Can Anyone Be Against Us? Resisting Disappearance Across the Américas

The religious leaders and communities working to protect people that governments want to deport and disappear

(illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios. Photos: Veronica G Cardenas & Claudio Cruz/AFP via Getty Images, Shannon Stapleton-Pool/Getty Images)

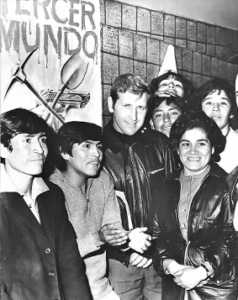

When he was a young boy—eleven or twelve, maybe—my dad, Daniel, met clergy from the Movimiento de Sacerdotes Para el Tercer Mundo, or the Movement of Priests for the Third World. His uncle Oscar, a professional boxer and friend of Argentine President Juan Domingo Perón, was close with the group, often referred to by the press as “slum priests.” Having been turned away from serving as an altar boy because of his rowdy and often defiant behavior, my dad was immediately drawn to these religious outsiders, who he soon learned had also been rejected by church leaders. He begged his uncle to take him to the street corners where they preached their message.

The movement emerged in Argentina in 1967 following a meeting of eighteen clergy representing Latin America, Asia, and Africa in response to Pope Paul IV’s “Populorum Progressio,” an encyclical on global “underdevelopment.” According to Domingo Bresci, a member and historian of the movement, after journalists referred to the group as the “Priests of the Third World,” clergy began to name themselves “Priests for the Third World,” committing themselves to the struggle against capitalism and neocolonialism. For them, the Third World was not only a geopolitical location but also an ideological one that exceeded borders. By Third World, they were also referring to poor and oppressed communities inside the First World, articulating a transnational politics of solidarity.

Last December, my family returned to Argentina for the first time since we fled the country in 1998. The trip was part homecoming, part fieldwork. I was there to reconnect with family and revisit places from my youth, but also to conduct research for my next book—Siempre Estoy Llegando—a collaboration with my dad, who is now a Christian pastor ministering to a largely migrant congregation in Winston Salem, North Carolina.

The day after landing in Buenos Aires, I visited the Priests for the Third World archives at the Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada (ESMA) Museum and Site of Memory, a former clandestine detention, torture, and extermination center during the military dictatorship of 1976 to 1983. I came across accounts of priests, including Bresci, who organized marches and strikes alongside students and workers in the years before and during the dictatorship. Movement clergy were brutally repressed; many were taken hostage by the police and labeled “subversives,” a category applied to anyone who posed a threat to the right-wing regimes. Even still, as Bresci makes clear in his chronicle of the movement, the clergy “reiterated their conviction to always remain alongside the people in their freedom struggles, in accordance with what they considered the unavoidable demands of the gospel.”

(Image of Carlos Múgica from Archives of Memory, Buenos Aires, Argentina.)

Before the military regime took power, then-president Isabel Perón’s administration established the Triple A (Argentine Anticommunist Alliance), paramilitary death squads that disappeared and murdered artists, union leaders, and slum priests like Carlos Múgica, one of the most well-known members of the movimiento. My dad remembers hearing the news of Múgica’s assassination and cites that moment as a turning point in his childhood, when he realized that no one was safe from state violence. Two years later, the military overthrew Perón and launched a “Process of National Reorganization,” kidnapping, torturing, and disappearing 30,000 people they deemed “subversive.” My dad’s teenage years were shaped by the presence of tanks and other armored vehicles parading along the streets of Buenos Aires, checkpoints along busy intersections where officers were known to frisk and harass people, with intimidating officers shutting down parties and nightclubs in the middle of the night—threatening to arrest anyone who refused to comply with their orders. During our return to Buenos Aires, my dad took our family to his middle school to show us the plaque on the sidewalk honoring his classmates who were taken by the military regime—Carlos Hugo Capitman, Guillermo Hernan Cupaioli, and Martin Elias Bercovich.

(Daniel Sostaita points to his classmates’ names on a plaque honoring the disappeared. Photo courtesy of the author.)

“I survived a dictatorship in Argentina during my youth,” my dad reflects during an interview with me. “Now, in my old age, I am once again organizing for a democracy for all people.” As a pastor and organizer, he sees firsthand how the Trump administration’s designs for mass deportations are not only terrorizing his community but also repeating hemispheric legacies of death and disappearance. As he’s told me many times, he has seen this before—as have all those who survived Operation Condor, a U.S.-backed campaign of political repression that disappeared “subversives” (largely union and student activists) across Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Brazil from the late 1970s until the early 1980s.

My dad isn’t the only one referring to the abduction and detention of migrants in the U.S. as a practice of state-sponsored disappearance. Magazines like The Nation reported on Mahmoud Khalil’s kidnapping as a political disappearance, describing how “[agents] abducted Khalil, took him to an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention center in New York City, then moved him to a different, undisclosed facility.” His wife, Noor Abdalla, testified that her husband was shackled and snatched in the middle of the night and that it took days to locate him afterwards. Only weeks after Khalil was disappeared, Tufts University student Rümeysa Öztürk was abducted by masked and plainclothes ICE agents in broad daylight. Surveillance footage shows that merely a minute after agents swarmed her, Öztürk was disappeared into an unmarked SUV. Within the span of twenty-four hours, ICE moved her to three separate locations in three different states, making it impossible for Öztürk’s legal team to locate her. Speaking to the U.S. Congress, Robyn Barnard, the director of Human Rights First, describes the Trump administration’s deportations of people to places that are not their countries of origin, including Nayib Bukele’s “mega-prisons” in El Salvador, as a practice of “disappearance.” And in early 2025, organizers launched a “United States Disappearance Tracker” to document the people impacted by the Trump administration’s mass deportation campaign.

Reflecting on the act of disappearing people, performance studies scholar Michelle Castañeda, in her book Disappearing Rooms: The Hidden Theaters of Immigration Law, proposes that the term “disappearance” points to deportation’s theatricality and draws connections between state violence across the Americas—“unmarked vans kidnapping people in the middle of the night, people being held captive at unknown locations, fear of inquiring about a relative’s whereabouts lest one come to the attention of the authorities, and the official obfuscation of deaths in detention centers and on the U.S.-Mexico border.” She argues that using this term is not meant to “elide historical differences but to underscore what is shared: namely, a type of theatricality in which the state compounds the loss of life with the loss of reality.”

To be clear, the surveillance and criminalization of immigrants precede the Trump administration and implicates Democratic and Republican administrations alike. My dad founded his congregation—Iglesia Cristiana Sin Fronteras—in 2006, in the years following the creation of ICE and the passage of the Patriot Act, which granted the federal government unprecedented powers over immigration enforcement. That year also saw the historic Primavera de Migrantes or “Spring of Immigrants,” a season of mass demonstrations and strikes led by undocumented people in response to H.R. 4437, which would have made unlawful presence a crime (as opposed to a civil offense) and broadened the definition of “alien smuggling” to charge anyone providing aid to undocumented people, including churches, employers, and family members. Political scientist Cristina Beltrán describes the 2006 protests as marking a “space of appearance” for undocumented immigrants, communities that U.S. politicians and the media had previously imagined as silent and invisible. She writes of these mobilizations as a refusal to be disappeared. Since then, members of my dad’s church have sheltered each other from bipartisan attacks, providing “know your rights” trainings and mutual aid, legal support and other forms of care to survive crises like workplace raids during the Bush administration, the drastic rise in deportations under Obama, and the threats of mass deportations under Trump.

Initially, Iglesia Cristiana Sin Fronteras met in an elementary school gymnasium. Our family was undocumented and my dad struggled to find a denomination or religious organization willing to support his church financially. “People thought of me as a heretic, a nutcase … Either nobody trusted me, or they underestimated me.” He was shunned not only because of his legal status (or lack thereof), but also for his vision of a church that organizes against all forms of oppression.

Today, Sin Fronteras has established itself as one of the largest and most active Latinx congregations in the state. In recent years, they have played a crucial role in the struggle to defend migrants from detention and disappearance in Forsyth County and North Carolina more broadly—providing direct aid to families undergoing deportation proceedings, hosting workshops for migrants to know their rights and to obtain alternative IDs that grant everyone access to pharmacies and bank accounts, and organizing politically for increased protections and resources for vulnerable communities. For example, in 2019, they joined an interfaith and multiracial team in supporting the Forsyth County Sheriff Bobby Kimbrough’s commitment to refuse ICE detainer requests, meaning he would not hold migrants in criminal custody on behalf of ICE or notify the agency before releasing them from custody. The campaign was only successful because of its commitment to coalitional politics, that is, to organizing across difference. According to my dad, organizers drew connections between the struggle against ICE detainers and the criminalization of youth of color—making it clear that it was “all of us or none.” In spite of these grassroots efforts (or perhaps, because of them), the North Carolina legislature overrode the governors’ vetoes and passed H.B. 10 in 2024 and H.B. 318 in 2025, requiring local law enforcement to comply with federal immigration officials. Even still, the church continues to strategize ways to defend and shelter each other. In some cases, they have continued to offer material aid and spiritual counsel in the wake of deportation, refusing to abandon church members displaced by the state, refusing to accept disappearance.

In a lenten devotional for the Cooperative Baptist Foundation earlier this year, my dad reflected on the impact of H.B. 10. “For immigrants,” he writes, “this law only adds to a climate of fear and uncertainty. Such policies often reinforce harmful stereotypes, painting immigrants as threats rather than recognizing their humanity and worth.” His devotional goes on to reference Romans 8:31-32, asking readers, “If God is on our side, can anyone be against us? God did not keep back God’s own Son, but God gave him for us. If God did this, won’t God freely give us everything else?” During a time when migrants are under attack—not merely in the U.S. but globally—I am compelled by my dad’s words. Not only because this passage from the Book of Romans situates God as being on the side of migrants, as allying himself with the oppressed and displaced, but more so because of the passage’s ambition. God will give migrants everything; no one can stand against us.

These words may seem naive in a moment when Stephen Miller, the White House deputy chief of staff and architect of mass deportations, is promising the “most spectacular immigration crackdown” in this country’s history. But I choose to see it as a prefigurative politics, by which I mean a way of living in the present as if the future we desire is already here. Migrants who cross borders without authorization, whose mobilities transgress walls and checkpoints, whose restless urge to practice self-determination defies the First World’s most cutting-edge surveillance technology, put this kind of politics into practice every day. They subvert a global politics of deterrence—border walls and their razor wires, family separation and “zero tolerance” policies. Their movements challenge the present—the sovereignty of nation-states, the inevitability of citizenship. Like in 2006, when immigrants chanted, “¡Aquí estamos y no nos vamos! ¡Y si nos echan nos regresamos!” (“We’re here and we’re not leaving! And if you remove us, we will return!”) migrants continue to insist on their presence. They act as if God has already given them everything, as if the earth is for the meek not to inherit but to topple over.

Last year, when my family returned to Argentina, I met organizers and archivists who taught me that forced disappearance is not a practice that exists exclusively in the country’s past. As we emailed back and forth about my request to conduct research at archives located at the former Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada (ESMA) , staff warned me that over half of their team had been fired by president Javier Milei’s anarcho-libertarian administration. Since then, Milei has shut down cultural centers and human rights offices on ESMA’s grounds and threatened to defund the Memory Site Museum that houses the testimonies of survivors and that documents the center’s history of torture and extermination. For some researchers and human rights workers, Milei’s assault on these places of memory is a continuation of the dictatorship’s policy of forced disappearances.

During one morning at the archives, a researcher approached me frenziedly. “Did you hear? Las Abuelas found the 138th grandchild stolen by the dictatorship! Come with us to the press conference.” Founded in 1977, the Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo came together to find the children born to their daughters and daughters-in-law disappeared by the dictatorship and illegally adopted, often by military families. They remain active to this day, continuing to look for their missing grandchildren. I ripped off the black plastic gloves I was using to review documents and followed staff down the hall to an auditorium buzzing with excitement. Estela de Carlotto, President of the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, stood on stage surrounded by human rights workers, forensic anthropologists, and children of the disappeared who had been identified in recent years. She introduced the anonymous grandchild, a man born in 1976, the son of Marta Enriqueta Pourtalé y Juan Carlos Villamayor, students abducted from their home in Buenos Aires by plainclothes officers. Carlotto reiterated the importance of defending human rights organizations in the face of contemporary austerity measures and fascist attempts to disappear the past. She continued, promising that the Abuelas will work to find “all 300 grandchildren that are still missing.”

(Barbara and Daniel Sostaita join the Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Photo courtesy of the author.)

Carlotta’s words—like my dad’s invocation of the Book of Romans—is a prefigurative call to action, a promise that they will persist despite state attempts to defund and dismantle their work. Defending people disappeared by state regimes, whether into torture sites like ESMA or detention centers across the United States, demands a transnational solidarity and a commitment to creating the futures we yearn for in the here and now. Can anyone be against us?

Barbara Sostaita is an Assistant Professor of Latin American and Latino Studies at the University of Illinois Chicago. She is the author of Sanctuary Everywhere: The Fugitive Sacred in the Sonoran Desert.