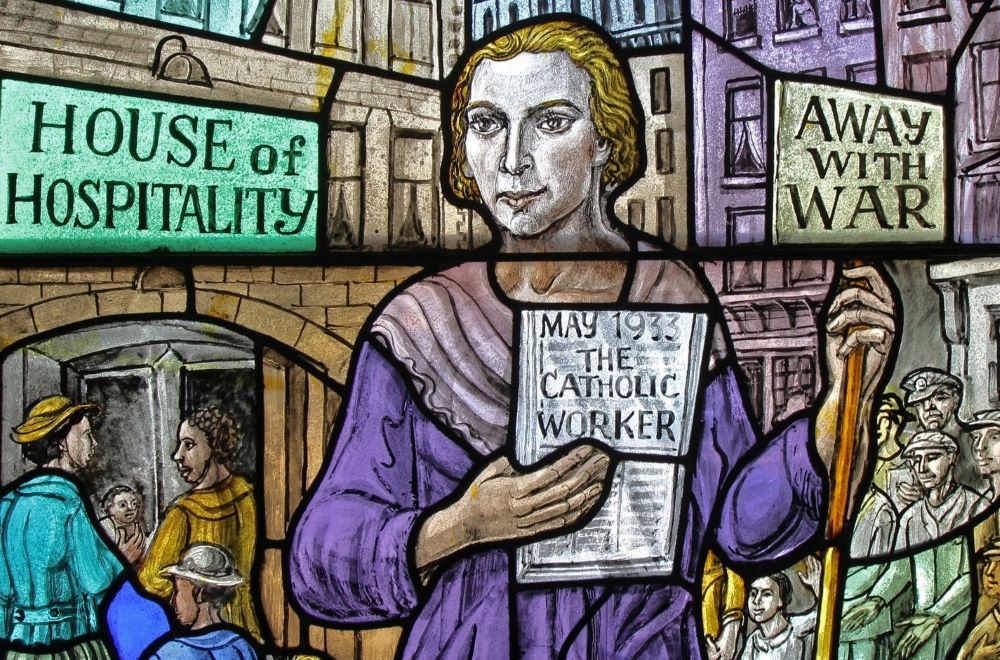

This is the Maryhouse—not a charity, but a “house of hospitality,” explains Martha Hennessy, who has spent time at the house on and off since it first opened in 1975. Hennessy’s grandmother was Dorothy Day, a journalist and activist who, along with French theologian Peter Maurin, started a newspaper called The Catholic Worker in 1933. That paper is still published out of the Maryhouse on East 3rd Street, but the Catholic Worker is something much bigger: a community aid network and radical Christian movement that promotes values like social justice, pacifism, and mutual aid. Hennessy has been arrested multiple times for her protests against nuclear weapons, but she now channels most of her energy toward helping around the house.

“I grew up being told, ‘pay attention to the suffering of the poor, and try to practice loving kindness,’” Hennessy told me, sitting down in an office on the second floor of the Maryhouse. “I got that through my mother and my grandmother. It’s a very clear message—very important in the 20th century, and now in the 21st century.”

In the U.S. and around the world, religious observation, including membership in the Catholic Church, is on the decline. At the same time, people—particularly members of the younger generation—are seeing a greater need to confront intertwined issues like poverty, militarism, and climate change. Some are finding answers in the Catholic Worker, drawn in by its founders’ calls to live communally, protest injustice, and return to the roots of Catholic teaching. Today, The Catholic Worker newspaper is still mailed out to about 20,000 subscribers, and Catholic Workers operate hundreds of houses of hospitality around the globe.

Intentionally decentralized and diffuse, the Catholic Worker means different things to different people, with some compelled by Day and Maurin’s religious lessons and others by their social justice activism. Regardless of their reasons, Catholic Workers are helping to keep the nearly century-old movement’s message alive. In doing so, they offer an example to others trying to live outside capitalist consumerism, protest war and the genocide in Palestine, or find community in an increasingly secular and atomized world.

***

Though Dorothy Day always credited Peter Maurin with founding the Catholic Worker movement, its earliest expression—a newspaper of the same name—could not have appeared without her. Day was a journalist who spent her early twenties working for socialist publications; later, after converting to Catholicism at the age of 30, she wrote for Commonweal, a liberal Catholic magazine that exists today. Covering growing poverty and social unrest during the Great Depression, she began to feel that leftist organizing lacked a Catholic voice. When Maurin, a French activist inspired by Saint Francis of Assisi, showed up at her door in 1932 after reading some of her articles for Commonweal, Day found an ideological partner who channeled her knowledge of journalism and American culture into a concrete form.

The two published the first edition of The Catholic Worker newspaper on May Day in 1933, handing it out to workers celebrating in New York’s Union Square. But Maurin had a grander vision, which went beyond educating people suffering from poverty and homelessness and actually offered them material aid such as food and a place to stay. He and Day opened their first “house of hospitality” in New York City later that year, which doubled as an office for the newspaper.

(Image source: Our Sunday Visitor)

“It’s really this bare-bones sort of operation at the beginning, where they’re getting money from different sources in order to keep up the house as well as shelter folks,” said Jacques Linder, a religious studies instructor at the College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts who has researched the Catholic Worker. “What happens is that people just keep coming and being inspired by Dorothy and Peter’s vision. It grows and expands to this wider movement.”

People around the country learned about the pair’s ideas through The Catholic Worker newspaper, and houses of hospitality soon opened in cities like St. Louis and Detroit. Volunteers were encouraged to live in the houses alongside the people they were helping in a condition of voluntary poverty; in turn, many of the people who received aid went on to become Catholic Workers themselves.

From the beginning, Linder said, the movement promoted two goals: living the Gospels by engaging in “works of mercy,” such as feeding and clothing the poor, and advocating for social justice to address the structural problems that create poverty and inequality at the root. Day was greatly inspired by Catholic concepts like the Mystical Body of Christ, which teaches that all Church members are united and animated by the Holy Spirit, and the Sermon on the Mount, a collection of Jesus’ instructions for living a moral life, such as loving one’s enemy and practicing forgiveness.

At the same time, her background as an activist for women’s suffrage and workers’ rights, along with her pacifism, undergirded the Catholic Worker’s agitation against war and militarism; the paper refused to take a side during World War II, and Day was one of the first to criticize the United States’ decision to drop bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. She urged nonviolent opposition to war, such as the burning of draft cards, and was jailed four times between 1955 and 1960 for refusing to participate in civil defense air raid drills during the Cold War. These positions led to a loss of support for her work, even from within the movement’s own ranks.

The spirit of the Catholic Worker has also always been anarchist, though Maurin didn’t identify as such during his lifetime, preferring the term “personalist.” Day, however, said later in her life that she had been an anarchist since some of her earliest actions protesting for women’s suffrage outside the White House. What this meant in practice was a rejection of the role of the state or other formal institutions in providing “charity” to people in need, instead urging people to care for each other directly—what today is commonly known as “mutual aid.”

But rather than just protesting the world as it was, Day and Maurin wanted to share a vision for what it could be: a more fair and just economic system known as “distributism,” a theory developed in the late 19th century that provided a grassroots, cooperative alternative to both laissez-faire capitalism and state socialism. For Maurin, this was not an attempt to bring a foreign concept into Catholicism, but rather a return to the very earliest Catholic teachings, which he believed had been long neglected by the Church. In his writings to Day, which later appeared in the pages of the Catholic Worker as part of a series called the “Easy Essays,” Maurin said that his goal was “to create a new society within the shell of the old, with the philosophy of the new, which is not a new philosophy, but a very old philosophy, a philosophy so old that it looks like new.”

The Church’s response to this pressure varied, Linder said; while some bishops denounced the Catholic Worker’s leftist orientation, particularly during the McCarthy era of anti-communism, others supported its commitment to helping the poor. In 2000, the Vatican formally recognized Day as a “Servant of God,” the first step toward achieving sainthood, despite her well-documented opposition to canonization within her lifetime.

For Brian Terrell, a longtime Catholic Worker who spent several years working with Day after joining the movement in the late 1970s, her most important lesson was that “ideas and beliefs matter.” The Catholic Worker followed Church teachings, he believes, but also stood apart from the Church.

“You could have these wonderful things in the Gospels—the idea of loving your enemy, sharing what you have with the poor—but they don’t affect how you live your life.” Terrell said. Day and Maurin, on the other hand, “were actually putting that into practice.”

***

Dorothy Day died in 1980, in an upstairs bedroom of the house at 55 East 3rd Street, where she spent the last five years of her life. Her death led to concerns, both inside and outside of the movement, about what would happen to the Catholic Worker without her influence. But it has continued to flourish because of its decentralized structure.

From its earliest beginnings, Maurin saw the Catholic Worker as an “organism,” not an organization. Day resisted calls to incorporate the paper or any of the houses as nonprofits, even in the face of threats from the Internal Revenue Service. Although some houses of hospitality have since taken steps to achieve tax-exempt status, the movement as a whole has remained informal; anyone can establish a Catholic Worker house, and no one authority determines who is and isn’t part of the movement. Even now Hennessy isn’t sure exactly how many houses exist around the U.S. today, with estimates ranging between 150 to 200; dozens more operate around the world, in countries like the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, South Korea, Uganda, Mexico, and Sweden.

Over the years, many of these communities have remained engaged in social justice and anti-war activism, protesting nuclear weapons, U.S. invasions in Latin America and the Middle East, and drone strikes in Yemen and Afghanistan. After the Israeli assault on Gaza began in October 2023, Catholic Workers joined protests in support of Palestinian liberation and against arms sales to Israel. And since the start of President Donald Trump’s second term, others have shown up outside Immigration and Customs Enforcement field offices to escort immigrants to their appointments and to block deportations. Still others have been drawn to promoting climate justice; over the course of six months in 2016 and 2017, two Catholic Workers even engaged in a “campaign of arson” against the Dakota Access pipeline, protesting its effects on the environment, climate change, and Indigenous sovereignty. The FBI labeled them “domestic terrorists,” and the pair received lengthy prison sentences.

The Catholic Worker’s commitment to activism has led to differences of opinion almost from the beginning. As far back as 1957, Day wrote of some readers’ complaints that “the paper is not what it used to be. Too much stuff about war and preparation for war, and the duty of building up resistance.” That rift has persisted over the decades, Terrell said. Some houses want to “present the Catholic Worker as, ‘We feed poor people. We distribute used clothes, we find housing, and we pray’… They don’t want to be seen as the people protesting the ICE raids. They want to be seen as the nice, good people.”

Some Catholic Workers and scholars of the movement have in recent years emphasized Day’s Catholicism as her primary motivating force, arguing that the current-day movement’s adoption of liberal causes, like support for the rights of queer and transgender people, stray from her original vision. Others, such as Terrell, have made the case that she would have wanted Catholics to question Church teachings that don’t align with their moral values; indeed, Day called for Catholics to live in a state of “permanent dissatisfaction” with the Church, promoting the idea that lay members should have just as much say in the direction of the faith as the clergy.

It’s also in many ways an aging movement, with many Catholic Workers who joined in the 1980s and 1990s beginning to move out as they grow older; houses of hospitality have had difficulties drawing in and retaining younger members, Hennessy said. College debt weighs down many volunteers in their twenties and thirties who may not be able to live in voluntary poverty the way that Day and Maurin first envisioned. The atomization and distraction brought on by social media and the internet, Hennessy believes, also disrupt some of the communal interactions within houses, which have struggled with whether to allow cell phones during dinner, for example.

“Living in community is extremely demanding,” Hennessy said. “It does take a certain amount of skill and experience to know how to live with each other.”

At the same time, the movement continues to hold appeal for young people growing increasingly aware of intertwined crises like homelessness, income inequality, and environmental destruction. Many are disillusioned with the idea that they should go to college and work for nonprofits if they want to make a difference in the world. In 2010, then-twenty-year-old Theo Kayser moved to Los Angeles to volunteer in a soup kitchen on Skid Row; he ended up spending seven years at the city’s Catholic Worker house, and last year opened a new house of hospitality in his home city of St. Louis, along with a few other young Catholic Workers.

Kayser came to the Catholic Worker from a radical anarchist, rather than religious, perspective—what he described as a sense of “alienation under capitalism.” Recounting his origin story years later, he said he felt “that there was more to life than just getting a job and working for the weekend and your two weeks’ vacation every year. Like maybe we could try to live for more than that, and try to work towards higher ideals.”

Younger Catholic Workers like Kayser are also helping usher the movement into a digital age, starting Facebook groups and Instagram pages for houses in different cities. Some are grappling with areas in which the Catholic Worker has traditionally been lacking, such as addressing anti-Black racism. Kayser and Lydia Wong, a Catholic Worker based in Chicago, run a podcast called Coffee with Catholic Workers, where they interview guests about topics as diverse as queerness within the movement, climate activism, and what it’s like to live off-grid. On his personal Instagram, Kayser shares quotes from Dorothy Day and updates from protests around the country.

Terrell believes this is possible because Day and Maurin’s ideas speak to “something very human, not just for Catholics.” As a decentralized movement, the Catholic Worker has also stayed flexible, with some of its members honing in more acutely on the problems of 21st-century late-stage capitalism. In recent years, Gen Z and Millennial Catholic Workers have opened houses in cities like Portland, Oregon, with a vision of creating alternative forms of economic and social life, hewing closer to what they see as Day and Maurin’s original vision. Rather than engaging in mass protest or international organizing, some of these houses are focusing on hyperlocal change through “community-scale” economies. This can look like urban homesteading, or growing food on small plots in the middle of a city, and mutual aid networks, such as distributing food and clothing to one’s neighbors and friends without the backing of donations or sponsorships.

For others in the movement—particularly those who knew Day, such as Hennessy and Terrell—its political program is inseparable from the Catholic Worker’s other goals. Terrell lives on a farm in Iowa, where he and his wife Betsy share space with a rotating cast of Catholic Workers and other guests. They milk goats, weave fabrics, and practice the kind of farming lifestyle, largely disconnected from modern systems of capitalist consumption, that Maurin championed. But Terrell also travels semi-annually to protest at a nuclear test site in Nevada and has made solidarity trips to Afghanistan, Iraq, and Palestine; in May, he was one of six arrested at a National Nuclear Security Administration campus in Kansas City, Missouri.

He quoted Albert Camus, who told a crowd of monks in 1948 that “Christians should speak out, loud and clear” and “confront the blood-stained face history has taken on today.” Protest, he believes, is part of what it means to be a Catholic Worker, even if it looks different for every member of the diffuse movement.

“Dorothy said too that we can’t judge each other based on what form it’s going to take for each person and what kind of risks people are going to take,” Terrell said. “But still, silence is not an option.”

Diana Kruzman is a freelance journalist covering religion, climate change, and human rights, in the U.S. and around the world. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, The Intercept, the Christian Science Monitor, and other publications. She lives in New York City.