Polygamy, Incest, and Mormons in the Media

The problem of incest within Mormon fundamentalist communities, in portrayals on shows like Under the Banner of Heaven, and in the legal system

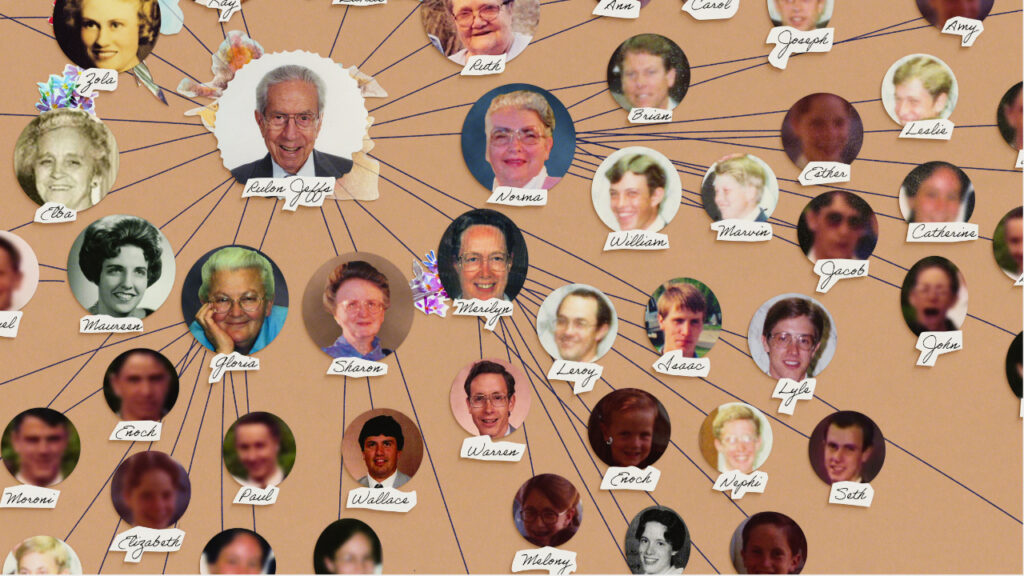

(Image source: Netflix’s Keep Sweet, Pray, and Obey)

Part I

In 2003, Jeremy Kingston pled guilty before the Third District Court of Utah to an illegal sexual relationship with a minor. The “relationship,” more aptly described as ongoing rape, was between Kingston (then 24) and his 15-year-old cousin, LuAnn Kingston. During the trial, Kingston testified that “he had a sexual relationship with LuAnn Kingston starting when she was 15 and that she was his first cousin.” He further admitted that “his mother and LuAnn Kingston’s mother are sisters, and her father is his grandfather.” The trial ended with Kingston receiving a five-year prison sentence, of which he served a mere nine months.

Jeremy Kingston is a member of the Davis County Cooperative Society or “Kingston group,” a Mormon fundamentalist group with a history of incestuous marriage. Activists and scholars at the Southern Poverty Law Center have documented multiple cases of incest based on information from former community members. Rolling Stone reported similar cases, which recounted the group’s doctrinal justification for the abuse. For members of the faith, the practice is a matter of perceived necessity to retain a particular bloodline based on their belief that the group’s early leaders had a direct lineage with Jesus Christ.

Jeremy Kingston’s trial for felony incest made headlines for many reasons, including the rarity of the conviction. For years, former members of the Kingston group sought prosecution for incestuous marriages with little success. Jeremy Kingston’s prosecution offered brief hope. Around the time of the trial, former members of the community approached Utah Attorney General Mark Shurtleff about incest in the community and put together a “family tree” to document the crimes, saying they had “compiled enough incest evidence to lock” up the perpetrators “for life.” But no prosecutions took place.

In Jeremy Kingston’s case, the public’s main concern was the age of the young woman, not her familial relationship to the perpetrator. To the disappointment of survivors, incest never seemed to warrant its own prosecution. This too-common problem is rooted in the historic conflation between Mormon polygamy and incest, and media depictions of both. Scholars and activists have long discussed the issues that stem from the perception that Mormon polygamy and incest are one in the same. Consequently, prosecutors rarely take legal action to target incest within polygamous communities, allowing it to continue unpunished and with little legal recourse for survivors.

Part II

Beginning in the nineteenth century, American opponents of polygamy sought to conflate the practice with criminal behavior, such as incest, to portray Mormon plural marriage as inherently deviant, dangerous, and worthy of prosecution. Since 1933, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) has not permitted polygamy. But polygamy remains a central tenet for many other communities that trace their founding to Joseph Smith. As opposed to the LDS Church, these communities believe they are upholding the fundamentals of Smith’s teachings, including polygamy, and are therefore commonly called Mormon “fundamentalists” to denote their separation from the LDS Church headquartered in Salt Lake City. Today’s debates over polygamy center on Mormon fundamentalists.

Legal prosecutions for polygamy have always been fraught, despite great efforts to imprison polygamists. There are many reasons for this, but one main reason is logistical. There are not enough police or prisons to prosecute the 35,000+ polygamists in the Intermountain West, and adding that level of policing is an unpopular public policy.

The concern over polygamy generally, and Mormonism specifically, stemmed from widespread concerns in 19th-century America over “correct” and “civilized” marriage. From the onset of public debates over correct marriage, ministers and government leaders who were concerned with the morality of the nation questioned the permissibility of relationships between close family members. These debates sought to articulate a universal norm for marriage, which was complicated by biblical accounts of incest.

The earliest regulations over incest treated the practice as a sin, rather than a crime. Pulpits, not courtrooms, were the center of the debate, which included questioning which marriages constituted incest. Could an uncle marry his niece? Could two cousins marry one another? As religious leaders debated these questions, legislators rarely included incest in case law. Instead, for many Americans, incest was a disgrace relegated to the shadows that acted as a metaphor for a “bad marriage,” a “bad family,” and “bad religion.”

(Photo of an early polygamous family. Image source: The Guardian)

Mormons themselves were not part of these public debates. However, their polygamous marriage system soon became a central concern that escalated to the United States Congress and Supreme Court. It didn’t help that Mormons began practicing polygamy as the national debate over marriage reached its peak between 1842 and 1846. Some Mormon historians date the revival of plural marriage to 1831, the year Joseph Smith began studying the Old Testament and became intrigued with the biblical patriarchs’ practice of polygamy. Akin to the polygamous leaders of old, Smith believed he was called to reintroduce the practice as part of the “restoration of all things.” It was not until over a decade later, on July 12, 1843, that Smith recorded what became Doctrine and Covenants 132, which laid the foundation for Mormon polygamy and the idea that families are sealed in an eternal union. While Smith linked polygamy to the restoration of Abraham’s marriage system through the Law of Sarah, Smith’s teachings failed to mention one crucial thing: Sarah was Abraham’s half-sister. Even more, the presence of incestuous marriages in the Bible is extensive. For this reason, it is perhaps not surprising that Americans concerned with Mormon polygamy also came to associate the practice with incestuous marriage.

The first allegations of Mormon incest appeared in anti-Mormon accounts of the faith. Among the most significant cases were documented by Catherine Lewis, a woman who joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in its earliest years and left when rumors circulated that others were practicing polygamy. In her 1848 exposé, she described a young woman pressured into an incestuous marriage who told Lewis, “I was young, and they [Mormon leaders] deceived me, by saying the salvation of our whole family depended on it. I say again, I will never be sealed [married] to my Father; no, I will sooner be damned and go to hell, if I must.’” Tales like this fueled anti-Mormon sentiment across the country.

While salacious accounts of incestuous Mormon marriages circulated throughout the nation and its western territories, leaders of the Church soon made their own apologetic claims for the practice. Between 1852 and 1854, Brigham Young, the President of the LDS church following Smith’s death, made several statements that supported the possibility of incestuous marriage. In a February 22, 1852 sermon, Brigham Young explained, “This is something pertaining to our marriage relation. The whole world will think what an awful thing it is. What an awful thing it would be if the Mormons should just say we believe in marrying brothers and sisters. Well, we shall be under the necessity of doing it, because we cannot find anybody else to marry. The whole world are at the same thing, and will be as long as man exists upon the earth.” Following this pronouncement, incestuous marriage did not become a widespread practice, save for a handful of cases. But with these words, Bringham Young sanctioned the possibility.

In time, Young’s comments became proto-eugenic. The early Mormon church had taught that race was a sign of righteousness or wickedness, and the church encouraged “correct” marriages among whites. Mormon “sealing” was therefore not simply about marriage. It was about the ability to unite powerful, white families. Drawing on this, Young and others argued for a pure bloodline that stemmed from polygamous unions among and between influential Mormon families.

Young’s words and those of anti-Mormon detractors united polygamy with incest in the minds of many Americans. Outsiders invoked the “ultimate taboo” to disparage Mormonism and deride their controversial marriage practices. Whether or not Mormons participated in marriages with close family members was unimportant. The conflation between their marriage system and America’s most taboo sexual relationship ostracized Mormons and stigmatized them for decades.

Part III

Subsuming incest stories into accounts of polygamy did not end in the nineteenth century; it continues today. FX and Hulu’s recently released and Emmy-nominated series, Under the Banner of Heaven, is one such example.

Banner is based on the true-crime bestseller about Ron and Dan Lafferty, two brothers who made headlines after the 1984 double murder of their sister-in-law, Brenda Lafferty, and her infant daughter, Erica Lane Lafferty. The men were raised in the LDS Church. However, in the 1970s, the men joined a fringe Mormon group led by a man named Robert Crossfield (Prophet Onias), also a former member of the LDS Church. The group, called the School of the Prophets, understood itself to be an authentic remnant of the religion founded by Joseph Smith. They were one of the many Mormon fundamentalist groups to promote polygamy.

Banner is based on the true-crime bestseller about Ron and Dan Lafferty, two brothers who made headlines after the 1984 double murder of their sister-in-law, Brenda Lafferty, and her infant daughter, Erica Lane Lafferty. The men were raised in the LDS Church. However, in the 1970s, the men joined a fringe Mormon group led by a man named Robert Crossfield (Prophet Onias), also a former member of the LDS Church. The group, called the School of the Prophets, understood itself to be an authentic remnant of the religion founded by Joseph Smith. They were one of the many Mormon fundamentalist groups to promote polygamy.

As the Lafferty brothers entered Robert Crossfield’s orbit, they became interested in polygamy and sought to practice the early Mormon doctrine. By the time of the murders, Crossfield advocated for incestuous marriage and married at least one of his biological children. At the time, this was not uncommon. Several Mormon fundamentalist leaders who emerged in the 1970s and 80s engaged in incestuous relationships. Most notably, Ross LeBaron and Fred Collier, men who led their own Mormon fundamentalist communities, justified incestuous marriage and became key figures in the argument that polygamy was merely incest by another name. In the revelation that catalyzed incest in his family, Robert Crossfield referred to his daughter as a “handmaid,” a term used in reference to Joseph Smith’s wife in Doctrine and Covenants 132. Crossfield used this language to justify marrying his daughter, a crime that still haunts Crossfield’s descendants.

Like Crossfield, Dan Lafferty’s attempt at a polygamous union involved grooming his own daughter to marry him. According to the book and series, Dan’s wife, Matilda, walked in on her husband giving a chiropractic adjustment to their daughter that concerned her. After confronting Dan, Matilda learned of Dan’s “vigorous sexual spirit” and his plan to marry their 12 and 14-year-old daughters as plural wives. Fearing for the fate of her daughters, Matilda snuck them out of their home. The local LDS leadership subsequently ex-communicated Dan. (Following the show’s release, Dan Lafferty’s daughter, Rebecca, announced her plans for a book that details her experience growing up under her father’s abusive family headship, where she witnessed her father sexually abuse her sisters.)

The disturbing realities of incest within the Lafferty story were mostly overshadowed by the murders, leaving other Lafferty victims in the shadows. In Banner and elsewhere, incest became a plot device that solidified a villain for the audience. This is not new. In media portrayals of polygamous Mormons, incestuous abuse often acts as a metaphor for human depravity and the outcome of polygamy’s slippery slope. The problem, in Banner and elsewhere, is that incest is not merely a plot device to signal a villain’s depravity. Incest is real, pervasive, and can be profoundly damaging.

Part IV

In her reflections on Banner, Lindsay Hansen Park, a historical consultant for the show, explained, “The series isn’t an indictment on fundamentalism, but it is an indictment on secrets.” The persistence of incest in Mormon fundamentalism is one of those secrets.

While mainstream media has given some attention to fundamentalist Mormon incestuous marriages, too often, as with Banner, those media portrayals fail to center victims of incest or demonstrate why legal action is necessary. Most recently, Netflix’s docuseries Keep Sweet: Pray and Obey explores Elissa Wall’s experiences in the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (FLDS) and documents the lives of other survivors from the FLDS. The FLDS, led by Warren Jeffs, garnered media attention years ago following a widely televised raid on the community that was an attempt to save the children from polygamy. Jeffs faced allegations of incest. But those allegations were not prosecuted despite Elissa Wall’s testimony of forced marriage to her cousin at the hand of Jeffs in Nevada — a state where incestuous marriage is illegal.

***

In her writings about media portrayals of minority religious groups, religion scholar Megan Goodwin has argued that polygamy is not necessarily abusive. This is true. Nor is monogamy inherently free of abuse. But in the United States, polygamy is practically synonymous with harm and heinous behavior. This was the same rhetoric used to deride Mormons in the early decades of the new religion. And today, media accounts too often use polygamy and incest as a storyline device to bolster villain storylines. The conflation encourages gawking disapproval and nothing more.

As a country, both in our media and in our legal system, we have overlooked survivors of incest and kept the totality of their stories hidden from the public eye. Stories about polygamy collapse incestual abuse into a historically demonized marriage system, causing survivors of incest to disappear. Incest remains a widespread reality in insular polygamous communities. Taking survivors of incestuous abuse seriously requires untangling how the nation conflated abuse, marriage, religion, and family in our history and media.

In 2020, Utah took the first step toward this disentanglement. Senate Bill 102 effectively decriminalized polygamy, lowering the criminal status to an infraction if the participants are not involved in other criminal behavior. The legislation sought to end polygamy’s conflation with incest, as well as other crimes associated with these controversial marriages. The goal was increased reporting and access to social services for victims and survivors. Since the time of the bill’s passing, one non-profit stated that sexual abuse reporting doubled in the polygamous communities they serve. The numbers make tangible the gravity of the problem. Ending the conflation between polygamy and incest will begin the process of justice for survivors, and other states must do the same now.

Cristina Rosetti is an Assistant Professor of Humanities at Utah Tech University. Her research focuses on the history and lived experience of Mormon fundamentalists in the Intermountain West.