Tainted Love: Reckoning with the Damage of Purity Culture

Could conservative Christian teachings about sex cause physiological and psychological problems that last into adulthood?

(Image source: Katarzyna Bogdańska)

Elizabeth* finds dating anxiety-inducing, but nothing compared to her teenage years.

Now in her twenties, Elizabeth says, “I had a boyfriend in high school and I realize now there were situations where I felt uncomfortable and anxious because of what I’d been fed through church teachings.”

“Dating was not celebrated or seen as a good thing,” she says. “It was a thing to be afraid of, because of ‘temptation’, and what might happen. At the time, I thought the anxiety was hormones and everything was normal, asking: ‘Should I be doing this? Am I in the right place? Am I wearing the right thing?’ As an adult I can see it more clearly.”

Today, Elizabeth recalls dissociating during church teachings about sexuality. “I used to think I was ‘zoning out’ at the church youth group when subjects like ‘guarding your heart’ – gatekeeping your sexuality – came up that I found ‘sticky’ or difficult,” she says. “I realize now, that was dissociation.”

For Elizabeth, dissociating when thinking about sex did not end in youth group. “Detaching to protect myself like that,” she says, “has continued into adulthood and dating.”

According to Elizabeth, church leaders pulled young couples aside and delivered strict messages about dating. She recalls that “a lot of people in that setting wouldn’t even use the words ‘virginity’ or ‘sex’. But the message was ‘don’t have sex, stay pure, be a virgin’. That’s it. No discussion.”

Elizabeth saw several relationships crumble under the pressure to stay “pure” and prepare for marriage. “The expectation of getting married and starting a family young was very much ingrained at church, which just isn’t the reality of life,” she says. “Relationships are messy, and things go wrong. Seeing friends break up, and it being messy and distressing for them, showed me that that way of thinking was not healthy.”

“I definitely think there’s a collective trauma experience for people that have come out of purity culture,” Elizabeth insists.

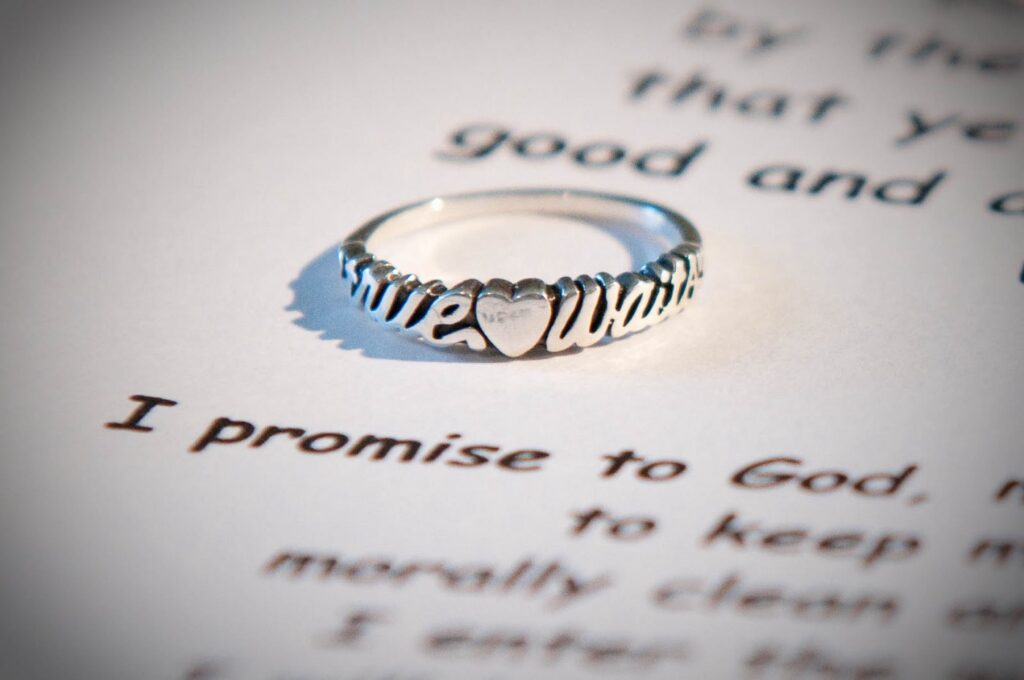

“Purity culture” refers to conservative Christian teachings designed for teenagers that tells them sex outside of marriage is a uniquely bad sin and that, for the sake of their relationship with God and their future spouse, they must abstain from sex until marriage.

(Image source: Religion Media Centre)

Luke Dowding, 34, also grew up in a Christian community that promoted purity culture. He spent years abstaining from sexual relationships as he followed teachings at a Baptist church in the south of England. It was not until his early 20s when he finally broke with church doctrine.

While training for ordination, Luke was asked to sign standards of behavior, including one about sexuality. “There’s a clause in the rules of accreditation in the Baptist life that refers to – and it’s a crass phrase – ‘same-sex genital relations’,” Luke explains.

The rules forbid ministers from not only engaging in LGBTQ relationships, but also from supporting or accepting them. Luke says, “I made the decision that I couldn’t sign that. I wasn’t yet properly out, but I couldn’t sign that bit of paper.”

Religion has long been a significant part of Luke’s life. As a teenager, he met weekly with his Baptist peers, bringing their well-thumbed youth Bibles full of highlights, sticky notes, and underlined passages. Once a year, the youth minister passed around print-outs with stick figures and spoke awkwardly about the importance of abstinence.

“I remember him warning us about giving a significant part of ourselves to someone other than our spouses,” he says. “How you’ll never get it back. If you waste it, then not only are you harming yourself but you’re harming the other person and God.”

Luke says the messages he received about sex were stark. “It was: ‘This is the right way to be, and then the other way is wrong.’ It would be too generous to refer to it as ‘sex education’. It was ‘sex avoidance education’, ‘lust management education’. ‘Instruction’ is a better word. It wasn’t educational or informative.”

“Back then I couldn’t imagine a time I would want to have sex,” he says, “because the teaching was so uncomfortable.”

Luke’s teenage faith was complicated by the fact he is attracted to men.

He says that, “At church, the standard response to a statement like, ‘It doesn’t seem fair that gay people go to hell’, would be: ‘Pray for them, because that’s the consequence of sin.’”

“As a young teenager I would find ways of experimenting with my sexuality, and then go into these almost trance-like episodes afterwards,” he says. “On one occasion I kissed another boy. Afterwards I felt the need to go and wash my mouth. I had almost OCD-like obsessive responses to things: praying, physical cleanliness, and spiritual cleanliness. These were paired with constant mental berating: ‘You’re not good enough, why have you done this? You’ve slipped up again. Why have you let God down? Why have you let your church down?’”

Eventually, Luke suffered from disordered eating and anxiety, for which he sought treatment.

“Having been in therapy I understand the way that I’m wired now, and moments of anxiety that I still experience are rooted in this sense of impurity,” he says. “The need to constantly strive to be better than I am to overcome this impurity, through devotion and acts of service, was instilled in me during those years.”

***

Like Luke and Elizabeth, as a teenager I was taught that “true love waits,” a popular purity culture catch-phrase first coined by Southern Baptists in the 1990s. I distinctly recall a church youth leader who described sexuality as a pie chart, and drew a line down the middle. She said that if you have sex before marriage, you give less of yourself to your spouse (and a part of you permanently belongs to someone else). I also witnessed talks to teenagers at an evangelical conference where a speaker blamed herself for two sexual assaults.

As a former purity devotee, I was curious if Luke and Elizabeth’s assertions that purity culture negatively influenced their mental and physical health were common. And I wanted to know what other former evangelicals have been doing to bring these issues to light, and learn if they have found ways to heal.

Adolescence

“Purity culture” is well-accounted for as a phenomenon (not least by The Revealer), which reached its height in the 1990s and 2000s. Teachings apply to adolescents, but often weigh more heavily on girls because of assumptions that men’s sexual needs are greater, that sex is a wife’s obligation, and that women must gatekeep their sexuality from men. Within communities that promote purity culture, teenagers are encouraged to wear symbolic purity rings until marriage, and girls are encouraged to attend purity balls with their fathers to show their virginal loyalty to their dads until marriage.

In the United States, purity culture drove decisions on sex education in public schools for decades, a decision that proved to fail young Americans. In 2017, a review on the harms caused by this form of sex education in the Journal of Adolescent Health called for “abstinence-only until marriage” programs to be defunded. Several studies in the review showed an association between abstinence education policies and higher rates of teen births and chlamydia infections. Purity pledges, where teenagers sign a commitment to abstain from sex until marriage, were shown to increase clinical risks: as part of the same 2017 review, researchers found higher rates of human papillomavirus and nonmarital pregnancies among teen girls who took a virginity pledge compared with peers who did not.

Adulthood

Risks from purity culture are not limited to teen pregnancy and STIs. In 2021, a study by Sheila Wray Gregoire and colleagues of 20,000 married Christian women, of whom 77.5% were evangelical or formerly evangelical, found that 22.6% reported vaginismus or some other form of primary sexual dysfunction that makes penetration painful. (Prevalence is estimated to be 5-17% in clinical settings). For 6.8% of women surveyed, penetration was so painful it was impossible. Authors presented the study at the American Physiotherapy Convention, are seeking peer review, and have made the data publicly available.

The researchers also conducted one-on-one interviews with women for the book, The Great Sex Rescue. Many participants reported domestic assaults. One said her husband attacked her in the shower on their honeymoon. “We hadn’t had sex before we were married, and I wasn’t ready yet,” she told them. “I remember freaking out in my mind, crying and praying, ‘What is this? I can’t live with this for the rest of my life.’” And yet she didn’t think of it as an assault until she told her divorce lawyer.

The researchers found that 43% of respondents said they had been taught before they married that “a wife is obligated to give her husband sex when he wants it.”

Wray Gregoire, herself a former evangelical, says that, “The ‘obligation’ message given to women regarding sex is highly implicated in vaginismus, as are messages which take away a woman’s agency or bodily autonomy… Other peer reviewed literature has found that religiously conservative women of a variety of faiths have higher rates of dyspareunia [pain during or after sex], and we think this is the root of it.”

Wray Gregoire is not the first to explore how purity culture could contribute to sexual dysfunction and physiological problems. In 2018, Pure, by ex-evangelical author Linda Kay Klein, catapulted the harms of purity culture into U.S. bookstores. The book compiles stories about the mental and physical harms that dogged women after abstinence-only sex education.

Wray Gregoire is not the first to explore how purity culture could contribute to sexual dysfunction and physiological problems. In 2018, Pure, by ex-evangelical author Linda Kay Klein, catapulted the harms of purity culture into U.S. bookstores. The book compiles stories about the mental and physical harms that dogged women after abstinence-only sex education.

Klein’s work is part of an emerging genre of non-fiction led by “purity survivors.” Popular examples include the books You Are Your Own by Jamie Finch (2019), Shameless by Nadia Bolz-Weber (2019), Talking Back to Purity Culture by Rachel Joy Welcher (2020) and Beyond Shame by Matthias Roberts (2020). The documentary Give Me Sex, Jesus (2015) and feature film Yes, God, Yes (2019) also illustrate the pressure teenagers face under purity culture.

Klein says that during the course of writing her book she heard accounts of women whose symptoms “mimicked the symptoms of PTSD,” and faced vaginismus, pelvic pain and primary sexual dysfunction, self-harm, suicidal thoughts, dissociation, and panic attacks. In one account a woman went into what seemed to be an anaphylactic shock during sex, despite the fact that she tested negative for allergies to several types of condoms, as well as more common allergens. Physical signs and symptoms of purity trauma, Klein says, are “abundant.”

Klein now works as a coach and runs Break Free Together, a non-profit for people recovering from religious trauma.

“There’s a lot of things that show up among purity culture survivors that confuse therapists, because therapists say: ‘You must have survived a capital-T sexual trauma,’ or ‘You must be a rape survivor,’ or ‘You must have experienced sexual abuse,’” she says. “In fact, many purity culture survivors have and don’t know it – a shocking number of people I work with over time are able to identify that they were sexually assaulted. Then there are other people who have not been assaulted, but who have so deeply internalized the teaching that it still shows up in their bodies.”

Treatment

Some therapists are already aware of the prevalence of anxiety and sexual dysfunction in some evangelical marriages. Rosie Tringham is a Christian relationship therapist in the U.K. She has worked with a number of married Christian women with vaginismus, and men with depression or anxiety symptoms around sex, such as panic attacks.

“When clients are disconnected from their bodies, they think that immediately on the honeymoon their sex life is going to start well,” she says. “There’s no reason they should think that – they’ve completely switched off.”

Anxiety symptoms can occur without physical abuse or assault, so Tringham considers them to be a trauma response to strict education around abstinence.

“As a psychosexual therapist I do a lot of work with the body in terms of trauma,” Tringham adds. “But I would say that sometimes when I ask a client [from an evangelical background] where they feel something in their body, a number of them say ‘I don’t know what you mean.’ After I explain, they may then start remembering that there were symptoms earlier on, but that at the time they detached from or suppressed their feelings.”

She says she has also seen clients who are unable to sustain relationships because of their church’s pressure to progress quickly to marriage. “There’s a lot of talk [in conservative Christian churches] about the body being the enemy, and you can’t trust it, and it must be punished and controlled,” she says. “We are wired for connection and yet people often spend years being separate, and not having it.”

Clinicians are beginning to look for signs of post-purity trauma too. At the nursing faculty at UCLA, Beth Schwartz is researching the effects of negative religious experiences on women – specifically purity culture – for a Ph.D. in nursing at Azusa Pacific University. Schwartz has personal experience of “deconstructing” purity teachings. Deconstruction (sometimes called “deconstruction therapy”) refers to a reflective practice whereby evangelicals re-evaluate long-held beliefs, often in the process of leaving evangelical Christianity.

She plans to develop a new theoretical framework for nursing that could provide screening tools and questionnaires for gynecological evaluations with purity survivors.

Meanwhile, experts from outside of the ex-evangelical community are starting to recognize how purity culture can contribute to physiological and psychological problems. At the University of Minnesota, behavioral health scientist Dr. Kristen Mark founded The Abstinence Project to do just that. Unlike many other researchers in this field, Dr. Mark does not come from a religious background.

The Abstinence Project aims to expose the harms of abstinence-only education through personal stories. Common themes include contracting STIs, dissociating during sex, and feelings of chronic guilt.

“Some other experiences that have struck me are things like feeling like the experience of sexual trauma was their own fault as a result of abstinence-only sex education, or feeling like having experienced sexual trauma meant they weren’t ‘worthy’ for another relationship,” Dr. Mark says. “Others include not getting any messages about anything other than sex for reproduction, so there have been stories submitted by gay men, for instance, about how they felt like their experience wasn’t ‘real’ sex.”

Recovery

Both Luke and Elizabeth have developed new attitudes about the teachings they were given as teenagers.

Elizabeth found a new church when she left home where she was able to deconstruct some of the teachings she’d learned as an adolescent. “Being in a more open space of conversation was quite healing,” she says. “But it was also bittersweet, because you see what you’ve experienced, earlier in life, and you realize: ‘That wasn’t OK’. I’m grieving for the hurt purity culture caused, and for what was lost.”

She continues to explore her faith and form new relationships. “I think dating is a great thing,” she says. “There is still that little bit of anxiety surrounding it, just because of things that are still internalized. Thoughts and feelings that I thought I’d figured out do sometimes crop back up. But it’s nowhere near as severe. I’m happy and comfortable with who I am now.”

Luke credits therapy as a useful process for learning more about the anxiety that had stuck with him into adulthood. He says, “I am married, I’m happy. These things still sit with me but they don’t have all the control anymore.”

He now works as the director for OneBodyOneFaith, formerly the United Kingdom’s Lesbian and Gay Christian Movement. (Luke and his husband were also the first same-sex couple to be married in a Baptist church in the U.K.)

“There is always hope,” he says. “Yes, the Church needs to be held to account for the way that it harms people. But for those who are harmed, there is the possibility for something else, another life to be lived.”

Ellie Broughton is a writer in London. She has written for The Guardian, The Independent, the i paper, Vice, and others.

*Elizabeth used a pseudonym.