Americans Leaving Religion

An excerpt from “Goodbye Religion: The Causes and Consequences of Secularization”

(Image source: Sébastien Thibault/Katie Couric Media)

The following excerpt comes from Goodbye Religion: The Causes and Consequences of Secularization (NYU Press, 2024). The book examines why so many Americans are leaving religion and what that means for the country.

This excerpt comes from the book’s conclusion.

***

Why are more American’s leaving religion? It varies from person to person. In fact, for any group of individuals, the reason(s) could be wildly different. A gay individual may leave because their religion rejects a core part of their self-identity, their sexuality. A woman may leave because she is fed up with the misogyny, patriarchy, and general status quo of her religion. Someone else might leave because they desire more autonomy in what they believe and what they will teach to their children. Yet another may run into internal conflict over their modern understanding of the universe and what their religion teaches. Still others may leave because they’re just bored and want to do other things. There are myriad other reasons that both push people away from religion and pull them toward a more secular life.

In the years of research we put into our book Goodbye Religion, we discovered that it’s very, very difficult to predict why any one individual will leave. As we thought about this fact, we happened upon a metaphor that we think may be helpful to those who are trying to understand the phenomenon of religious exiting. Imagine a giant pool surrounded by cliffs of varying sizes. Standing on the cliffs above the pool are people of all stripes. The pool represents secularity—a life without religion. The cliffs represent religiosity.

In the years of research we put into our book Goodbye Religion, we discovered that it’s very, very difficult to predict why any one individual will leave. As we thought about this fact, we happened upon a metaphor that we think may be helpful to those who are trying to understand the phenomenon of religious exiting. Imagine a giant pool surrounded by cliffs of varying sizes. Standing on the cliffs above the pool are people of all stripes. The pool represents secularity—a life without religion. The cliffs represent religiosity.

The lowest cliffs are the lowest-cost religions. Some cliffs are just a foot or two above the level of the pool (e.g., Episcopalians), and others have slides directly into the pool (e.g., Unitarian Universalists). For the individuals on these cliffs, getting into the pool is so easy that it’s almost like nothing has changed. Many of their friends are already in the pool and doing just fine. Continuing to hang out on the cliff as more of their compatriots leave makes less and less sense. As more people enter the pool, the level of the water rises and eventually swamps some of the cliffs for the lowest cost religions, making it so that those who haven’t jumped eventually find themselves standing in the pool as it overruns their cliff.

The highest cliffs are the highest-cost religions (e.g., Amish, Pentecostalism, Scientology, etc.). Jumping from some of those cliffs takes a great deal of courage as the pool is very far below them and very few people are jumping. In fact, some cliffs are so tall that the people on them can’t actually see the pool, as they are above the clouds. Should individuals on those cliffs choose to jump, they would literally be jumping into the unknown. Yet, people are doing so knowing that they could very well be jumping to their deaths. Jumping from such a height means it likely takes them longer to surface after hitting the water, and it’s a bit of a struggle, but most eventually do surface, make friends, and learn how to be with others in the pool.

Of course, there are lots of other cliffs in the mid-range (e.g., Catholics, Southern Baptists, etc.). These cliffs are tall enough that individuals have to jump in the pool, but not so tall that they can’t see the pool. And, as more people jump, the pool level continues to rise, reducing the risk of jumping. As we mentioned, which individuals will take the risk is very difficult to predict. There are a few factors that increase the odds, but there are no perfect predictors. Some people are naturally risk-averse and want nothing to do with the cliff face, let alone the pool below it. Others don’t even hesitate, regardless of the height of the cliff. They would rather be anywhere than on the cliff. Some hold hands and jump together. Others take the plunge alone and worry about how those on the cliff will view what they have done. Some are more reticent to jump until a friend who has already done so yells up and tells them that the water is not only fine, but that they’re enjoying their new life in the pool. There is so much natural human diversity that it is just difficult to predict who will jump, let alone why.

Even so, the pool has always been there and, during certain periods of human history, it was only those most willing to take the risk who were willing to jump. But the pool has gotten cleaner, warmer, and deeper over time (in addition to the survey data we use in our book, we offer the stories of more than a hundred religious exiters to bolster this claim). Of course, that is not how religious leaders describe it. They call it a cesspool, and warn people that jumping into the pool will lead to pain, suffering, emptiness, meaninglessness, and possibly even death. Yet, as the level of the pool rises, the description provided by many religious leaders is harder to maintain as more of the people on the cliffs can see the pool and all the people in it.

As more people leap from the cliffs, it is becoming more welcoming and there are more people to help the newcomers adjust to life in the pool. It’s easier to jump into the pool today than it ever has been and it seems likely to continue to become easier, even though some feel the need or experience pressure to climb to ever higher cliffs to make it harder to jump. The water is rising. The pool is welcoming. Eventually, the pool will get so full that even those on the highest cliffs won’t have that far to jump.

(Image created by Dall-E)

Of course, life in the pool isn’t anything like perfect, and it’s definitely not for everyone. Some people need some swim lessons after they jump, and there will be some people in the pool who are exhibiting bad behaviors. The pool is not a utopia. People continue to have their struggles, some people still cheat, lie, and commit violent crimes. People get sick, people fight, and people die. The secular pool is not the answer to all of life’s problems or questions. It’s just a different place that is not on top of a cliff, and it is just fine.

That’s our (imperfect) metaphor for understanding why people exit religion. We cannot perfectly predict which individuals will leave or why, but we know there are some factors that predispose people to leave—the push and pull factors we mentioned—plus a changing cultural environment that makes it easier to leave.

What’s Next for Religious Exiting in the U.S?

What does the future hold for religious exiting and the growth of the nonreligious? We are social scientists, not prophets. We are not and should not be in the business of telling others what the future will bring. But . . . social science does allow for reasonable predictions with lots of caveats and conditions. Also, we’re not the only ones to project the growth of the nonreligious into the future. In a 2022 study, Pew developed their own projections for the religious makeup of the US, which we’ll describe in more detail below.

We’re going to be extremely cautious here with our projections. Previous scholars who have suggested that religion was going to decline dramatically or completely disappear have been shown to be wrong and are now legitimately criticized. As a result, we’re not going to make such a suggestion. Also, we’re going to be rather conservative and only project to 2040.

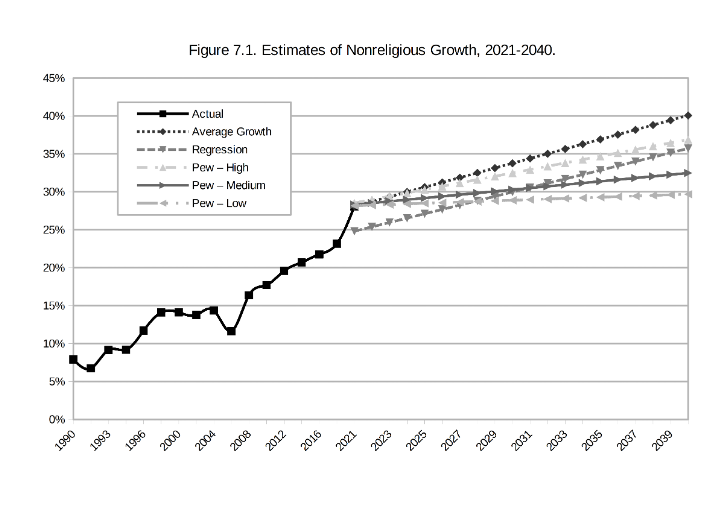

Keeping in mind that all such projections are heavily qualified and contingent, we are going to offer some possible futures for the US religious landscape. Figure 7.1 shows the percentage of the US population that reported no religious affiliation from 1990 through 2021, based on the General Social Survey, using a solid black line. Those are not projections but the actual survey results. In 1990, 9% of US adults reported no religious affiliation; in 2021 it was 28%. The 2021 wave of the GSS was the latest wave available when we were writing this book. Everything after that point is a projection of the growth of the nonreligious into the future. We provide 5 estimates—2 of our own and 3 from the previously mentioned Pew study.

Keeping in mind that all such projections are heavily qualified and contingent, we are going to offer some possible futures for the US religious landscape. Figure 7.1 shows the percentage of the US population that reported no religious affiliation from 1990 through 2021, based on the General Social Survey, using a solid black line. Those are not projections but the actual survey results. In 1990, 9% of US adults reported no religious affiliation; in 2021 it was 28%. The 2021 wave of the GSS was the latest wave available when we were writing this book. Everything after that point is a projection of the growth of the nonreligious into the future. We provide 5 estimates—2 of our own and 3 from the previously mentioned Pew study.

First, Pew’s estimates include a number of important elements. They included demographic variables in their models, recognizing, for instance, that the religious tend to have more kids than the nonreligious. As a result, the religious have the potential for more growth because they are having more children, though the religious are less likely to retain their children than are those with no religious affiliation, so the net flow is away from religion at present. The various estimates by Pew also make certain assumptions. The low model assumes that no person in the US will change their religion after 2020, which is, of course, not particularly plausible. But that assumption does provide a baseline of what could happen should demographic inertia continue into the future. Assuming that there is no more religious exiting in the US, just the continued inertia of nonreligious people raising their kids without religion, that will still result in a very slight uptick in the percentage of the population that has no affiliation through 2040, from 28% to 29%. The mid-level projection by Pew assumes that the switching (really, exiting) that is currently taking place will continue into the future. Under that assumption, Pew projects the nonreligious to grow to about 32% of the US population through 2040, which really isn’t that much growth in light of recent past growth. Finally, Pew’s high-growth model assumes that the rates of switching (i.e., exiting) will increase, which would result in the nonreligious making up about 36% of the US population by 2040.

We added two models to the three by Pew, both of which use radically simplified assumptions. First, we took the average growth of the nonreligious per year from 1990 to 2021, around .6%, and projected that into the future. That results in the highest estimate in our figure, around 40% of the US population being nonreligious by 2040. Our second model used a statistical technique called regression to allow us to project the population that would be nonreligious in 2040: 36%.

While the two projections we have added are very simple, they reflect some basic assumptions. To make those assumptions explicit, our projections can be thought of as reflecting the same social forces that contributed to the increase in religious exiting from 1990 to 2021. In other words, whatever social forces drove people out of religion from that time period resulted in (a) an average rate of religious exiting and/or (b) a general trend in religious exiting. If we assume that the social forces driving religious exiting from 1990 to 2021 continue to be in effect through 2040, then it’s plausible that the rate of religious exiting will continue apace. Of course, those forces could change. As we noted, our models are predictions based on certain assumptions, not prophesies. We are not saying what will happen, only what could happen should certain assumptions hold true.

This leads to one final point here. While we think Pew’s baseline model, in which religious exiting basically plateaus, is unlikely (as do they) and the other projections are more likely, it is also worth mentioning that both our slightly higher projections and Pew’s high-switching projection could actually underestimate religious exiting in the coming years. It is possible— note our switch from “plausible” to “possible” —that religious exiting and having no religious affiliation are effectively social innovations, like the adoption of CDs over cassettes, or DVDs over VHS tapes, or smart phones or even electric cars. When technological advances take place, there is often a slow build-up at the beginning, when early adopters are really the only ones who are willing to take the risk of adopting the new technology. Once acceptance of the technology hits a certain level in the population, then it becomes more widely accepted and adoption accelerates rapidly, only to plateau once it reaches nearly complete saturation. Effectively, innovations follow an S-shaped curve—slow growth at the beginning, rapid growth in the middle, and slow growth at the end. This can be seen with cell phones. At the beginning, cell phones were expensive and buggy, and were only adopted by a select few. But the spread continued until it hit an inflection point (usually somewhere in the 20% to 30% range). Once enough innovators had purchased cell phones and they were reliable enough, the rate of adoption accelerated until almost everyone had one. There are, of course, still some people who have not switched to a cell phone, but they are increasingly rare.

We realize it might sound strange to compare cell phone adoption with people leaving religion. But in terms of making projections, it’s possible that religious exiting could actually follow a similar path, with relatively slow growth for a while, followed by an inflection point when this nonreligious innovation begins to spread rapidly, only to plateau at some point in the future with a minority of individuals remaining religious indefinitely. We are not arguing that an S-shaped curve is more likely than the projections we laid out, only that we and Pew could be wrong and could underestimate the rate of growth of the nonreligious in the US. There is another factor that is important to note as well—older people are substantially more likely to report a religious affiliation than younger people. Thus, in addition to people leaving religions and people being raised without a religious affiliation, those most likely to report a religious affiliation are literally being removed from the population at higher rates through death. As a result, the transition from a predominantly religiously affiliated society in the US to a predominantly secular society may increase through all three social forces—exiting, retention of young people, and the death of the elderly. As a result, the percentage of the US population reporting no religious affiliation is likely to continue increasing at a relatively quick pace for the foreseeable future.

Finally, astute readers will have noted that we began referencing the nonreligious in general, which includes not just those who have exited religions, but also those who were raised with no religion. We did that primarily so we could draw on Pew’s projections, since they did not separate out these two groups. But it is not all that complicated to think about how those two groups will shift over time. At present, the majority of Americans report a religious affiliation, which means there are more people who can and will exit religion than there are people who will be raised without a religious affiliation. Eventually, that will probably change such that there are more people who are raised without a religious affiliation among the nonreligious than there are people who left religion, but that is decades into the future.

We can quibble over details or try to make very precise projections for the future of religious exiting in the US. But we think it actually makes more sense to simply note that, should current conditions continue through 2040, we would genuinely be surprised if the percentage of the US population that exits religion did not continue to increase. As we make clear in our book, we do not think religion will disappear from the American landscape. There will, in all likelihood, still be many Americans who both claim and practice a religion in 2040 and beyond. However, as we argue in Goodbye Religion, the evidence shows that many more Americans have jumped from their religious cliffs – however high they were – and entered the pool of secularity. Leaving religion didn’t ruin their lives, and we should be much less worried about the pool rising than we have been so far.

Ryan T. Cragun is Professor of Sociology at the University of Tampa and coauthor of Beyond Doubt: The Secularization of Society.

Jesse M. Smith is Associate Professor of Sociology at Western Michigan University and coeditor of Secularity and Nonreligion in North America.