Two-Spirit Indigenous Peoples Building on Legacies of Gender Variance

What Two-Spirit Peoples Can Teach about Transgender Identities, Religion, and Indigenous Communities

(Image by Michael Horse for the BAAITS Two-Spirit Powwow in 2012)

Conservative lawmakers have proposed more anti-LGBTQ legislation this year than ever before, and nearly a third of these laws specifically target transgender youth. Politicians say these laws will protect religious freedom and “traditional” family values. But transgender and non-binary people have a long history on this continent. Some Indigenous peoples refer to such individuals as Two-Spirit. As Candi Brings Plenty (Oglala Lakota Sioux) explains, “Two-Spirit people have always had a role to be a part of our ‘tiospayes,’ to be a part of our families, our extended families, our encampments.”

“Two-Spirit” is a contemporary term for Indigenous peoples who live outside the gender binary or who are not heterosexual or cisgender. People we now call Two-Spirit have existed for centuries and are part of long-held, and developing, Indigenous traditions of gender and sexual diversity.

Indigenous traditions of gender variance have much to teach the non-Indigenous world. For one, they disrupt the alleged universality of the gender binary. Indigenous concepts of gender also invite us to rethink assumptions about the supposed conflict between religion and trans and queer identities since Two-Spirit people are an active part of Indigenous life. And they challenge non-Indigenous people to expand our understanding of Indigenous peoples as important contributors to conversations about gender, religion, and “traditional” families in today’s world.

To understand Indigenous concepts of gender variance, we have to look to the past and the present. In some ways, the present is even more important given that Indigenous peoples are often thought of as existing only in the past. Because of this, Chippewa literary scholar Gerald Vizenor describes contemporary Native experience as “survivance,” a combination of the words “survival” and “resistance.” He labels it as “an active sense of presence, the continuance of native stories, not a mere reaction, or a survivable name.”

I have engaged with Indigenous political movements related to gender and sexuality as a scholar and participant. As a non-Native queer Latinx scholar, I study how colonization has shaped Indigenous genders, sexualities, and religions. I have also participated as an organizer for the annual Two-Spirit Powwow in San Francisco hosted by the Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirits. Following the work of non-Native scholar Scott Lauria Morgensen, I offer the following as part of a larger conversation with (and not for) Indigenous LGBTQ and Two-Spirit people, activists, and scholars.

Traditions of Gender and Sexual Diversity

For some Indigenous cultures, Two-Spirit people emerged at the time of creation. In an episode of the Netflix series “Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness,” Two-Spirit and non-binary cultural leader Geo Neptune (Passamaquoddy) recounts a creation story of the Wabanaki people. The story tells of the hero Gluskabe who shot an arrow at the brown ash tree, cutting both the tree and the tree spirit in half. This spirit now had two parts and agreed to be transformed into people. After Gluskabe breathed into the tree, the first Wabanaki woman and man emerged. “And after that,” Neptune explained, “there was just a little bit of each essence left over, so Gluskabe recombined them and sent the first Two-Spirit out of the tree. So, in our tradition we haven’t been separated from ourselves.” This is hardly the only such story within Native communities. Contemporary Two-Spirit and Indigenous LGBTQ people turn to these stories to remember that gender variance has always been a part of Indigenous traditions.

Indigenous traditions of gender variation illuminate pre-colonial understandings of gender before Christianity swept through the continent. Transgender Mohawk performance artist Aiyyana Maracle (1950-2016) speaks to this in her essay “A Journey in Gender.” She writes, “Though I may fit the definition of the European concept of transsexuality, as far as I am concerned, my being and transformation are based in the historical continuum of North America’s Indigenous people.” According to Maracle, this “continuum” draws from “a perception of gender that has existed, and continues to exist, quite apart from the prevailing Euro-North American norm epitomized by an inflexible, Christian, pseudoscientific declaration of one’s being as male or female.”

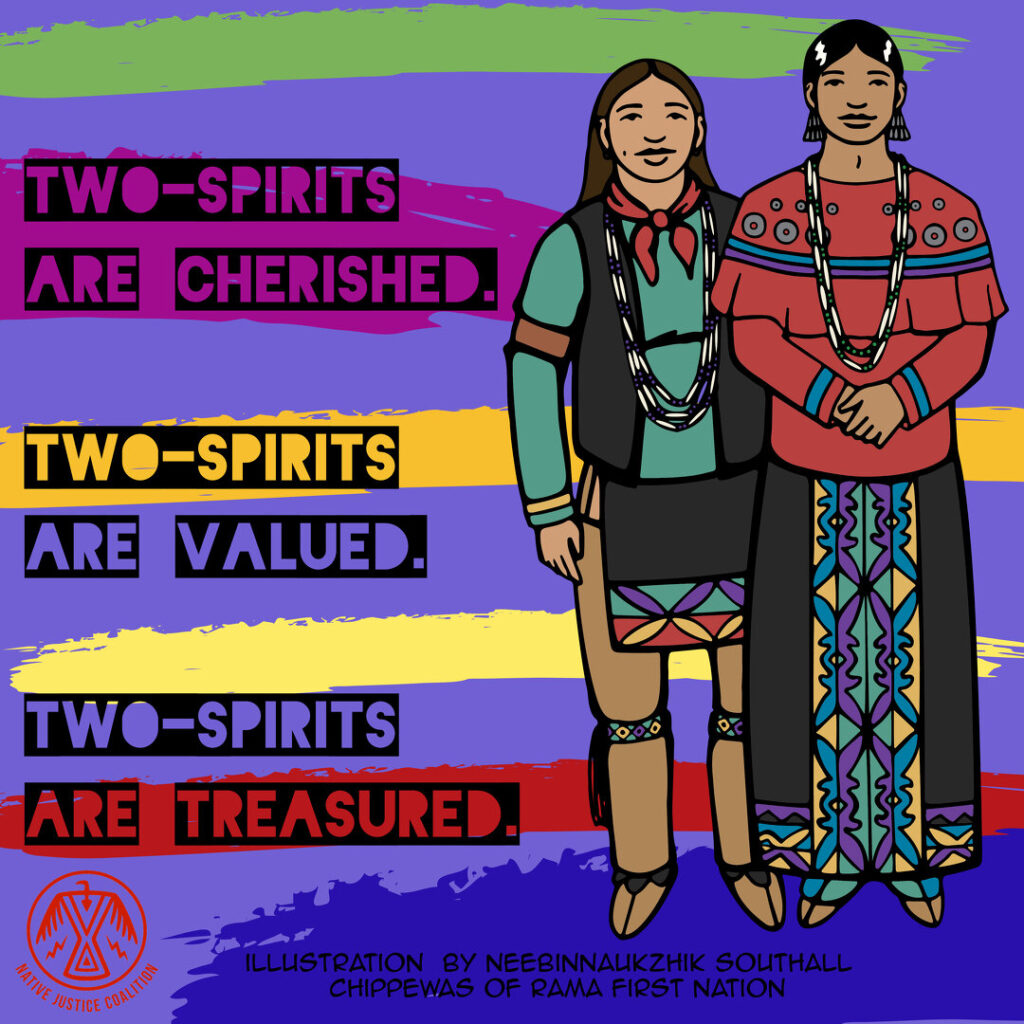

(Image source: Native Justice)

Concepts of gender vary across Indigenous communities, which are as diverse as the lands they inhabit. Native nations had (and have) distinct names for what we might call “trans” or “queer” people today. The Diné (Navajo) term is nádleehé, meaning “one who transforms.” Among the Lakota, the term is winkte, sometimes translated as “to be as a woman.” There are multiple terms in the Cree language, such as iskwêhkân, “one who acts/lives as a woman” and napêhkân, “one who acts/lives as a man.” In most cases, these identities were linked to social roles rather than biological sex. Historically, the people holding these identities took on esteemed positions as ceremonial leaders, warriors, storytellers, and healers.

Two-Spirit activist L. Frank Manriquez (Tongva, Rarámuri, Acjachemen) says that in Native California, “We permeated the sacred and the profane parts of life…Historically, we Two-Spirit have always been those who can do what others cannot do but need to be done.” Manriquez continues by saying that, “To some, Two-Spirit is strictly a spiritual thing. Two-Spirit[s] are the only ones who can bury the dead.”

Despite (or because of) the importance of Two-Spirit people, European colonizers directly targeted them. In California, as in other places, colonizers took Native lands and imposed their ideas about gender binaries and patriarchy. Two-Spirit literary scholar Deborah Miranda (Ohlone/Costanoan Esselen Nation) writes of the ways that “third gender people” experienced shaming, physical punishment, and erasure in the Spanish California Mission. The United States and Canadian governments also took a role in this through Indian boarding schools. In these schools, church leaders and government officials tried to assimilate Native children through a strict gender binary model. “Boys” were taught to engage in manual labor, while “girls” were taught to be domestics.

(Image of We’wha)

The most famous historical figure of Indigenous gender diversity is We’wha (c. 1849-1896), an Ihamana (third gender) person from the Zuni Pueblo in what is now New Mexico. Like other Ihamana, We’wha took on the cultural and ceremonial roles of both women and men in Zuni society. We’wha was known to be a particularly skilled weaver, potter, and spiritual leader. As an esteemed cultural ambassador, We’wha consulted with anthropologists and was even brought to Washington, D.C. in 1885 where they met with President Grover Cleveland. We’wha is remembered today as an important Two-Spirit figure who advocated for Zuni people while the U.S. was trying to assimilate Native peoples and take even more of their lands.

White academics were fascinated by the gender and sexual diversity in Native nations, although they regularly misunderstood what they were observing. In the 20th century they used the term “berdache” to describe those they perceived as homosexual, cross-dressers, and transgender, and especially those we might call male-assigned-at-birth in domestic and sexual relationships with men. For these academics, “berdache” had a negative connotation; the word’s origins in Arabic and French suggested such meanings as “kept boy” and “male prostitute.”

Since “berdache” was an external term applied to Native Americans, Indigenous people sought to find their own label that better reflected their histories and traditions. They adopted the term “Two-Spirit” in 1990 at the International Gathering of American Indian and First Nations Gays and Lesbians in Winnipeg. “Two-Spirit” is a translation of the Anishinaabemowin word Niizho Manidook. This term came to elder and academic Myra Laramee (Fisher River Cree Nation) in a dream before being adopted at the 1990 gathering. Laramee recounts that the dream included seven orbs of light, which transformed into male and female faces. “And the first time the grandpa came, the mooshum face came, he said, ‘You are as of us. You are one of us and you have been here like us since the beginning of time and you have come to know… how we travel the earth and the sky world, and the spirit world,’” Laramee recalls. This voice said, “‘You will begin to know many different kinds of things about the Two-Spirit Nation. It’s a nation of many means and many gifts and many ways. But the easiest and best way, is to see that your gift is to see the world always in two sights, with two feelings of the heart.’” While often defined as a person with a masculine and feminine spirit, some Two-Spirit people emphasize that the term instead refers to what Laramee describes as a person with “two sights.”

“Two-Spirit” is a specifically Indigenous concept of gender and sexuality; non-Native people should not apply the label to themselves. Trans social media influencer and scholar Charlie Scott (Diné) argues, “it would be inappropriate to use this phrase, this concept, this being as an explanation for other communities, especially because they have their own meaning, their own cultural context, their own understanding of themselves within their own communities.”

Continuity, Expansion, Transformation

Two-Spirit people are active in transforming Native communities, some of which became entrenched in the gender binary and homophobia following colonization. As such, Two-Spirit people identify in a variety of ways. Some use nation-specific terms like nádleehé. Others may refer to themselves with mainstream designations like “LGBTQ” in addition to Two-Spirit. Because of this, there is not always a direct correlation between “transgender” and “Two-Spirit” identities. In an open letter declining the Lambda Literary award in “Trans Poetry,” poet Joshua Whitehead (Oji-Cree) writes of his objection to being labeled “trans,” saying, “My gender, sexuality, and my identities supersede Western categorizations of LGBTQ+ because Two-Spirit is a home-calling, it is a home-coming. I note that it may be easy from an outside vantage point to read Two-Spirit as a conflation of feminine and masculine spirits and to easily, although wrongfully, categorize it as trans.” Like Whitehead, many Two-Spirit people embrace the term “Two-Spirit” because it allows for a more robust, culturally-grounded identity that cannot fully be captured by mainstream understandings of “LGBTQ.”

In a similar way, Two-Spirit identities are often about “coming in” to a cultural identity rather than “coming out.” Literary scholar Qwo-li Driskill (Cherokee) argues that unlike many non-Native queer movements that frame queerness as oppositional to mainstream society, Two-Spirit people situate their identities in the worldviews of Indigenous peoples. To be Two-Spirit is to embrace Indigenous practices and one’s place within the culture. As education scholar Alex Wilson (Opaskwayak Cree Nation) put it, “As a self-identifier, two-spirit acknowledges and affirms our identity as Indigenous peoples, our connection to the land, and values in our traditional culture that recognize and accept gender and sexual diversity.”

Despite the rich history of gender and sexual diversity in Indigenous communities, homophobia and transphobia persists in some areas, largely as a result of Christianity and colonization. Diné trans community leader Yuè Begay grew up on the Navajo Nation reservation. She explained, “I think it would be kind of naïve to say that because I grew up in rural settings, it was all glitz and glamours, [that] I had medicine people roll out the red carpet for me because I was Two-Spirit. That didn’t happen. On the reservation, you pretty much do experience, in some cases, extreme effects of colonization because it’s by your own people, because it cuts so deep because it’s from your own elders.” This can include transphobic shaming or exclusion, which are direct results of colonization. This is important to note so as to not idealize Indigenous communities. Some Two-Spirit and trans people feel accepted in their home communities. Others work to transform settler-imposed ideas of gender and sexuality as part of decolonization.

Two-Spirit people have worked to expand their cultural traditions in many ways. One example is how they have re-conceived some traditional ceremonies. Alex Wilson writes that, according to some Native oral teachings, the drum is feminine and is the heartbeat of the Earth, but that only men should drum. Wilson continues, “This latter assertion (which takes power from and regulates the bodies of women and two-spirit and trans people, and simultaneously privileges men) is typically presented to our children at a very early age and entrenched as a ‘traditional teaching’ by those in our community who enforce gender specific protocols at ceremonies and celebrations.”

In the San Francisco Bay Area, Two-Spirit people received their own drum in 2010. Drum keeper Phoenix Lara (Yaqui) said, “it was unheard of to have Two-Spirits have their own drum, especially here in the west coast. So, this is like really having broken ground by having our own drum. And so, part of that has been to have been teaching songs…learning. We have been reclaiming our traditions. We hold drum circles every month.” In these drum circles, participants sit around a large drum and beat the drum with a drumstick while offering traditional songs and prayers. They also burn sacred plants like sage or cedar. Though Two-Spirits have been excluded from participation in some Indigenous spaces, Lara mentioned that this drum allows Two-Spirits, their families, and allies “to be part of the circle and to reclaim your traditions and [to] also have an opportunity to create new traditions as well.”

The drum Lara describes is affiliated with the community organization Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirits. “Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirits (BAAITS) exists to restore and recover the role of Two-Spirit people within the American Indian/First Nations community by creating a forum for the spiritual, cultural and artistic expression of Two-Spirit people,” according to their website. BAAITS made history in 2012 by hosting the world’s first public Two-Spirit Powwow in San Francisco. A powwow is an Indigenous gathering where songs and dances are shared with community. Though not explicitly a religious ceremony, powwows often include important religious elements such as prayers and drums. Many powwows feature gendered dances, such as the jiggle dress dance for women. At the BAAITS powwow, however, all the dances are de-gendered to allow people of any gender to dance when they see fit.

(Image: BAAITS Powwow. Source: crazycow.com)

The BAAITS Powwow offers an important space to celebrate Two-Spirit people, a respite from the transphobia and homophobia some feel both inside and outside of Native spaces. BAAITS board member J. Miko Thomas (Chickasaw), a.k.a. drag persona Landa Lakes, remembers the experience of exclusion while attending the large Red Earth powwow in Oklahoma in the 1980s. Thomas said, “So it felt really empowering to me the very first time that we…Sorry. [Holds back tears.] We as the organizers really stress very, very much that it has to be welcoming, that everybody in our community is welcome.” Thomas added, “I think that if anything, if we could change the lives of those young Two-Spirits who are afraid now, and who are so scared of being shunned or unloved by their own parents, then I think it’s important to have spaces like this so that people can see that we are a part of the Native community. And we’re just like everybody else.”

Two-Spirit powwows are now held across the United States and Canada.

Survivance and Solidarity

“Indigenous and trans women have been at the forefront of Indigenous and queer issues since we have had to fight to exist. Since colonization, we have survived through the genocide of both of these worlds — and we will survive this. Through community and kinship, we will create new possibilities for love,” writes trans and Two-Spirit poet Arielle Twist (Cree).

Two-Spirit and Indigenous trans people continue to experience the colonial ramifications of transphobic violence, land dispossession, and the ongoing crises of missing and murdered Indigenous women. But their lives are not just violence; they also embody “survivance.” They continue a long history of gender variance and fluidity embedded in Indigenous stories, ceremonies, and languages.

Two-Spirit survivance calls each of us to engage in ongoing and self-reflective work of community building to dismantle both transphobia and settler colonialism. This can take different forms. Kai Pyle (Métis/Sault St. Marie Nishaabe), a trans and Two-Spirit scholar, notes that for Indigenous peoples, this can include relationship-building within Indigenous nations with their trans and Two-Spirit community members, creating new traditions for trans people, and ensuring connections between trans Indigenous peoples and their homelands. For Non-Native peoples, Scott Lauria Morgensen writes, this work can include challenging the colonial roots of gender binaries, heterosexism, and patriarchy. Most importantly, he urges non-Native peoples to enter into relationships of solidarity with Native struggles towards decolonization.

Considering Two-Spirit survivance invites us understand the complex intersections of religion, colonialism, and gender. It also opens new possibilities for decolonial futures. As Kai Pyle writes, “It is only by facing head-on the realities of trans Indigenous people’s lives and by working on building decolonial loving relationships that we will begin to find a way to create a world that embraces all of us.”

Abel R. Gomez is Assistant Professor of Native American and Indigenous spiritual traditions in the Religion Department at Texas Christian University, located on the homelands of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes. His research focuses on sacred sites, ceremony, and (de)colonization in the context of contemporary Indigenous religions.