On Cults, Yellowjackets, and Rewatching Shows

The biblical and religious motifs in "Yellowjackets" and the rituals of rewatching TV shows

(Poster for Yellowjackets)

In Showtime’s hit horror-drama series Yellowjackets, a girls’ high school soccer team (the “Yellowjackets”) from New Jersey experiences a plane crash on the way to their 1996 national championship game. Survivors are forced to scavenge in their crash location—somewhere in the forests of Ontario—which they eventually deify and name “The Wilderness.” As months go by without rescue, the girls engage in ritualized cannibalism for survival. Meanwhile, in the show’s 2021 present, viewers learn that a handful of the Yellowjackets were rescued, but that they have remained silent about their survival strategies.

Readers of The Revealer know this. In September 2022, Valerie Stoker published an essay for The Revealer titled, “On Religion and Modern Life in Yellowjackets and Severance.” As she offers synopses of each show, she unpacks how both deploy religion to explore themes of suffering, violence, and bewilderment. Regarding Yellowjackets specifically, Stoker contends that the team “repeat[s] old patterns” of tribalism for survival—they erect shrines, project their feelings onto the gods, and develop a religion of reciprocity between them and their most proximate deity, The Wilderness. Even for the presumed atheists (e.g., the character Natalie), religion remains imprinted upon the human psyche.

I’ve thought a lot about Stoker’s ideas of repetition in light of the writers’ and actors’ strikes. With fewer new releases, many of us have found ourselves repeating old patterns of viewership and rewatching old episodes of favorite shows. Some thinkers have suggested that there could be psychological benefit to doing this. When experiencing cognitive overload, viewers can rely on the shows they love—and know—without adding to their psychic plates. “Watching something new inherently involves thinking,” says Jennifer V. Fayard, “but there’s no guesswork, cliffhangers, or stressful anticipation when watching an old favorite.”

The show I rewatched the most during the joint strikes is Yellowjackets. My reason for rewatching it, however, was the opposite of generating psychic calm. Rather than taking comfort in what I knew, I wanted to see what I didn’t know—what I had missed or misunderstood. I had hoped that if I rewatched carefully, I could better understand what was happening throughout the two seasons. As viewers of the show know, Yellowjackets is a bit of a mystery: we don’t know the full extent of how or why particular teammates survive beyond the forest. We don’t even know how many survive, let alone why. The Wilderness appears and acts as it does. Is there an empirical reason for the river turning red? Is there a logical explanation for why a tree emits heat in the dead of winter? What are all of the carved symbols about? Will everything eventually make sense or is this another Lost?

As a biblical studies scholar, I am trained to acknowledge the work of repetition. Stories within the Bible are told multiple times and repeat themes from non-canonical sources. There are two creation accounts in the Bible. There are two flood narratives. Even Jesus’ life is told in four different ways, and that’s just accounting for the canonized Gospels. Scholars typically describe this multiplicity as a reflection of the human condition; because humans make sense of the world in differing ways, the Bible includes multiple tellings from various points of view. While the biblical authors may have crafted similar stories independently of one another, many did not. Writers instead borrowed from other writers. They looked to other sources and then offered alternative versions—versions that were similar but could still accommodate differing or even changing needs and standards. The author of Matthew’s Gospel, for example, borrowed what he liked from Mark’s Gospel and then added his own perspective. The author of Luke’s Gospel did the same. Scribes copying sources for circulation also made changes as they wrote, even if minimal. For those who wish to venture into a more robust alteration of Jesus’ life, I suggest reading the non-canonical Infancy Gospel of Thomas. Trust me.

Rewatching a television series is not the same as rewriting a text, at least not literally. The act of rewatching, however, is likely to conjure new ideas within viewers, the kind that could spark further interpretations and revised retellings. What follows then is an experiment in interpretive replication—a rare duplicate within The Revealer. Like the Bible’s second creation account or Matthew’s response to Mark, my investigation of Yellowjackets shares commonalities with Stoker’s review (e.g., noting the show’s focus on ritual, cults, and trauma) but also follows altered treads. I focus in particular on the power of “the repeat,” not just within the show but also within our own rewatchings. I also emphasize the show’s second season, which was not yet released when Stoker wrote her piece. This essay also continues to engage the Bible because, well, it’s what I do. At the risk of burying the lede, my overall contention is this: retelling our stories with room for change and further thinking is one of the best things we can do for ourselves to process suffering and to cultivate care.

***

Apropos my argument, I’ll start with a repeat: in Showtime’s hit horror-drama series Yellowjackets, survivors of a 1996 plane crash are forced to scavenge in their crash location, “The Wilderness.” A handful are eventually rescued but remain silent about their survival strategies for decades.

In both the 1996 and 2021 timelines, the trauma of the crash, starvation, and subsequent survival methods alter the structure of the characters’ psyches. Team members who live beyond the forest have, to varying degrees, post-trauma effects of hypervigilance, flashbacks, nightmares, and dissociations. Their experiences of starvation and suffering resist coherent narrativization, another common effect of trauma, and are often expressed in the 2021 timeline through post-trauma reenactments such as skinning a backyard squirrel (Shauna), beheading the family dog (Taissa), or operating a stuck-in-the-past, 1990s themed video store (Van). Repeatedly, the survivors simultaneously display and recreate their traumas.

In addition to trauma, another term evoked regularly by viewers when considering what takes place in The Wilderness is “cult.” A contested term, cult is commonly understood in popular culture as some form of dangerous, evil, mind-manipulating movement (e.g., Heaven’s Gate, Peoples Temple, NXIVM). Scholars of religion are often quick to deconstruct this definition. Deriving from the Latin cultus, “cult” more broadly refers to the act of “cultivating” care, often through the honoring of gods, leaders, and/or ideologies through ritual and rite. This latter definition leaves room for a wide variety of practices, from Christian worship to SoulCycle classes to NFL team fandoms. It also leaves room to consider more earnestly if, when, and how one chooses to describe a cult as dangerous, evil, and/or mind-manipulating.

Repetition is part of this. Recurring rituals are often implemented in cultic spaces to instill a sense of community, meaning, and focus in an otherwise disordered reality. Replication gives us a sense of control. It helps us connect with those around us. And it helps us manage our emotions. When repetition is bound up in trauma, however, it can be difficult to know when it is healing and when it is a harmful product of a psychic split (e.g., ritualized magical ideation).

In the face of the writers’ and actors’ strikes, I didn’t just rewatch Yellowjackets. I rewatched it. And while I don’t think trauma was fueling this choice, ritualistic behavior and the construction of ceremony did ensue. My general routine was this: meet spouse at scheduled viewing time (community), make sure our dogs are too tired to interrupt (sanctuary), pour our glasses of wine (sanctification), light incense (centering), have the remote in hand (so as to rewind and rewatch again when necessary), and be ready to text others if we encountered something new. If someone hadn’t seen Yellowjackets, we reminded them that they needed to, and if someone hadn’t rewatched it, we reminded them that they should. At one point, we even asked friends to help us cast each of our dogs as a Yellowjackets character. Clearly, we became fanatics. Or missionaries. Or both. Were we on our way to creating a cult? Maybe. Probably not a “cool” one, but definitely something.

(By majority vote: Toby is Misty.)

Regardless of how one morally describes the rituals within Yellowjackets, the team does develop a cult by the “cultivating care” definition. At first, the group leader is team-member Lottie, who guides the Yellowjackets through meditative breath work in an attempt to be in touch with the soul of The Wilderness. With teammate Misty’s intervention, however, the group turns into not just a Wilderness-Listening cluster but a Wilderness-Fearing one. Whereas the Yellowjackets once drew playing cards to reveal what chores would be done by whom, they later turn to the cards to see who will be cannibalized for the others’ survival. The team rationalizes this by maintaining that the hunted, killed, and eaten function as offerings to The Wilderness. In the teens’ minds, it is The Wilderness which chooses who draws the death card; “it chooses” and “it chose” become their common recitations. Eventually, team members adorn masks not only to hide their shame and instill fear in the hunted, but to resemble—become?—their surrounding master (a.k.a. The Wilderness). The hunters’ hunger is also understood as mirroring the hunger of The Wilderness. “It’s not evil. Just hungry. Like us,” Lottie retorts. When a life is given—and eaten—The Wilderness is pleased.

(Yellowjackets during a cannibalistic ritual in The Wilderness)

The more I (re)watched, the more I reflected on how the cult of the biblical God is not so different. Biblical theologies often reflect their authors’ convictions about what their God wants or desires. Trauma is part of this. While, at least from a scholarly perspective, there is no such thing as “one Bible” or “one biblical God” or “one biblical storyline”—multiple authors with differing ideologies wrote the stories within the Bible over hundreds of years (also likely with no foresight that their stories would become canonized)—there are shared themes that help tie the narratives together. One is the human tendency to sense-make in a nonsensical world.

Some of the earliest biblical narratives, for example, blame Israelite suffering on the failure of the collective Israelite self to appease the Israelite God. The book of Hosea’s response to the Assyrian invasion of Israel in the 8th century BCE is a prime illustration of this. According to Hosea, Assyria destroyed the Northern Kingdom of Israel because the Israelites were worshipping multiple gods. In Hosea’s view, external enemies will no longer invade Israelite territory so long as the Israelites take on a henotheistic ideology with the God of Israel at the helm. This kind of self-blame is a common response to trauma. Self-blame implies that the situation is controllable and even reasonable. This makes the world seem less ominous—less chaotic. Offerings become a central part of this. Although not cannibalistic, human sacrifices are ritualistically donated to the God of Israel, including Jephthah’s daughter (Judges 11:30-40), so as to maintain fellowship. So long as the Israelites please their God, their God will please them.

Still, the cult of The Wilderness might appear more daunting. Teens are hunting teens for consumption, using murder as method and Lottie’s calls from The Wilderness as justification for their actions. But the Bible contains horror, too. In Genesis, the Israelite God drowns almost all of the world’s inhabitants. In Exodus, that God hardens Pharaoh’s heart so as to keep the Israelites enslaved in Egypt. In the Gospels, God’s chosen messiah is crucified under the Roman imperial system. And in Revelation, that messiah, now resurrected, burns those who disagree with him for all eternity. Often labeled “texts of terror” by biblical scholars, the Bible is filled with stories of justified abuse, torture, and annihilation.

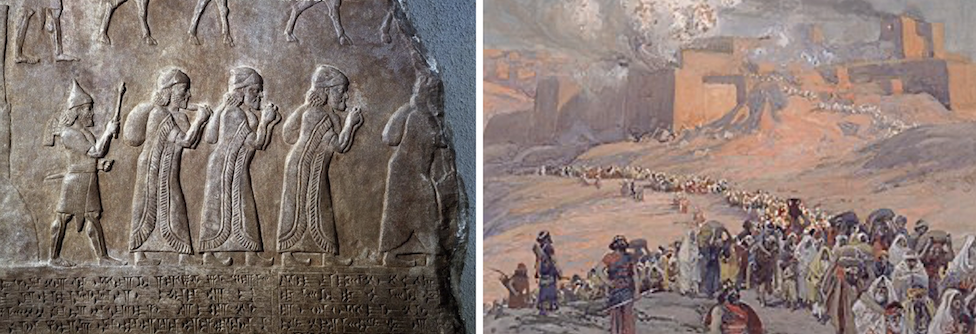

While much of these terrors lack historical reliability, they still reflect the pain and suffering experienced in antiquity. There remains no archaeological evidence, for example, of Israelites enslaved in Egypt or their mass Exodus from Egypt, but there is evidence of repeated violence, oppression, and forced deportation at the hands of non-Israelite nations. The earliest evidence of an Israelite people (ca 1200 BCE), in fact, stems from an Egyptian stele in which Pharaoh Mernephtah boasts of Egypt’s destruction of communal Israel. This historical terror continues. In 722 BCE, the Assyrian empire destroyed the Northern Kingdom of Israel and forced its inhabitants into other Assyrian territories. In 587 BCE, the Babylonian Empire destroyed the Southern Kingdom of Israel, including the Jerusalem Temple, and forced its inhabitants into Babylonia. In 70 CE, the Roman empire destroyed Jerusalem again, and in ca. 130 CE, the emperor Hadrian founded a Roman city on top of Jerusalem’s ruins and forced local Jews into diaspora.

(Left: 8th century BCE relief of Israelite deportees under Assyria. Right: 19th century CE depiction of Israelite deportees to Babylon by James Tissot.)

This history highlights the extent to which biblical tales are crafted as human responses to human suffering—as ways to narrate and make sense of pain, even if (especially if?) the suffering remains nonsensical. While not necessarily drowning physically, the Israelites and later Jews drown metaphorically—over and over again. Like the Yellowjackets, their communal consciousness is under prolonged, life-altering, life-threatening stress. The Bible’s pull to rationalize these traumas is even bound up in further food ritualization: Israelites and later Jews not only offer sacrifices to their God, but also commemorate their connection to that God through ritualized feast: “Eat the meat roasted over the fire, along with bitter herbs, and bread made without yeast…It is the Lord’s Passover” (see Exodus 12:3-14). To this the New Testament Gospels reply: eat Jesus.

(Left: A scene with the characters in Yellowjackets holding a banquet. Right: 16th c. depiction of Jesus’ final banquet by Joan de Joanes)

More than ritual, however, trauma recovery focuses on stories. Because trauma creates fragments within the self—ones that show themselves through manifestations of psychic disconnect (e.g., hypervigilance, anxiety, flashbacks)—recovery requires building new connections. By naming and giving words to traumatic and posttraumatic experiences, storytelling becomes an act of trauma processing—an act that seeks to make sense of and survive its haunting associations and dissociations. This takes time. Single narrations are rarely enough. We must let suffering speak, as Cornell West so aptly heeds. And then we must let it speak again. This is a process, to be sure, filled with reckoning, revision, challenging, and reality-checking. Engaging revision, asserts Brené Brown, is how we “transfor[m] who we are.”

The Bible does this; its many authors process pain through tellings and retellings of traumatic pasts. While the book of Exodus might offer one telling and understanding of the Babylonian exile and experiences in diaspora, Daniel offers another. And Esther another one still. Again, this is not easy. In many instances, the psychic impact of trauma reveals itself in and through the narrativizing process. In Ezekiel, for example, a text that also responds to the Babylonian exile, Ezekiel plays out his suffering through anxious ritualized eating. His pain in exile becomes so disconnected from its source that it attaches onto his eating habits. Not wanting to lose connection with his deity, Ezekiel imagines his limited food intake—a limitation likely caused by the realities of exile in addition to the pain of it—as deserved (self-blame) and wanted by his God. At one point, he even thinks his God is the one choosing what he can and cannot eat, when he can eat, and where. Food within the Bible is thus not just about honoring the Israelite God or commemorating a God-human relationship; it is also about grappling with posttraumatic anxiety and the fact that bad things still happen under that God’s jurisdiction. It is about a people attempting to rationalize their suffering while also yearning for their God to love them.

Yellowjackets similarly immerses viewers into the traumas of its characters. We see them experience a plane crash, death, more death, starvation, hallucination, and the destabilization of their mental capacities. Even more than Ezekiel, viewers are set up to feel for the characters—to identify with them—as the episodes progress. By the time the Yellowjackets eat their second victim and call on Lottie’s connection to The Wilderness for justification, some of us might identify with their justification too. Through the processes of introjection and association, we sympathize with their attempts to survive. We understand their limited capacity to reason under these conditions. And we also understand, as psychotherapist Glenn Patrick Doyle writes on trauma, that “[w]hen we are in pain, we will do almost anything to get out of pain. We will believe anything—or anyone—who seems to have answers.” In the case of Ezekiel, this includes the idea that God wants Ezekiel to suffer. In Yellowjackets, it includes the belief that The Wilderness chooses who suffers. “How else,” as Lottie puts it, “do we explain what happened out there?”

By the time a group of surviving Yellowjackets gather in the storyline’s present—seemingly the first instance of such a gathering since their teen years—viewers want them to reconnect the parts of themselves that remain ruptured. They want the survivors to cultivate care for themselves—to speak, finally, about what happened to them, and to then speak it again. Some survivors try, and in doing so repeat old patterns, showcasing all the more their need to try and try again to integrate their pain into their conscious selves: Lottie hallucinates. Van falls prey to magical ideation. In fact, Van goes as far as wanting a Wilderness repeat; she seems to think an offering to the forest will cure her cancer. During one of our rewatching ceremonies, my spouse declared it stunning that none of the characters, as far as we know, had developed an eating disorder. Perhaps in Season 3 we will learn of another survivor who, like the biblical Ezekiel, imagines The Wilderness choosing what she can and cannot eat, not just in the past, but in her posttraumatic present.

The Wilderness, of course, does not choose by itself. There is a dyadic charge between the Yellowjackets and The Wilderness. The Wilderness may choose for the team, but the team also hunts—and eats—for The Wilderness. It is hard to know when one becomes the other. Perhaps they always were the same. Viewers see the clearest evocation of this dyad in one of the final scenes of Yellowjackets’ second season. “You know there’s no ‘It,’” adult survivor Shauna says in alluding to The Wilderness. “It was just Us.” To which adult Lottie responds: “Is there a difference?”

The Bible is also human-constructed with the depths of the human condition expressed within it. And like Yellowjackets’ Wilderness, neither the Bible nor the God within it speaks for itself. The Bible is made and remade by its interpreters, often through the motivations and projections those interpreters put onto it. “The Bible Says,” for example, can be a weaponizing phrase, reducing biblical stories to a biased monolith. Many of us are familiar with these claims, the ones that benefit the ideologies of the interpreter at the expense of others: “The Bible Says” gays are damned to hell (it doesn’t). “The Bible Says” women must be subservient to men (it kind of does, but it also heavily implies the opposite by glorifying women chopping off men’s heads). Thus even the idea that the Bible “is” anything stems from interpretive bias; “it is rooted in Protestant faith claims around sola scriptura, the theological idea that the Bible is the full revelation of God and needs no intermediary tradition that impacts its meaning or interpretation.” What the Bible “says,” in other words, is as much a reflection of its interpreters as it is of ancient traumas and subsequent human retellings and responses.

In its multiplicity of meaning, exacerbated by both internal and external re-examinings and recapturings of narrative, the Bible, akin to Yellowjackets, reveals human hungers: Hunger for reason. Hunger for processing. Hunger for a provider that, even in its own terror, will not forget its people. But the Bible and Yellowjackets also warn us of the dangers of limited interpretive possibilities. Relying on the singular “The Bible Says” might indeed be parallel to “The Wilderness chose.” Both are reductionist. And both mask the reality that the Bible and The Wilderness are human-made. Perhaps, then, expanding our limits—rinsing, repeating, and retelling our stories while being open to additional or even counter information or explanation—is one of the best things we can do for ourselves. This is not just about trauma narration or the need to speak pain and then speak it again. It is also about looking back on where we’ve been, what we’ve seen, and how we’ve coped with an openness to do and see things differently. I understand that this may seem like a simple conclusion. Our post-2016 political moment, however—one that will require many tellings and retellings in order to process—reveals just how much this thesis is in need of saying and saying again.

This to me is cultivating care, which is oddly enough what I got from ceremonially rewatching Yellowjackets during the writers’ and actors’ strikes. I do hope, however, that if someone else were to watch and rewatch the show, they could figure out why the river turns red, why the tree is so hot in winter, and what in The Wilderness’ name is up with that symbol.

Sarah Emanuel is Assistant Professor of Theological Studies at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, CA. Her area of research includes biblical studies and its relations to trauma. She lives on the coast with her wife, pets, and espresso machine.