Gender and the Black Church Today

An excerpt from “The Contemporary Black Church: The New Dynamics of African American Religion”

(Image source: Gardner-Webb University)

The following excerpt comes from Jason E. Shelton’s The Contemporary Black Church: The New Dynamics of African American Religion (NYU Press, 2024). The book explores the increasing religious diversification among Black Americans as well as the significant increase in Black Americans with no religious affiliation.

This excerpt comes from the book’s fifth chapter, “Are all sins created equal?”

***

A Woman’s Place is in the Home?

Speaking of debates in society, changing expectations for women and men both inside and outside of family life has become a highly contentious issue. For most of American history, conventional wisdom has held that men go to work to provide for their family, while women do not work but care for the home and raise children. This is the classic ideal of the breadwinner/homemaker model. While this archetype was never applicable to most African Americans (since neither black men nor women were granted access to the kinds of opportunities that permitted such a privileged lifestyle), it is true that African Americans’ beliefs about the role of women have changed. In the late 1970s, 61% of black GSS respondents either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with the following statement: “It is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.” Thirty-nine percent “disagreed” or “strongly disagreed.” However, by the late 2010s, only 25% of study participants at least agreed with the statement, while 76% at least disagreed. This dramatic shift is further evidence of previously discussed changes in African American families over the past half-century.

Speaking of debates in society, changing expectations for women and men both inside and outside of family life has become a highly contentious issue. For most of American history, conventional wisdom has held that men go to work to provide for their family, while women do not work but care for the home and raise children. This is the classic ideal of the breadwinner/homemaker model. While this archetype was never applicable to most African Americans (since neither black men nor women were granted access to the kinds of opportunities that permitted such a privileged lifestyle), it is true that African Americans’ beliefs about the role of women have changed. In the late 1970s, 61% of black GSS respondents either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with the following statement: “It is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.” Thirty-nine percent “disagreed” or “strongly disagreed.” However, by the late 2010s, only 25% of study participants at least agreed with the statement, while 76% at least disagreed. This dramatic shift is further evidence of previously discussed changes in African American families over the past half-century.

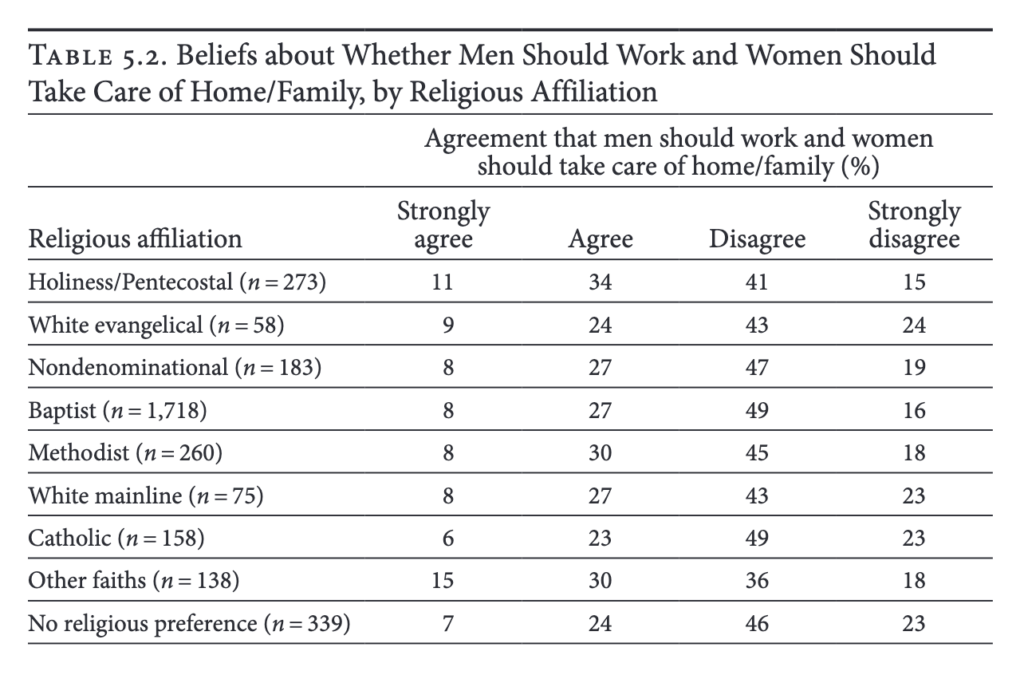

Which denominational families most strongly emphasize the breadwinner/homemaker model? Table 2 shows that at least 56% of members of all traditions comprising the contemporary Black Church do not believe that a woman’s place is in the home. However, multivariate results indicate that Baptists, Methodists and Catholics are more likely to disagree than non-denoms. Moreover, Methodists and Catholics differ from Holiness/Pentecostals, but Baptists to do not. Taken together, these findings indicate that mainliners are more significantly opposed to the statement than evangelicals. Interestingly, Holiness/Pentecostals and non-denoms do not differ from religious non-affiliates in their beliefs about whether women should take care of home and family (however, Baptists, Methodists, and Catholics do). These latter findings suggest high levels of social conservativism among African American “nones.”

Additional findings from the GSS confirm the mainline versus evangelical divide in beliefs about traditional gender roles. For instance, Methodists are less likely than non-denoms to believe that preschool children “suffer” if their mother works outside of the home. Moreover, Catholics are more likely than Holiness/Pentecostals to: (a) believe that working mothers can establish relationships with their children that are just as “warm and secure” as mothers who don’t work, and (b) vote for a woman to become President of the United States so long as she is “qualified” for the position. It is also worth mentioning that: (c) Baptists, Methodists, and Catholics are less likely than non-affiliates to believe that children suffer if their mother works outside of the home (although evangelicals do not differ from the “nones”), and (d) Baptists, Catholics, and non-denoms are more likely to vote for a female President than religious non-affiliates. These latter findings further attest to high levels of social conservativism among African American religious non-affiliates. This is most likely because black men comprise the bulk of the GSS sample of religious “nones.”

Additional findings from the GSS confirm the mainline versus evangelical divide in beliefs about traditional gender roles. For instance, Methodists are less likely than non-denoms to believe that preschool children “suffer” if their mother works outside of the home. Moreover, Catholics are more likely than Holiness/Pentecostals to: (a) believe that working mothers can establish relationships with their children that are just as “warm and secure” as mothers who don’t work, and (b) vote for a woman to become President of the United States so long as she is “qualified” for the position. It is also worth mentioning that: (c) Baptists, Methodists, and Catholics are less likely than non-affiliates to believe that children suffer if their mother works outside of the home (although evangelicals do not differ from the “nones”), and (d) Baptists, Catholics, and non-denoms are more likely to vote for a female President than religious non-affiliates. These latter findings further attest to high levels of social conservativism among African American religious non-affiliates. This is most likely because black men comprise the bulk of the GSS sample of religious “nones.”

By now, you’ve probably noticed that the multivariate statistical results for Baptists more closely parallel those of mainline rather than evangelical Protestant traditions. This precisely explains why I argue that the black Baptist family is best understood as a mainline tradition within the contemporary Black Church. However, most of the high-ranking Baptist clergy that I spoke with reinforced traditional views about the role of women, and specifically referenced the breadwinner/homemaker model. For example, Pastor Lewis explained his views in a very straightforward and reasoned way:

“Historically, this country has promoted men as the providers, and I think that is biblical. Up until about 25 years ago, most of the denominations would basically line up with that.

However, there’s been a shift, and now most would say it takes two working people to make your household operate and fulfill the goals that you as a couple would like to fulfill as a family.

As a result, if you and your husband have agreed that this is the way your family will need to operate to meet your goals as a family unit, then there’s nothing wrong with the wife working outside of the home, helping to achieve those goals. It’s a mutual commitment and agreement on the part of the husband and wife. More of us embrace that kind of approach to family units today than ever before.

I believe, though, that there is a kind of a narrow, Bible-believing evangelical, who would be more rigid to still say the husband is the one that goes out and earns the living for his family and the wife should stay home because God intended her to be the nurturer of the children and organizing the home. I subscribe to that belief.”

Interestingly, my results for non-denoms and Holiness/Pentecostals also suggest a discrepancy between clergy and laity. While the Baptist clergy that I interviewed are seemingly more conservative on traditional gender roles than laity in the GSS, the non-denom and Holiness/Pentecostal clergy that I interviewed are somewhat more liberal on gender roles than laity. For example, Pastor Forbes does not believe that a woman’s place is in the home. To the contrary, he feels that women must have “economic viability in this capitalistic society”:

“The more I read biblical text it subscribes to a woman who is working and the philosophy of her work is to take care of her kids, answer for her man, and to support her household.

In the Bible there are women entrepreneurs and there are businesswomen. So I think there’s something to be said for giving the woman freedom to have economic viability in this capitalistic society. If we are talking about being a blessing to others, our families and community, then sometimes the gift of that is not just on the man. It’s on the woman as well. Instead of fighting an economic fight one-handed you might as well become ambidextrous! God has given us both a right-hand and left-hand! (laughter)

During times of war, while the men are away fighting for our country the women are working to make sure that they had a country to come home to. You can’t just use women for one thing but not acknowledge them for all things.”

Elder Harris might agree with some of Pastor Forbes’ assertions. The following statement not only suggests that his own personal position on traditional gender roles has changed over the years, but so has that of other high-ranking clergy within COGIC:

“You know what I’m finding? Even in a tradition like mine that tends to be more biblio-centric, there are questions about the roles of males and females. An interesting point about the Church of God in Christ is that early-on Bishop Mason empowered women by creating a Women’s Department where they had certain leadership roles in the denomination. And when you attend a large meeting of the Church of God in Christ, it’s kind of the father/mother thing in that you have the men on one side of the stage and women on the other. In one sense, they are both equally on the stage even though the men have more authority.

Black families have always struggled in our situation here in America. One result of that is there have been women leaders in the Church of God in Christ, and we have more-and-more women leaders today.

There’s a group called ‘COGIC Scholars’ that has discussions about whether we should continue to hold on to the same kind of views about women in leadership as the past generation. There’s a practical sense in society that women can be positive leaders, and there has been more of an opening for women having prominent leadership. This is happening at a time when men are trying to hold on to leadership, although there’s a movement towards greater equality within the home.”

While there are signs of shifting tides among evangelicals, waves of changing beliefs about the role of women crashed onto mainline shores decades ago. Most of the high-ranking mainline clergy that I spoke with emphasized one of two points: (1) that women have been subjugated within our nation overall and inside of African American Christianity, as well as (2) women and men must be treated fairly. Many of them also (3) provided examples to support their arguments. For example, Pastor White feels that many people misunderstand that God created Adam and Eve to be “co-equal”:

“God made men and women in His image. There wasn’t a pecking order until Satan, the enemy, came in and tried to disarrange things.

God did not make Eve from Adam’s head because she would think she’s above him. God did not make Eve from Adam’s feet because then he would step on her. God made Eve from Adam’s rib, where she walks beside him. So, I think men and women are co-equal.

However, God told Adam to dress and keep the garden, but Eve to be a helpmate not a hurt-mate. So I believe families who teach this lesson have a tendency to tell women: ‘You can stay home and raise the children but at the same time that doesn’t mean you don’t do any housework.’”

Rev. Brown also emphasized gender equality. However, he did so by recalling a discussion that took place between himself and the pastor presiding over his daughter’s wedding. Rev. Brown and his family were very concerned about what they view as sexist themes within traditional marriage vows. Among other things, he did not want to reinforce the perception of his daughter as her soon-to-be husband’s “property.” The following narrative was conveyed in a cheerful and funny tone, but Rev. Brown’s point is very serious:

“So, we’re going through a pre-ceremony walk-through. I said to the minister who was going to marry my daughter, ‘Let me ask you a question. When you do the vows and you say the repeat after me thing, are you going to ask: Who gives this woman?’

The minister responded, ‘Yes.’ That’s when I said, ‘You’re going to have a problem!’ (laughter)

I said, ‘First off, none of my daughters are property so they can’t be given to anybody. And, if you get up there in front of these people and ask, ‘Who gives this woman?,’ the women in my family are gonna attack you! I guarantee it! (laughter) And don’t be looking at me for help cause I’m trying to clue you in right now! (laughter)

I told him that he should ask the congregation, ‘Who presents this woman?’ But don’t be talking about “giving nothing away” cause ain’t nobody owning nothing around here.

He was taken aback, but he did take the counsel and didn’t try to ‘give my daughter away.’ If he had, I know at least three of the women in that church would have chewed his butt up!”

Speaking of women in the Church, the high-ranking mainline clergy with whom I spoke were critical of sexism in society and within the pastorate. For instance, Rev. Dr. Spencer believes that some traditional views of women are out-of-step with the modern world, and also undermine the significant role that black women have played in sustaining black families over the centuries. Furthermore, she believes that a “toxic masculinity” continues to hold back women within African American Christianity:

“People cherry-pick scriptures that fit their take on the Bible and personal lifestyle. In the Bible there were businesswomen, women were the first ones to Christ’s tomb, women were at the foot of the Cross, and actively involved in the Old Testament and New Testament in terms of their presence in ministry as leaders.

So at this point in time, trying to put women down with some kind of archaic, chauvinistic, misogynistic, toxic masculinity perspective is not okay. Both then and now, if the woman didn’t work and take care of home there would be no “black family.”

Any black man that comes with that old traditional stuff has to leave that in the 1950s. Leave It To Beaver is not on tv anymore! We are in the 21st century! Some of this stuff is ridiculous!

And it’s especially difficult for clergywomen in the Bible Belt. Supposedly, women should not be in leadership, can’t be in the pulpit, and can only teach during Sunday School. That makes no kind of sense.”

Rev. Dr. Strong would completely agree with Rev. Dr. Spencer. She, too, recognizes “patriarchy” within African American Christianity. However, her point moves in a slightly different direction by focusing on women’s response to sexism within the faith, as well as a new sense of individualism that took root in Black America during the 1960s and 70s. It’s worth mentioning that her view closely aligns with mainliners’ attention to an individual locus of moral authority:

“Women were shushed! We were told to “respect your elders” and that whole patriarchy thing ran rampant.

These men were abusing their power but then women started to get the word that they didn’t have to go along with stuff—even if it’s an abusive husband who the Bible says they are supposed to follow.

Those women started to hear their own voices in the 1960s and 70s, and honoring their own voices gave them the ability to question, decide to not go along with things, leave the Church if they could—or if they dared.”

Jason E. Shelton is Professor of Sociology and Director of the Center for African American Studies at the University of Texas at Arlington and the author of Blacks and Whites in Christian America: How Racial Discrimination Shapes Religious Convictions.

***

Interested in more on this topic? Check out episode 52 of the Revealer podcast: “The Changing Black Church.”