From Good Christian Boys to White Nationalists

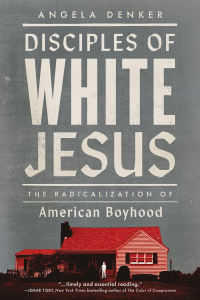

An excerpt from “Disciples of White Jesus: The Radicalization of American Boyhood”

(Image source: The Big Issue/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The following excerpt comes from Disciples of White Jesus: The Radicalization of American Boyhood by Angela Denker and published by Broadleaf Books. The book explores reasons why American adolescents are getting pulled into white nationalism and conservative Christianity.

This excerpt comes from the book’s seventh chapter, “To Fear and Love God So That?: Confirming White Boys in the Faith.”

***

First, they came for the Koreans.

I had been telling a rural, Midwestern pastor about my work and research into young, white Christian boys and men. This pastor too was a parent of boys and had spent more than a decade in a rural Midwestern church, where the pastor was beloved in town and known for speaking boldly and prophetically about divisive social issues.

As I told this rural, Midwestern pastor about my study of young, white Christian men and boys, the pastor got a far-off look in their eyes. The pastor was remembering a story.

As I told this rural, Midwestern pastor about my study of young, white Christian men and boys, the pastor got a far-off look in their eyes. The pastor was remembering a story.

It happened about fifteen years earlier, in the pastor’s previous congregation, in another small Midwestern town. The boys were now, as the pastor told the story, in their late twenties and early thirties, beginning to have children and families of their own. But they were young teens when this story took place. The pastor remembered them as good, kind boys. They were faithful church attendees and hard workers. They were respectful and engaged in the study of the Bible, particularly in this Wednesday class, known as “Confirmation,” where they spent time with the pastor learning the basics of their faith, in preparation for the rite of Confirmation, which would be celebrated in front of the entire congregation.

These were boys we’d all be proud to call our sons. They were captains of the sports teams and leaders in the school band. They helped local farmers bale hay and operate equipment, working late in the night on their families’ or neighbors’ or local friends’ fields. They opened doors for women and said “please” and “thank you.” These weren’t the boys we worried about, the ones who slunk around in the corners of doorways smoking cigarettes or surreptitiously sipping liquor, staying out late and ditching class. These were the “good boys.”

The pastor had first been a youth pastor, working with kids and teens for almost ten years before pursuing additional theological education and becoming an ordained pastor. They were one of those people who just had a knack for asking the right questions and keeping kids on task, getting them to open up and share stories and “be themselves,” in a way that teenagers often aren’t with adults, especially authority figures. So the pastor knew and loved these kids, including the aforementioned boys.

“I couldn’t believe the words that came out of their mouths,” the pastor told me, remembering, shaking their head.

The pastor was teaching a lesson about creation, a basic one really. It was supposed to be a fun exercise, a throwaway thing that serves as a kind of icebreaker, before the kids all opened their Bibles to read and learn and laugh together as they had on Wednesday after Wednesday after Wednesday for generations, in a town where the school sports coaches still ended Wednesday practices early so that kids could get to church.

“We did this exercise,” the pastor said. “I asked them: ‘If you were God, what would you include that God didn’t? What kind of world would you create?’”

The pastor walked over to a group of girls discussing the question. They brought up ideas like breathing underwater. A world without diseases.

The pastor walked across the room to the boys’ table. They were snickering, blushing. “What if we had invisibility so we could look in the girls’ locker room?”

The pastor attempted to move the conversation along, to open the Bibles and get to the “real” lesson. But the boys were getting into it now. They started talking about North Korea and the dictatorship there and its ruler, Kim Jong-Un, who had recently succeeded his father.

One of the boys just said it: “If I was God, there would be no Koreans.”

Another one nodded accordingly: “No Russians, obviously, either.”

“Definitely not any Mexicans. No Hispanics.”

The mood in the room shifted. It got personal. Their desire to eliminate North Koreans and Russians was abstract and political, but their reasoning for eliminating Mexicans or Hispanics came from much closer to home—simply because of a few kids at school they didn’t get along with.

“No African Americans either,” someone said.

There was internal debate.

“No, no, no,” another boy said. “Take that back. [The African Americans] can be the ones who clean and cook the food.”

The boys—all of them white—continued planning their white utopia, assuming that White Jesus would agree.

“I just let them keep going,” the pastor said, looking stricken. “I was internally just like: ‘Holy shit.’”

At some point the group had also banned all Jewish people, though the pastor was doubtful any of them had ever met a Jewish person. There were no synagogues or Jewish temples for at least sixty miles.

Eventually, they got to the coda of their new creation: the shining White City on a Hill.

“Women can be there, but they all have to be naked!”

They sat there grinning, proud. They’d made a plan. Now, the pastor would tell them to open their Bibles and class would go on, right?

The pastor stopped them.

“I was just really animated, really over-the-top,” the pastor recalled. “WHOA! You guys! Holy cow!” the pastor started out, the boys looking at the pastor expectantly. “Do you know what, you guys? I totally know this. What you’ve created. It sounds so stellar to me. So similar. You have actually described the requirements of a super elite exclusive club of people.”

They just looked at the pastor, some of the boys starting to furrow their brows. Maybe the pastor was mad they’d also banned a fellow high school student, a frequent church volunteer and attendee who was known for speaking his mind. He had to go, too.

The pastor looked back at them, caught in a moment of heartbreak almost hinging into despair. What happened to all the lessons on God’s love, God’s acceptance? What of the Jesus who came to save the world? Hadn’t they heard a single one of the countless sermons the pastor had preached?

One of the boys cleared his throat.

“Are we like the KKK or something?”

“Yeah, well, or the Nazis,” the pastor affirmed, a lump in their throat.

The pastor took a deep breath and dived in, realizing that that night’s planned lesson would never be taught, because this was the moment, the moment when hatred and love diverged in the truth, and God was almost traded in for a cynical, violent bully. It wasn’t too late for these boys. The pastor loved these boys.

The pastor held their swelling tears at bay, kept a stoic face, asked the boys: “Do you really believe these things? Are you really racist? Sexist? Anti-Semitic?”

The pastor had been teaching them about the Bible for three years. “I was just heartbroken. Shocked,” the pastor told me. “It started out joking. Some of it came from a real place.”

The pastor pointed out to the boys that while they banned white individuals, they were quick to exclude entire groups of people who weren’t white. The boys, just teenagers, trusted the pastor enough that they kept going with the conversation. They stared at themselves in the mirror the pastor held up to them.

“They were able to name that it was racist. We talked about the KKK and the Nazis and about how these ideas were the same ones they have. And about how those groups (and so many others) acted on those hatreds. And what it did to the world.”

The boys stared down at their hands, hardworking hands, hands that held their mommies’ hands when they were dropped off at Kindergarten for the very first time, looking through eyes flocked by long, still-boyish eyelashes, eyes that held tears and sensitivities that—in this time in their lives—they were trying so desperately to hide away. They painted over their pain and love and emotions with the easily accessible white male hatred, asserting themselves at the top of the social order. Because the vulnerability required to do otherwise was impossible, now that they were becoming men. Someone would call them a “pussy.”

There were other influences, too, though. Dads and grandpas and pastors and moms and uncles and aunts and older kids. People who were gentle and kind no matter their gender. A church that had taught them of a God who loved first, who turned the other cheek.

They beseeched one another, admitting their culpability, grasping for their humanity, desperate for God to be God, for the relief of not having to make themselves into little white male demigods of guns and violence.

The pastor took a deep breath.

“The ultimate conclusion was that they were super glad that God was God. And God had done the creating, and not them,” the pastor told me, their eyes far-off again, remembering that day. “They were glad that they hadn’t done the creating, because they would have created something bad.”

The pastor first told me this story months before I began working in earnest on this book. But it never entirely left my mind, because it said so much in a single anecdote. These were the boys we didn’t think we had to worry about. It turned out that the hatred was latent in them, too. The creation story, fallen and thwarted and perverted by white men thirsty for power. Of course, the story didn’t end in that place, not this time. The story kept going, and I have to wonder if those boys didn’t think of it from time to time today while they raised their own sons. That group of Confirmation students allowed what could have been a devastation, a declaration of war and rage, to be a turning point, perhaps. It was a time to step back, to see and lament the ugliness within, offer it to God, and change.

Angela Denker is a veteran journalist and pastor in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. She has written articles for Sports Illustrated, the Washington Post, and Fortune and is the author of Red State Christians.

***

Interested in more on this topic? Check out episode 60 of The Revealer podcast: “The Rightwing Radicalization of White Christian Boys.”