More than Missionary

Abortion On Demand

The surprising history of a politically charged phrase

(Image source: Getty Images)

This past February, President Joe Biden offered a muddled statement on abortion. He disavowed “abortion on demand” because he’s a “practicing Catholic” but maintained that “Roe v Wade was right.” The President’s statement spurred a flurry of commentary that puzzled over his position on abortion and what he meant by the phrase “abortion on demand.”

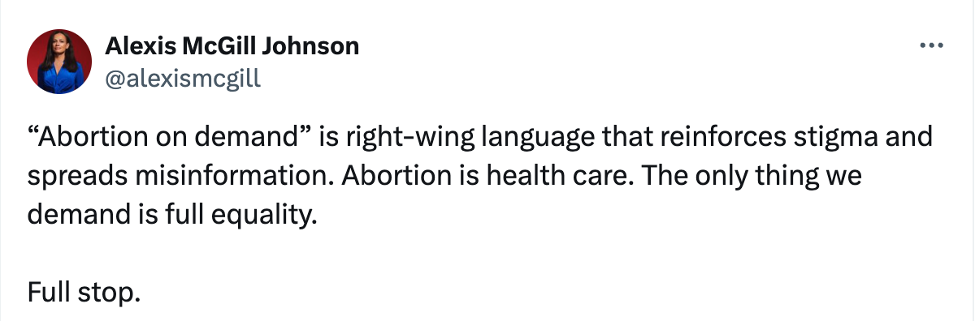

While Biden’s tepid support of abortion rights has been apparent for years, the meaning of “abortion on demand” is less so. Some respondents, like the President of Planned Parenthood, condemned the phrase as “right-wing language.” More nuanced analyses note that the phrase “abortion on demand” originated with abortion rights activists and only later became a conservative phrase to repudiate abortion.

Yet, both perspectives misunderstand the more complicated political history of “abortion on demand” and its connections to religion in general and Catholicism in particular. Moreover, they miss out on the fact that the denigration of “abortion on demand” was and remains rooted in sexism that has spanned religious denominations, political affiliations, and both the anti-abortion and abortion rights movements.

Yet, both perspectives misunderstand the more complicated political history of “abortion on demand” and its connections to religion in general and Catholicism in particular. Moreover, they miss out on the fact that the denigration of “abortion on demand” was and remains rooted in sexism that has spanned religious denominations, political affiliations, and both the anti-abortion and abortion rights movements.

A primer on the term’s complicated history is necessary, not just to understand President Biden’s utterances, but to better navigate the post-Dobbs landscape.

For over six decades, the struggle over the meaning of “abortion on demand” has reflected the fight over men’s ability to control women’s reproductive lives. In the early 1960s, state legislatures began to reconsider abortion restrictions amidst revelations of the high rates of criminal abortions and in the wake of thalidomide and rubella scares, which led to birth defects and infant deaths. Male medical experts, legal reformers, allied professionals, and religious leaders had an outsized voice in popularizing and shaping the meaning of “abortion on demand” – a phrase so foreign it needed to be put into quotations in expert and popular literature.

Media coverage in the early 1960s linked the foreignness of “abortion on demand” with actual foreign countries’ abortion policies. Japan, Hungary, and the Soviet Union were go-to examples because they permitted elective abortions. American commentators believed the United States was unlikely to adopt such alien practices. Such was the case in 1962, in discussions of the popular book The Abortionist by Lucy Freeman, which saw one of the earliest variations of this phrase in the American press. Amidst Cold War xenophobia, these foreign associations did little to help make the case for abortion on demand in the United States.

The landscape of reproductive rights, however, was rapidly shifting, and the foreign associations of abortion on demand would soon overlap with domestic debates within the growing American abortion rights movement. At first, the abortion rights movement was male-dominated and made up of “small, well-defined groups of elite professionals: public health officials, crusading attorneys, and prominent physicians.” By the mid-1960s, there were two major camps in the abortion rights movement: reformers and repealers. It was these two camps’ division over policy that would play a crucial role in shaping the political meaning of abortion on demand for decades to come.

The difference between supporters of reform and repeal was the degree of change they envisioned to abortion laws. Reformers called for a limited set of exceptions to these restrictions so that “deserving” women could access abortion. Rape, incest, fetal deformity, and the health and life of the mother, they believed, were among the grounds for terminating pregnancies. Repealers, meanwhile, wanted abortion to be elective—a private decision made by any woman for any reason. Abortion rights activists—reformers and repealers alike—used the phrase “abortion on demand” to signal the latter position.

At a moment when abortion laws, at their most permissive, allowed the procedure to save the life of the mother, reformers viewed themselves as political realists. While some reformers privately supported elective abortion, they believed the stigma surrounding the procedure meant that they could only ask for limited changes from state legislatures. Reform leaders like Dr. Alan Guttmacher maintained that the United States was “not ready” for the “abortion on demand” policies that existed in “iron curtain countries” because it would lead to an “ethical uproar.”

(Image source: Abortion On Demand)

What was often left unstated by reformers–because it was taken for granted–was that the ethical uproar had to do with distrusting women to control their reproduction. You can see the mistrust made explicit in a 1967 article by Dr. Eugene M. Diamond, a Catholic anti-abortion physician. Diamond declared that those “who propose abortion on demand” have “an inordinate confidence in the wisdom of the average woman’s decision to terminate her pregnancy.” A number of reformers shared similar views about women’s capacity to make reproductive choices. Others strategically sought to appease chauvinistic politicians, physicians, and a wider public by proposing policies that mandated male medical and legal authorities deciding which women deserved abortion.

Abortion reformers presented this patronizing position as a reasonable compromise between absolute abortion prohibition and outright repeal. The tactic had broad appeal with politicians and with voters. As much was apparent in Washington State, which saw a successful referendum campaign for abortion reform take place in November 1970. There, the abortion rights campaign emphasized that their program was “not abortion on demand” and underscored that “the medical profession [would] deal responsibly with women in crisis.” At a moment when 92% of physicians in the country were male, reformers made abortion reform palatable by maintaining “responsible” male medical authority. The implication was that these physicians would ensure that women’s access to abortion would remain limited to the deserving few.

This emphasis by reformers on continued male medical authority over women’s reproductive lives was also attractive to the very Protestant denominations that would later join the anti-abortion religious coalition after Roe. In the early 1970s, the National Association of Evangelicals, the Southern Baptist Convention, and Seventh Day Adventists, among others, repudiated “abortion on demand” while accepting “therapeutic abortion based on approved medical indications.” So long as male medical authority over women’s reproduction was intact, these groups officially supported abortion reform. This paternalistic view of abortion would, within a few short years, also form the common ground between conservative Protestants and anti-choice Catholics.

If the paternalism of anti-abortion advocates and abortion reformers was axiomatic, the feminism of repealers was overt. Early proponents of repeal (a coterie of male doctors, lawyers, and mainline Protestant and Jewish religious leaders) insisted that abortion on demand was urgently necessary to “free women from a now needless form of slavery and let her become the master of her own body.” Some, like Episcopal Bishop James Pike, argued that “the right to decide must rest not with a doctor, or a judge, or any third party, but with the mother herself.” By 1967, with the flourishing of both liberal and radical feminism, the links between women’s emancipation and reproductive freedom became ever more apparent.

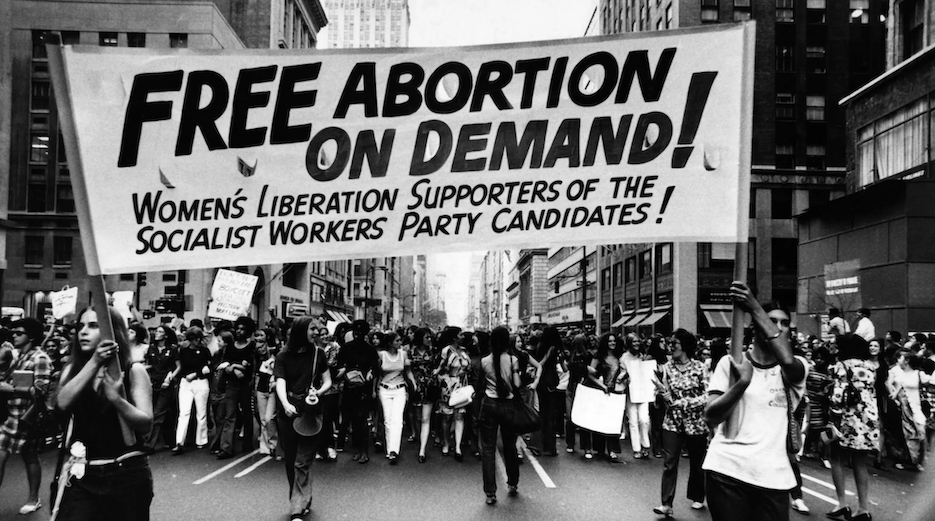

As women moved to the front lines of the abortion repeal movement, they made clear that abortion reform, in the words of Betty Friedan, was “something dreamed up by men” to keep women as “passive objects that must somehow be regulated.” These feminist ideas became highly visible, both in press coverage and in street protests. For example, in August 1970, over 30,000 women marched down 5th Avenue in New York City to commemorate the 50th anniversary of suffrage. This event, named the Women’s Strike for Equality, saw marchers carrying placards calling for “abortion on demand” alongside free daycare and equal opportunities in jobs and education.

Even as reformers and repealers debated how to transform abortion restrictions, opponents of abortion maintained that reform was a slippery slope to repeal. The Catholic Church dominated the early anti-abortion movement. Bishops and budding right-to-life groups in the United States with names like “Voice of the Unborn” linked abortion on demand with mass murder and a moral horror equivalent to the Holocaust. The phrase abortion on demand was still novel enough in the late 1960s that it sometimes warranted qualifying phrases like “so-called,” in the Catholic press. The denigration of “abortion on demand” by these opponents was helped along by the sexism of reformers and a history of press coverage that associated elective abortion with communist countries.

This Catholic-led attack on abortion rights grew louder and more organized from the early 1960s onward in response to the mounting successes of the abortion rights movement—both reform and repeal—in over a dozen states. Most states with reformed laws saw modest increases in abortion access. In contrast, the few states that repealed their abortion laws saw abortion access grow dramatically. In the eyes of Catholic anti-abortion crusaders, abortion access was no longer hypothetical nor confined to abstract policy debates. It was an expanding political and medical reality in the United States and abroad.

For politicians like Richard Nixon seeking to attract socially conservative Catholic voters away from the Democratic Party, the repudiation of abortion on demand would be instrumental in building a new right-wing interfaith coalition within the shell of a desiccated Republican Party.

Nixon’s 1972 campaign was novel, not just in the scope of its criminality, but because it hitched Republican politics to anti-abortion politics, profoundly changing the political landscape. President Nixon commenced his abbreviated second term on January 20, 1973, two days before the Supreme Court issued its ruling on Roe v Wade and Doe v Bolton. In these decisions, the court codified many of the policy demands of the repeal movement and bounded them within a trimester framework. The triumph of repeal and the demise of reform placed reproductive choice in the hands of women and made abortion far more accessible, affordable, and frequent.

Though he campaigned adamantly against abortion to garner Catholic votes, Nixon had a myriad of other issues to contend with once in office, not the least of which was his impeachment. The anti-abortion movement, however, did not lose its focus. Instead, it rapidly adjusted to its new role, shifting from defenders of a restrictive status quo to vociferous opponents of radically expanded abortion access.

It is difficult to overstate the extent to which anti-feminism and misogyny mobilized the post-Roe anti-abortion movement. Roe and Doe repudiated the abortion reform movement and fragmented the interfaith and politically diverse coalition it had built.

The victory of abortion repeal through Roe and Doe was a major catalyst in driving conservative Protestants into the heretofore Catholic-dominated anti-abortion movement. Religious constituencies that had previously accepted abortion (so long as it was controlled by men and rarely granted to women) became unmoored from the abortion rights coalition. Abortion, for them, came to take on the very meanings Catholic abortion opponents had long proclaimed: mass murder, moral chaos, and the upending of gender roles. It is no coincidence that a major site of interfaith contact and religious cross-pollination during the 1970s was the anti-Equal Rights Amendment movement. Led by the devout Catholic Phyllis Schlafly, her vast organization became an interfaith melting pot for anti-feminist and anti-choice politics.

In the ensuing decades, with the rise of an ecumenical religious right and their family values politics, these negative associations of abortion on demand with the destruction of divinely ordained gender hierarchies would become articles of faith. And they would fuel Republican policies and politics for over a half-century.

Meanwhile, by bandying phrases like “safe, legal, and rare,” some Democratic politicians would, in the spirit of the reform movement, attempt to triangulate a rhetorical space between reproductive freedom and outright abortion bans.

Which brings us back to Joe Biden and his invocation of “abortion on demand.” Today, the meanings of “abortion on demand” are again unsettled because the laws themselves are in dramatic flux. Abortion remains legal and accessible in some states. A number of states now have total bans, 6-week bans, or 15-week bans. Some of these restrictive states only allow abortion to save the mother’s life. Others have 1960s-reform-like laws that permit abortions to preserve maternal health or because of non-viable fetuses. A few restrictive states allow for abortions in cases of rape or incest. Even with these chary allowances, women reckoning with tragic personal or medical circumstances have found it difficult if not impossible to get abortions locally.

Dobbs might have been the end of Roe. But it has not been the end of the fight for abortion rights or for women’s social equality. As in the past, competing visions over who deserves reproductive rights are now in play among abortion rights advocates. When the President disavowed abortion on demand, he invoked a historical debate within the abortion rights movement over who deserves abortion access and whether women can be trusted to decide their reproductive futures. That these policy debates are still playing out against the backdrop of a religious movement that would ban abortion points to the fact that women’s reproductive freedom is once again caught between tepid friends and declared enemies.

Gillian Frank is a historian of religion and sexuality who co-hosts the podcast Sexing History. His book, A Sacred Choice: Liberal Religion and the Struggle for Abortion Before Roe v Wade, is forthcoming with University of North Carolina Press.