Not So Sorry

It’s a Beef: How Revenge Movies and TV Shows Help Us Cope

Revenge fantasies can help us heal. But do they come with their own dangers?

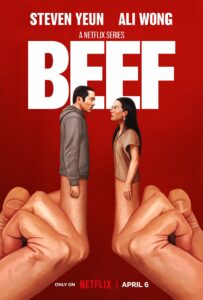

(Illustration of Beef’s main characters. Image source: Netflix)

Driving can be dangerous, and driving can be rage-inducing. When someone cuts you off in traffic, you may allow your imagination to run wild, possibly to violent places. That’s the premise of the new Netflix series Beef, which spirals from a driver honking and giving the finger into an incident of road rage so severe it becomes an operatic tale of revenge.

Beef creator Lee Sung Jin told Forbes that the series was inspired by his own road rage episode, when he started to follow a driver who cursed at him. But Lee quickly changed his mind and drove off, unlike Beef character Danny, played by Stephen Yeun. Danny’s fragile mental health snaps after Ali Wong’s Amy pisses him off in a parking lot, inciting a car chase and bitter fallout, unfolding over ten episodes that depict elaborate and violent paths of revenge that few of us will ever follow.

Beef has sucked in so many viewers because it allows us to live out the fantasy that we can extract justice from our enemies and maybe even get away with it. Like many other revenge stories, Beef has a religious subplot that delves into the complex ties between race and religion in Los Angeles’s Korean Christian communities. If revenge is the opposite of religious teachings about forgiveness, it’s also something we’re culturally and socially discouraged from pursuing. What revenge movies and TV shows do is to provide an outlet for our desire to get even or settle the score with people who’ve done us harm. The longing for revenge is deeply human, but we constantly suppress it so that our lives don’t turn into chaos. Because religion so often focuses on revenge as a moral wrong, revenge stories also give us a guilt-free way to imagine what our own acts of revenge might be like. While we might not escalate our own revenge fantasies to the scale that Beef does, movies and shows that depict someone getting even can provide a socially acceptable way for us to imagine our own acts of revenge.

(A scene from Beef. Source: Netflix)

Psychologists who study revenge fantasies have discovered that children who experience trauma frequently imagine revenge as a way of coping. Because children feel a lack of control over their circumstances, revenge fantasies can help them to regain agency and give them an outlet for their anger and confusion. As adults, revenge fantasies can similarly provide an outlet for people who’ve experienced trauma, particularly for adults dealing with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Because trauma can make us feel humiliated, imagining revenge is a way of protecting ourselves from further harm. Psychologists Craig Hain and Anna Weber argue that visualizing revenge can “regulate feelings of injustice and loss of control,” which in turn can help a person regain stability after a traumatic experience.

On the other hand, the danger of revenge fantasies is that repetitive escapes into them can exacerbate feelings of distress. Researchers who work with people who actually enact revenge have found that they don’t rid themselves of post-traumatic symptoms. Many psychologists argue that revenge fantasies should be contained to an occasional occurrence, guided by a therapist, making them just one pathway a person might briefly travel on their way toward healing. This idea of revenge fantasies as a pathway would also help explain why revenge movies and TV shows are so enjoyable. They allow us to imagine what it would be like to act on our imaginations, but only for a couple of hours at a time, and always with an exit ramp back into a more comfortable reality.

Revenge fantasies have a long history in art and culture, but in the Renaissance they became an obsession for writers and audiences alike. The revenge plays of Shakespeare, Thomas Kyd, and Thomas Middleton, among others, became so popular they turned into an entire theatrical sub-genre of the tragedies audiences greatly enjoyed. The English Renaissance philosopher Francis Bacon’s influential writing on revenge, along with the violent religious conflicts that surged as Protestant kings and queens sought to purge England of Catholics, meant that revenge was much on the minds of theatrical audiences. Bacon described revenge as “a kind of wild justice; which the more man’s nature runs to, the more ought law to weed it out,” and warned that “a man that studieth revenge keeps his own wounds green, which otherwise would heal and do well.” Revenge plays were a way to show audiences how revenge could have catastrophic outcomes, as it does in Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, but they were also bloody, murderous, candlelit fun.

Renaissance revenge tragedies mostly follow a similar structure, one that’s still imitated in revenge movies and TV shows today. A person is driven mad by the murder of someone close to them. They then discover the identity of the murderer, either through a visit by a ghost (in both Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy and Shakespeare’s Hamlet) or via their own sleuthing. In turn, they plot revenge on their enemies, which sometimes escalates to gruesome proportions. This may have peaked in Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, when Titus murders his enemy Lavinia’s sons, bakes their remains into a pie, and serves it to her at a banquet. I once saw a production of Titus where the entire cast pretended to vomit during this scene, but the audience’s groans mixed with fits of uneasy laughter at the over-the-topness of it all showed that hundreds of years later, Shakespeare’s revenge fantasies still resonate.

A cursory scroll through any listicle of revenge films shows that most of these movies still follow a fairly comparable plot pattern to their Renaissance ancestors. Gone Girl, Memento, Gladiator, Old Boy, Promising Young Woman, Midsommar and pretty much the entire Quentin Tarantino catalog follow similar story arcs to Hamlet, The Revenger’s Tragedy, and The Spanish Tragedy. A person is wronged, sets out to correct that wrong, and vengeance is theirs. These movies are often violent to uncomfortable degrees, depending on your tolerance for onscreen violence, but the death and fighting is often cartoonishly epic in scale, with hundreds of extras being mowed down in epically scaled explosions, sword fights, or gun battles.

Many of these movies also have religious themes or subplots, which allows them to offer escapism from moralistic real life. Midsommar is about a death obsessed pagan cult that the grief-stricken protagonist is slowly sucked into. The writer of Promising Young Woman, Emerald Fennel, described the main character as an “avenging angel” and told an interviewer she hoped the film would act like a Biblical parable about revenge. Oldboy director Park Chan-wook grew up Catholic in Korea, where he was aware of “a sense of guilt that is unique to Catholics.” As a film’s depiction of retribution escalates, viewers can use the character’s pursuit of revenge as a substitute for their own with far less dramatic moral consequences.

The John Wick franchise has made revenge into its entire modus operandi. Played by Keanu Reeves, the films’ titular retired assassin is given a puppy by his dying wife in the first film, and when baddies break into his home and kill the puppy, it leads to an escalating series of revenge acts that quickly reach absurdist degrees. The John Wick movies are also loaded with Catholic symbolism, including a pope-like character called “the elder,” adding some religious balance to all the carnage. The formula has proven so popular that there are now four John Wick movies for people to binge if they’re having a particularly bad week.

But that propensity to take revenge to the most outrageously violent endpoint is where many of these films and shows can lose their audiences. Even for people like myself who think and write frequently about social and religious pressures to be forgiving, the excessive scale of revenge depicted in these productions can be overwhelming, the equivalent of being stuck inside a first person shooter video game for hours on end. And that can be fun, but it can also be exhausting.

(Beef poster. Source: Netflix)

I loved streaming Beef, but as it went on, I found myself thinking that I wanted to get through it as quickly as possible. Watching the two main characters decimate their lives and hurt the people around them for the sake of revenge became queasily challenging as things tipped out of control. I lost interest in Tarantino’s movies years ago, depressed by his overuse of racial slurs and casual misogyny, but also because I don’t have the stomach for hours and hours of people being shot and stabbed for the sake of revenge. For some of us, revenge fantasies, as it turns out, have their limits.

How much revenge is too much? Just as psychologists argue that our own revenge fantasies can be a healthy means of coping if we contain them to the world of the imagination and use them to move through a trauma, the same might be said for revenge movies and shows. If there were multiple seasons of Beef, would we really want to watch them back-to-back? I’m sure there are people who’ve had a John Wick weekend, but that might be too much revenge for most people. Some Shakespeare theater companies won’t even touch Titus Andronicus, worried it will turn off audiences looking for escapism via the cozy familiarity of A Midsummer Night’s Dream or Twelfth Night.

The real tragedy is that today, revenge can escalate into horrifying real-world incidents of mass shootings as acts of revenge, something so common that it is difficult to think of a week that has gone by this year without one. In the face of that scale of tragedy, depictions of revenge on screen might seem dangerous or like a form of temptation. However, we already know that violent video games do not, despite arguments to the contrary, have a strong connection to America’s gun violence epidemic. There is some evidence that after the release of a popular, violent video game, violent crime rates go down rather than up, suggesting these games, and perhaps these films and shows, offer people an outlet for revenge fantasies, and are not the source of gun violence in the United States. That’s more the result of unfettered access to guns and an obsessive attachment to the Second Amendment.

Like any media depicting violence, if we consume it with some degree of awareness, revenge movies and shows can be a way of processing our pain so we can avoid acting out a desire for revenge. These productions can theoretically help us avoid tragedy by depicting revenge’s worst possible outcomes. The fact that many of them end with the main characters regretting their revenge isn’t a coincidence. Shakespeare was a deeply religious moralist, and his revenge plays end with a message about the danger of revenge when it goes too far. Beef also ends with a depiction of revenge’s danger, becoming a modern fable for our age. If forgiveness needs to have limits because some things are unforgivable, perhaps we need to put limits around our revenge fantasies too.

Kaya Oakes is the author of five books, most recently including The Defiant Middle: How Women Claim Life’s In Betweens to Remake the World. She teaches writing at the University of California, Berkeley.