Dreaming of a Jewish Christmas

The beloved Christmas music created and performed by American Jews

(Image by Getty Images)

My favorite Christmas jingle was written and performed (loosely speaking) by my daughter. Like most kids, she loved Christmas, since it was the season when her grandparents tried to see if they could literally bury her in gifts. At least a couple of those gifts, putatively, came from Santa.

As a longstanding Jewish person, I never believed in Santa—my parents explained early on to my brother and me that my peers were all duped by a coordinated campaign of jolly bearded duplicity and warned us not to disabuse them. We were dutiful, and kept the secret, as far as I remember. We might have felt a little superior about it, which seems forgivable, since we were five and six at the time.

My family was never particularly religious, and I’ve only gotten more secular and assimilated over time. So I was happy enough for my non-Jewish wife’s parents to disgorge great gouts of Christmas presents rather than great gouts of Hanukkah presents; the small child was ecstatic either way.

Still, 5000 years of history is hard to toss out entirely, and I have to admit I was a little leery about lying to my daughter in order to advance the Christmas rituals, however jolly.

So I didn’t lie. I told my 4-year-old daughter, “Santa Claus isn’t real.”

And she got a big smile on her face and said in a sing song, “Yes he is! I don’t believvvvee you!” Then she dissolved into giggles.

Which put me in my place, I guess.

My daughter didn’t know it at the time, but her little foray into Christmas singing had a great deal of Jewish precedent. Jews have written and performed much of the contemporary Christmas music canon.

Christmas is in many ways central to American identity, and Jewish Christmas songs have (like my daughter) claimed that American identity for Jewish people, helping Jews fit into America. Jewish songs can also (like me) express distance or ambivalence about the season and its meaning. The Jewish Christmas music tradition is both about belonging and not belonging, about belieevvvveing and not believing. If America is a winter wonderland, that winter wonderland has, in part, been built by Jewish people. Though sometimes we maybe still shiver a bit.

The Mixed Meaning of Christmas for Jewish Immigrants

Jewish immigrants to the United States had very different experiences with Christmas in their countries of origin. As Joshua Eli Plaut explains in his 2012 monograph A Kosher Christmas: ‘Tis the Season to Be Jewish, German Jews in the nineteenth century were well-assimilated and often had Christmas trees in their homes. Theodor Herzl, for example, generally viewed as the father of the Zionist movement, had a Christmas tree at his house in Vienna. A rabbi expressed dismay at Herzl’s adoption of the Christmas custom, but Herzl wrote in his diary, “I will not let myself be pressured! But I don’t mind if they call it the Hanukah tree—or the winter solstice.”

Christmas had a rather dissimilar meaning for Jews in Eastern Europe. Pastors there on Christmas preached antisemitic sermons blaming Jews for the death of Jesus, frequently inciting violence and pogroms. In Warsaw in 1881, a stampede in a church on Christmas day killed dozens. The public blamed Jews, sparking a three-day riot in which numerous Jewish women were raped, two Jews were murdered, 24 were hospitalized, and more than a thousand Jewish homes and businesses were destroyed.

Immigrants brought these varied experiences of Christmas to America with them. Jewish children and parents were attracted to the Santas and the presents and the trees. But as Christmas became institutionalized as an American tradition (it was declared a federal holiday in 1870), American Jews could also feel alienated or excluded. Jewish Christmas music became a way to express both attitudes—Jewish Christmas enthusiasm and Jewish Christmas skepticism.

White Christmas For All

Jewish Americans weren’t the first to create a secular Christmas tradition. Clement Clark Moore’s famous 1823 poem “Twas the Night Before Christmas” and cartoonist Thomas Nast’s famous drawings of the rotund, jolly Christmas icon helped Santa displace Jesus as the holiday’s most familiar image by the end of the 19th century.

But while they didn’t initiate the trend towards secularization, Jewish songwriters and performers eagerly embraced it. Benny Goodman, the child of Polish Jewish immigrants and a popular bandleader, recorded “Jingle Bells” in 1935 with an all-star band including (non-Jewish) trumpeter Bunny Berigan and (non-Jewish) drummer Gene Krupa. Singer Mel Tormé wrote “The Christmas Song” in 1945 in the middle of a sweltering summer in an effort to beat the heat—a song about a frigid Christian holiday written during a heat wave by a Jewish composer.

“Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!” and “Do You Hear What I Hear?” were also created by Jewish writers. Probably the most critically acclaimed Christmas album of all time, 1963’s A Christmas Gift for You From Phil Spector, was masterminded, like the title says, by Spector, who was Jewish. Of the ten best-selling Christmas albums of all time, at least two—Barbra Streisand’s 1967 A Christmas Album and Kenny G’s 1994 Miracles—are by Jewish artists.

The most famous and influential Jewish Christmas song is undoubtedly Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas.” Berlin’s wife was Christian, and they celebrated Christmas at home, according to Plaut’s A Kosher Christmas. In fact, Berlin’s three-week-old child died on Christmas day in 1928; he and his wife visited the baby’s grave on the holiday most years.

Berlin wrote the song, however, in 1941, when he was working in Hollywood and couldn’t make it home to the East Coast. The song’s dreamy wistfulness (“I’m dreaming of a white Christmas/just like the ones I used to know/Where the treetops glisten and children listen/To hear sleigh bells in the snow”) is about missing family, living and dead. It’s a vision of a de-Christianized heaven.

That heaven is particularly American. Berlin’s biggest previous hit was the patriotic “God Bless America.” Berlin thought, presciently, that “White Christmas” would be even more successful.

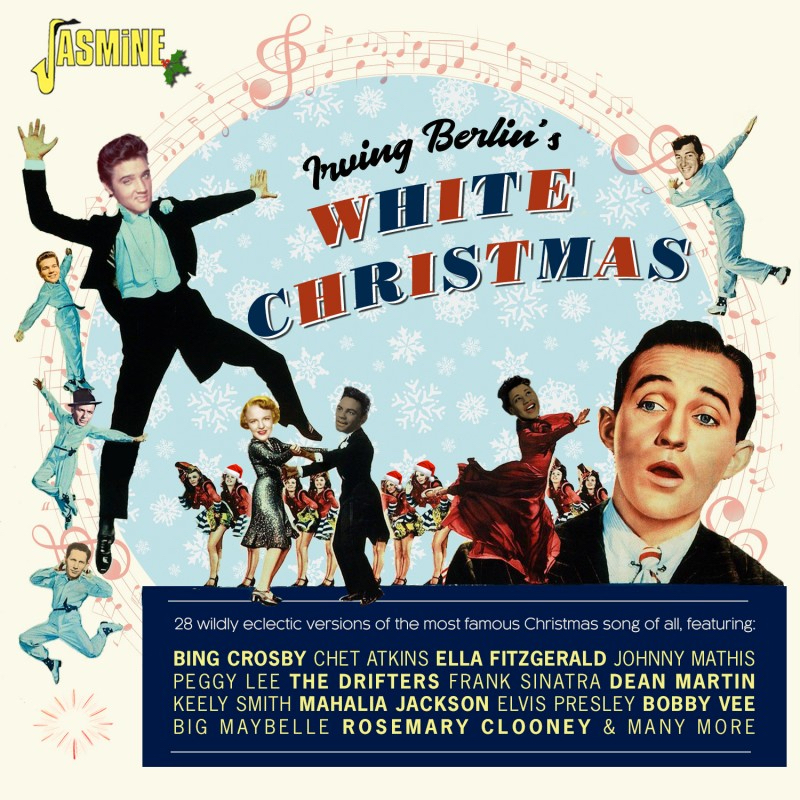

(Cover image of an Irving Berlin White Christmas album)

The song first aired during the Kraft Music Hall radio show, sung by Bing Crosby just weeks after Pearl Harbor. U.S. soldiers preparing to travel to Europe or the Pacific embraced the lyrics for their vision of an idealized home front, covered in gentle gleaming drifts of peace and goodwill. Crosby was hesitant about performing “White Christmas” for the troops overseas because it “invariably…caused such a nostalgic yearning among the men.” But whenever he tried to cut it from the setlist, the audience rebelled. “These guys just hollered for it,” he said.

Turning Christmas from a religious festival into a celebration of sentimental American values—home, family, public fellowship—made the holiday more inclusive and more accessible to Jews. As Philip Roth wrote, “If supplanting Jesus Christ with snow can enable my people to cozy up to Christmas, then let it snow, let it snow, let it snow.”

But cementing American identity with white Christmas snow also had potential downsides. That ambiguity is difficult to miss in what I’d argue is the greatest version of “White Christmas” — the 1956 performance by the African-American vocal group The Drifters. The lead on the record alternates between bass-baritone Bill Pinkney and the dramatic high tenor of Clyde McPhatter. The song’s swing is infectiously bright, defying the melancholy of the lyrics. But at the close, the pace slows and the music drops out. It’s just Pinkney, a Black man singing in an era of Civil Rights demonstrations, caressing the words, “May all your Christmases be whiiiitttte.”

The Drifters’ cover underscores that while Berlin had secularized American identity, he hadn’t integrated it. “White Christmas” is a song that welcomes Jewish people into Christian whiteness by deemphasizing the Christology and emphasizing the whiteness. That leaves out people like the Drifters. But it leaves a question mark on white Jews as well, who aren’t always considered white everywhere. When the Drifters sing “White Christmas,” it’s about the distance between America’s vision of universal brotherhood and the reality of segregation, racism, and violence. That’s not what Berlin intended. But it’s in the song nonetheless.

Rudolph vs. Christmas

You can hear mixed emotions in other Jewish Christmas songs as well—most notably in that other massive Christmas classic, “Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer,” by Jewish brothers-in-law Robert L. May and Johnny Marks. Rudolph, per the famous lyrics, has a “very shiny nose,” which makes him a pariah among his fellow ungulates.

All of the other reindeer

Used to laugh and call him names

They never let poor Rudolph

Join in any reindeer games.

Then one foggy Christmas Eve

Santa came to say

“Rudolph, with your nose so bright

Won’t you guide my sleigh tonight?”

Then how the reindeer loved him

As they shouted out with glee

“Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer

You’ll go down in history”

Many critics over the years have pointed out that “Rudolph” is a disturbing story. The titular reindeer’s peers mock and bully him because his nose is red and glowing. It’s only when it turns out that his nose can provide light for Santa’s sleigh that the other reindeers accept him. Michael Schaffer at The New Republic argues that the song presents “a dystopia where affection is based on economic worth.”

May, the lyricist, said the song was partly based on his own experiences of childhood, when he was “shy” and “small.” He added that he “had known what it was like to be an underdog.” The song was also written while his wife was in the middle of a long illness that eventually led to her death. May described being “relieved” when Christmas decorations were taken down; thanks to his wife’s illness he “didn’t feel very festive.”

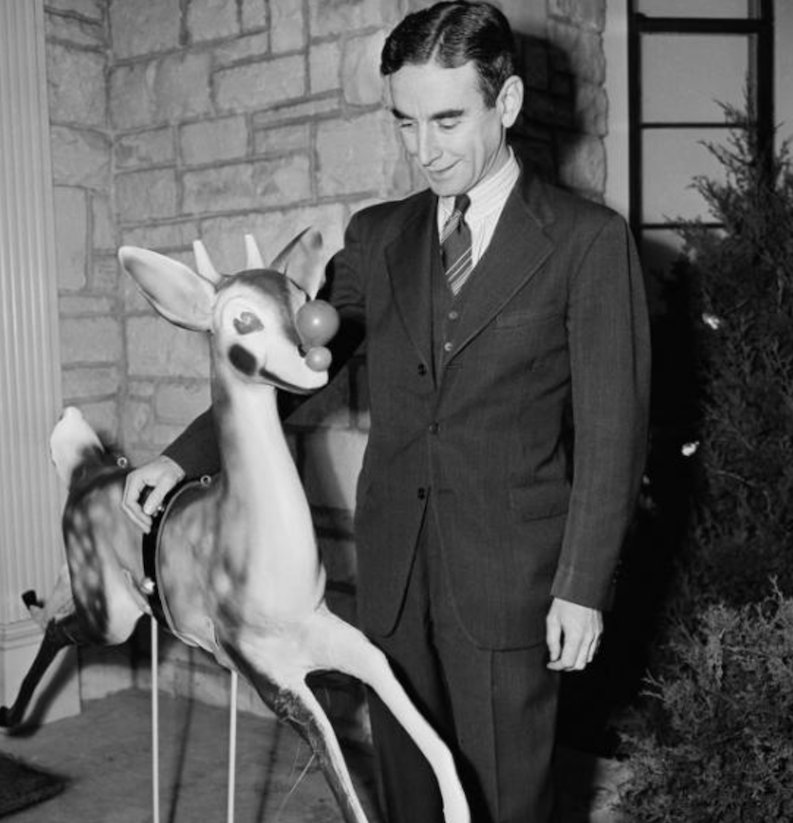

(Robert L. May with Rudolph. Image credit: 18 Doors)

These details of ostracism and alienation are personal; they’re from May’s life story. But they have a wider Jewish resonance. Many Jewish American children, after all, at various times in various places have felt left out during the holiday season.

On the surface there’s a happy message of inclusion, since Rudolph is ultimately welcomed into Christmas fellowship. But in order to be accepted, he first has to be more valuable and better at Christmas than his peers. Donner and Blitzen don’t have to win Santa’s regard through service; they start out beloved. Rudolph has to work at it and prove himself a valuable asset, as Jewish people have often had to prove that they belong, especially at Christmas. Part of the joke in Jewmongous’ acerbic, Christmas-bashing “Reuben the Hook-Nosed Reindeer” is that the song isn’t exactly a parody. It’s just acknowledging Rudolph’s original Jewish subtext.

If “Rudolph” can be heard as an ambivalent acknowledgement of Jewish exclusion at Christmas and “Reuben” as outright Jewish mockery of the holiday, Simon and Garfunkel’s lovely “Silent Night/7 O’Clock News” is somewhere in the middle—functioning as both an expression of nostalgic disappointment in and a critique of Christmas’s promise.

Released in 1966, the track features Jewish singers Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel combining their angelic harmonies on a reverent rendition of the hymn “Silent Night.” At the same time, a simulated news report is read. Over the course of the song, the news rises in volume, drowning out the singing as it details a variety of grim stories of the day—the failure of Civil Rights legislation, the murder of student nurses by Richard Speck, the ongoing war in Vietnam.

The song is an ironic comment on America’s failure to live up to the values it professes on Christmas—love, good fellowship, peace. Sung by a Jewish duo, though, it could also be a suggestion that Christian values aren’t love, good fellowship, and peace at all. If, traditionally, Christmas for some Jews has been a season of persecution, then “Silent Night” is a fitting complement to news of violence and hate. As with “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” and even “White Christmas,” Jewish Christmas songs often get their power from the fact that they are in some ways also anti-Christmas songs.

Skronking In a Winter Wonderland

Next to my daughter’s semi-musical pledge to Santa, the Jewish musical performance I love the most may be a brief snippet of a Christmas Eve performance by saxophonist John Zorn and friends at the 6th Street Synagogue, available (though not much viewed) on YouTube.

The band, including bassist Shanir Blumenkranz, percussionist Cyro Baptista, and saxophonist Greg Wall, launches into a noisy free jazz version of “Winter Wonderland.” The tune is gloriously mangled and distorted; rather than strolling happily through a peaceful snowy landscape, it fights its ways through storms and murderous blasts of icicles and sleet gremlins. This is a winter with teeth.

You could see the performance as a bunch of (mostly) Jewish musicians in a Jewish venue deliberately desecrating a Christmas chestnut, giving the bland goyish season a skritchy funky New York makeover. But while “Winter Wonderland’s” lyrics were written by a Christian, the music is by Felix Bernard, who was Jewish, as John Zorn (a man obsessed with the unexpected corners of Jewish music) was certainly aware.

In that context, the performance doesn’t feel like mockery, but like an exultant escape. Zorn and company snap those trite lyrics off and pursue the song’s sophisticated swing into the barrage of cosmopolitan mishigas for which, they insist, it was always intended.

Believing in Not Believing

It’s tempting to give Zorn the last word, or skronk, but it’s not very Jewish to be overly triumphant, especially on Christmas. Jewish Christmas music helped create a secular culture that’s more open to Jewish people in some ways. It’s provided a blueprint for resistance, too. But as Khyati Y. Joshi writes in her 2020 book White Christian Privilege, “Christian beliefs, norms, and practices, and indeed, a Christian way of looking at the world, infuse our society, enjoying countless legal, structural, and cultural supports.”

The fact that most people don’t know that “White Christmas” or “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” or “Winter Wonderland” were written by Jewish songwriters suggests that Christmas is still, despite Irving Berlin’s best efforts, a religious, Christian-identified holiday, even if it’s also to some extent a secular one. Religious aspects of Christmas are seen as less and less important to many Americans. But at the same time, the right has tried to shame people into dropping the nondenominational “Happy Holidays” for “Merry Christmas”—a silly controversy which nonetheless seems designed to remind Jews, and all non-Christians, that, at least in the eyes of some, we don’t belong in Christmas, or in the U.S.

Still, whether we belong or not, we’re here. My daughter is 20 now. She no longer believes in Santa, though she likes getting Christmas presents. I enjoyed pretending with her that Christmas was our holiday, and that it wasn’t. And I’m proud that she figured out that Christmas was a time for Jewish people to make up our own songs.

Noah Berlatsky is a freelance writer in Chicago. He writes about culture, politics, music and other subjects at his substack, Everything Is Horrible.