How to Monetize Your Sex Scandal: A Guide for Disgraced Pastors

The rehabilitation of celebrity pastor Carl Lentz

(Pastor Carl Lentz. Image source: Sound of Heaven)

In an age when sex scandals among Christian clergy seem constant, disgraced ministers are fleeing to platforms more forgiving than the pulpit. In the case of former celebrity pastor Carl Lentz, that medium is podcasting. Last summer, after four years of apparently intolerable obscurity that followed his adultery scandal, the former megachurch leader of Hillsong NYC reemerged to peddle himself as a self-help influencer with messaging that had little connection to Christianity. With this new platform, he might just become the most successful disgraced preacher to stage such a comeback.

To be fair, Lentz rejects the label of “disgraced” that clung to him in the aftermath of his sex scandal. “I am more full of grace than I’ve ever been,” he insisted on the premiere episode of the podcast, which featured Lentz’s long-suffering wife, Laura, who had decided to forgive her adulterous spouse and support his new career. Eschewing the consequences of his hypocrisy, Lentz reclaimed his pastoral authority in the secular podcasting sphere.

Five years earlier, Brian Houston, the Australian co-founder of Hillsong Church, a non-denominational association of charismatic megachurches, announced that Lentz had been fired from Hillsong NYC because of “leadership issues and breaches of trust, plus a recent revelation of moral failures.” (Houston would resign a year and a half later following complaints from two women regarding inappropriate text messages and behavior, for which the minister blamed his use of sleeping pills, anti-anxiety medication, and alcohol. In 2023, Houston was also tried and acquitted of not reporting his late father, who had also been a minister, for sexually abusing several children.) Lentz’s moral failures likewise included inappropriate sexual behavior, most notably an affair with Muslim fashion designer Ranin Karim. The day after the news became public, Lentz posted an Instagram photo of his family—dressed in formalwear and holding hands—alongside a somber announcement of their departure from Hillsong and an admission of infidelity.

For a decade before the scandal, Lentz pastored New York’s hippest church. Although he technically shared the role of “co-pastor” with his wife, Lentz was the unequivocal leader of the movement. A former college basketball player with tattoos and a wardrobe of tight-fitting designer clothing, Lentz was charismatic, handsome, and magnetic—growing his congregation rapidly with both ordinary spiritual seekers and celebrities, such as NBA star Kevin Durant and pop idol Justin Bieber. (Lentz famously baptized Bieber in the bathtub of another NBA star, Tyson Chandler, in 2014.)

(Pastor Carl Lentz with Justin Bieber. Image source: IMDB)

Ever-invested in capitalizing on publicity, Lentz published a Christian self-help book in 2017. Rooted in watered-down prosperity gospel theology and pop psychology, Own the Moment promised to share principles that would help readers have an “impact” on the world. In reality, it was a collection of personal stories, likely exaggerated, that attempted to extract universal meaning from seemingly unremarkable situations. For instance, the book ends with an anecdote about a tourist who approaches Lentz and asks to take his picture because, she says, he looks like “somebody.” Lentz obliges, points her to a café that celebrities sometimes frequent, and concludes that it’s nice to make someone’s day brighter—even if for just a moment. There is no deeper lesson to be found.

One piece of wisdom from Lentz’s book did, however, turn out to be prophetic:

“The truth is that when you see a life implode from the outside—a public fallout, a marriage that ends in disaster—it can look like, ‘Wow, that happened overnight.’ It never does. It’s a slow erosion of principles, convictions, and standards that were allowed to drift and move, and nothing was done about it.”

By the time Lentz wrote this passage in 2017, Laura Lentz had already learned that her husband’s principles were not as morally grounded as his sermons made them sound. For years, the Lentzes had employed a live-in nanny, Leona Kimes, who was married to a future Hillsong Boston pastor and had children of her own. Still, in the name of sacrificial service to the church, she spent most of her time in New York helping the celebrity pastor’s family, while a nanny helped raise her children. Eventually, the relationship between Leona and Carl Lentz became sexual.

According to an investigative report leaked to the Christian Post in the aftermath of Lentz’s dismissal, the pastor admitted to partaking in “pretty much everything you can do” short of oral sex and intercourse. Kimes, for her part, would later characterize the relationship as sexual abuse. In 2016, Laura discovered her husband and Kimes in a compromising position and, in a fit of rage, punched Kimes several times. The pastor then managed to convince Laura that what she had witnessed was, in fact, innocent. Things in the Lentz household resumed as usual.

Lentz’s “usual” reportedly included other instances of infidelity, along with sexually manipulative behavior. According to multiple former members of Hillsong NYC, these abuses of power permeated every part of the ministry—from status-based discrimination in the pews (the tabernacle had a separate V.I.P. area for celebrity attendees) to inappropriate sexual behavior by other men in leadership, who maintained their positions despite complaints from church volunteers.

Lentz has addressed few of these complaints despite having multiple opportunities to respond to the allegations. In 2023, he appeared in the FX docuseries The Secrets of Hillsong. Attempting to garner the public’s sympathy, Lentz discussed his ADHD diagnosis and admitted to occasionally taking more medication than prescribed. He also disclosed abuse he had suffered at the hands of a family friend as a child, saying it led him to develop a “pattern of secrecy” that would come to dictate much of his conduct.

In the immediate aftermath of the scandal, Lentz entered outpatient treatment for depression, anxiety, and pastoral burnout. Later, he found a therapist, Dr. Alex Katehakis, whom he credits with helping him put his life back together. Katehakis, who was the first non-family member to appear on Lentz’s podcast, specializes in human sexuality. She taught Lentz that his sexual addiction likely stemmed from childhood trauma and reassured him that the clinical label of “narcissistic personality disorder” did not technically apply to him. Addressing both Lentz and his wife (who, post-Hillsong, describes herself as “speaker, podcast host, interior designer, storyteller, visionary, and empowerer of change”), Katehakis said, “Both of you—myself included—have a healthy narcissism, or we wouldn’t have the success that we have.” With a clean bill of mental health, Lentz now says he is eager, through the medium of podcasting, to help others face their problems head-on and live up to their potential.

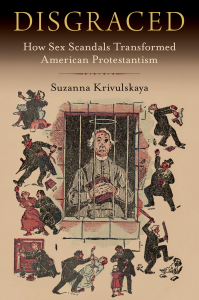

Lentz believes he is entitled to reclaim his public platform. This conviction is informed by at least two forces: the manosphere’s denunciations of (the myth of) cancel culture and a culmination of generations-long efforts by—pardon the term—disgraced pastors to reclaim their power. As I show in my book Disgraced: How Sex Scandals Transformed American Protestantism, scandal-prone evangelical ministers over the past several generations have been remarkably successful at minimizing their transgressions in order to return to the pulpit. Whether or not Lentz is a conscious student of this history, he stands on the metaphorical shoulders of some of the most entrepreneurial fallen leaders in American Christianity. Though he does not explicitly invoke their legacy, several prominent disgraced evangelists from the recent past provide a roadmap for making a return to public ministry away from organized religion—with its occasional demands for meaningful accountability.

Lentz believes he is entitled to reclaim his public platform. This conviction is informed by at least two forces: the manosphere’s denunciations of (the myth of) cancel culture and a culmination of generations-long efforts by—pardon the term—disgraced pastors to reclaim their power. As I show in my book Disgraced: How Sex Scandals Transformed American Protestantism, scandal-prone evangelical ministers over the past several generations have been remarkably successful at minimizing their transgressions in order to return to the pulpit. Whether or not Lentz is a conscious student of this history, he stands on the metaphorical shoulders of some of the most entrepreneurial fallen leaders in American Christianity. Though he does not explicitly invoke their legacy, several prominent disgraced evangelists from the recent past provide a roadmap for making a return to public ministry away from organized religion—with its occasional demands for meaningful accountability.

In 1976, Billy James Hargis was at the height of his fame and influence—having built a religious media empire and founded a Christian college—when Time magazine published an exposé revealing that several college students, notably of both genders, had accused Hargis of sexual impropriety. In the wake of the scandal and the subsequent investigation by the Tulsa district attorney, Hargis decried fellow Christians for not standing by him, repeatedly called himself a sinner (falling intentionally short of specifying the nature of his sin), and pointed to his wife and children as the ultimate victims of public scrutiny.

Although the scandal shut down Hargis’s college, his career did not end. In the early 1980s, Hargis published a memoir, which he titled My Great Mistake. Despite the title, however, the book focused on the project of redemption—not on honest reckoning. Hargis’s mistake, he argued, was being too trusting of fellow Christians, not any matter of sexual misconduct. Though diminished, Hargis’s ministry continued through regular radio broadcasts and the Christian Crusade newspaper, which he published until his death in 2004.

Ten years after the public learned about Hargis’s extracurricular pursuits, another high-profile preacher watched his reputation unravel. Jim Bakker was a charismatic televangelist who, like Lentz, built his brand on accessible messaging and compelling personal delivery. Bakker and his wife Tammy Faye created a thriving Christian broadcasting empire, whose proceeds funded a lifestyle so lavish that local North Carolina reporters were compelled to investigate the family’s finances. What they uncovered, beyond fraud and financial mismanagement, was a secret $265,000 payment made to Jessica Hahn, a young church secretary. Seven years before the scandal broke, in 1980, Bakker had met Hahn in Florida, where she had flown from New York to help watch the minister’s children while he hosted a fundraiser. What happened in the hotel room where they met remains a matter of debate. Hahn’s testimony suggests she was sexually assaulted by the pastor; Bakker has insisted that the encounter was consensual.

The Hahn revelation scandalized the public but did not immediately move the Assemblies of God, Bakker’s denomination, to defrock him. Initially, they hoped Bakker’s restoration was imminent. Instead, other revelations of sexual impropriety—including with men—forced them to sever ties with the minister. Secular authorities were no more magnanimous; the judge in Bakker’s fraud trial famously declared that “those of us who do have a religion are sick of being saps for money-grubbing preachers and priests” and sentenced him to a hefty fine and forty-five years in prison. The judge’s hostile comment eventually led to a new sentencing hearing, which significantly reduced the term. Bakker was paroled in 1994.

Two years later, Bakker published a book, promisingly titled I Was Wrong. In the end, however, the book—just like Hargis’s My Great Mistake—was not an apology for poor behavior but an attempt at redemption. Bakker denied the accusations of sexual assault, minimized his guilt in the fraudulent fundraising operations, and rejected rumors of homosexuality and bisexuality. Like Lentz, Bakker revealed that he had been sexually abused as a child. And like Lentz, he began seeing a therapist, with whom he shared his experiences and even pondered whether he was gay. “No, Jim, you are not a homosexual,” the therapist reportedly assured him. “No man can love women as much as you do and be a homosexual. It is obvious you’re not gay.”

With speculations of queerness set aside, Bakker explained the significance of the book’s title in the final lines of the monograph: “I once thought that God had abandoned me. I thought that my days of ministering for the Lord were done. I thought that I would never preach again. I was wrong.” Bakker returned to full-time ministry in 2003. Despite a much-reduced following, he continues to make headlines: perpetually on the brink of bankruptcy, he pleads for donations, spreads COVID misinformation, and sells doomsday prepping merchandise.

Obfuscation and deflection have served disgraced Christian ministers well. With aspirations of tapping into revenue streams akin to the highest grossing podcasts of Mel Robbins and Joe Rogan, Lentz has relegated Christianity to the margins of his broader media project. The goal of Lentz’s new venture is not to proselytize but, he says, to help others prosper using the lessons of his sex scandal and subsequent recovery.

The most successful podcasters are white, straight, conservative-leaning men, who denounce all manner of tradition. They dismiss mainstream media as biased, adopt an informal conversational tone, and celebrate the virtues of libertarianism alongside what they describe as “free”—and their critics label conspiratorial—thinking. Having transitioned from evangelizing to influencing, Lentz should have no problem attracting a sizable audience. And, given the industry’s growing revenue, he is poised to be more financially successful at monetizing his scandal than most of his predecessors. Admittedly, Christianity has often been incidental to fallen preachers’ redemption. Lentz may just perfect the art of turning disgrace into dividends.

Suzanna Krivulskaya is Associate Professor of History at California State University San Marcos and author of Disgraced: How Sex Scandals Transformed American Evangelicalism. Her research and public scholarship examine how religion, gender, and sexuality intersect in United States history.

***

Interested in more on this topic? Check out episode 61 of The Revealer podcast: “Protestant Sex Scandals in America.”