Not So Sorry

Christianity Today’s Sexual Misconduct Problem and the Complications with Forgiving Institutions

Should we forgive institutions when they admit to years of abuse?

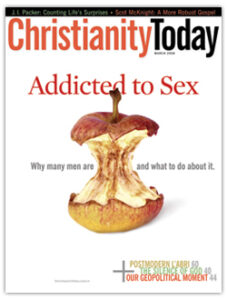

(Image source: Christianity Today)

Construction noise is a constant background in the soundtrack of our American impulse for self-improvement. Lately, however, that sounds less like buildings going up and more like the toppling of statues and the chiseling of buildings that represent our problematic history. At U.C. Berkeley, where I teach writing, many of our buildings have been experiencing an overhaul. Yes, one of the most dangerous earthquake fault lines in California runs right through the middle of campus and some of those buildings are aging, crumbling, and in need of earthquake retrofitting. But a simultaneous building rejuvenation reflects the university’s attempts to correct mistakes of the past. In a scene playing out on campuses around the country, maintenance crews are peeling, grinding, and chiseling the names off of numerous academic buildings.

One of my classes currently meets in the Social Science building, known until last year as Barrows Hall. David Prescott Barrows was an anthropologist who wrote multiple racist screeds against Black and Filipino people. Berkeley’s Building Name Review Committee voted to strip his name from the six-story building that is ironically home to the Ethnic Studies department. Barrows and the others whose names are being removed are long dead, so it is impossible for them to ask for forgiveness. The university, instead, must stand in for individuals.

Institutions are increasingly forced to ask for forgiveness on behalf of people both living and deceased. The process is frequently arduous and clunky, and the results often unsatisfying for living victims or their descendants.

Recently, the American evangelical flagship magazine Christianity Today shocked thousands of people by dropping a surprise story in which Christianity Today reporter Daniel Silliman revealed that, for over 12 years, female employees had experienced sexual harassment from former editor-in-chief Mark Galli and former advertising director Olatokunbo Olawoye. According to the current Christianity Today editor-in-chief Timothy Dalrymple, Silliman was invited to write this investigation by the magazine’s editors. At the recommendation of abuse victim and attorney Rachel Denhollander, Christianity Today also hired Guidepost Solutions, a business consulting company, to investigate the abuse claims and make recommendations. Silliman did not see the Guidepost report until after he had concluded his own reporting. The magazine, according to both Silliman’s article and Guidepost Solution’s report, had done little if anything to mitigate the abuse.

The story of how all of this unfolded is highly unusual in journalism. Unlike the Boston Globe reporting on clergy abuse in the Catholic Church, the timing and circumstances of both Christianity Today’s reports surfacing at once is curious. Oftentimes, when an institution reports on its own failings, it is doing a form of public relations to get ahead of and shape the story before an outsider reveals the unvarnished problems.

Christianity Today, founded by Billy Graham in the 1950s, has had a large readership, making it a powerful voice for conservative Protestant values around issues of sex and sexuality. It has also been primarily led by men, and, statistically, men are far more likely to sexually harass women than vice versa. The response to Silliman’s report that female staffers were groped and verbally abused was explosive on social media. Even in the post-Trump era, white evangelical culture remains a subject of fascination for many outside of it.

Christianity Today, founded by Billy Graham in the 1950s, has had a large readership, making it a powerful voice for conservative Protestant values around issues of sex and sexuality. It has also been primarily led by men, and, statistically, men are far more likely to sexually harass women than vice versa. The response to Silliman’s report that female staffers were groped and verbally abused was explosive on social media. Even in the post-Trump era, white evangelical culture remains a subject of fascination for many outside of it.

Unlike the Catholic Church, where abuse cases must at least theoretically be reported to central bodies like diocesan offices, evangelical churches have no center of power akin to Rome and there is often no one like a bishop supervising the behavior of pastors. Often, there is little, or no, accountability for pastors beyond their congregations. Unfortunately, according to Silliman’s reporting, that structure — with a powerful man at the top and everyone else below — was replicated at Christianity Today. And powerful men, no matter their religious background, are most concerned with protecting themselves.

In Silliman’s report, most of the harassment cases disclosed to Human Resources were buried or pushed aside, but much of the harassment never even made it to HR. In one disturbing incident, a woman whose sexual harassment was reported to HR by a colleague found herself on the receiving end of a stream of grievances from former editor Mark Gailli, who accused her of seeing “everything” as sexual harassment. Amy Jackson, a former associate publisher who left the magazine in 2018 due to what she described as a “hostile work environment,” told Silliman that “the culture when I was there was to protect the institution at all costs.”

Anyone who remembers Jim Bakker, Jimmy Swaggart, Doug Phillips, or any other name on the long list of evangelical pastors who were involved in sex scandals knows there is a pattern among powerful evangelicals preachers that often leads to abuse coverups. In addition, the #ChurchToo movement started by evangelical women who were victims of abuse has also made it clear that these patterns of abuse and coverup are more extensive than many people had previously known. The issue at Christianity Today, too, seems to be a consistent pattern of denial that anything was wrong. Guidepost Solutions, the consulting firm hired by Christianity Today, reported that the publication’s “flawed institutional response to harassment allegations could have been influenced, in part, by unconscious sexism,” and that some of the problem may have stemmed from older men “out of touch with current workplace mores.”

For his part, Galli, who retired from Christianity Today in 2019, sounded defensive in an interview with Religion News Service’s Bob Smietama, in which Galli claimed that the stories in Silliman’s report were “taken out of context” or “simply not true.” Galli left evangelicalism behind when he retired from Christianity Today, ironically converting to Catholicism, a denomination with its own history of abuse and denial. Olayowe, on the other hand, was fired by Christianity Today in 2017 after being arrested in a sting operation and pleading guilty to meeting a minor for sex. He did three years in prison and now lives as a registered sex offender.

***

When we’re thinking about the idea of forgiveness, the Christianity Today story leads to two overlapping questions: who is really at fault here, and should they be expected to seek forgiveness? In his editor’s letter that accompanied Silliman’s report, Timothy Dalrymple said the whole process had taken place out of a greater need for transparency. “We owe it to the women involved to say we believe their stories,” Dalrymple wrote, “and we are deeply sorry the ministry failed to create an environment in which they were treated with respect and dignity.” Dalrymple had just come on board as editor-in-chief when some of these accusations began to surface in 2019, and more women continued to come forward in subsequent years. All evidence seems to indicate a series of miscommunications and a problem with the institutional culture of the magazine and of evangelicalism, rather than responsibility residing with a single person. Dalrympe’s apology is straightforward and accompanied by promises for greater accountability. Time will tell how or if that manifests at Christianity Today, but evangelical notions of forgiveness may make maintaining that promised transparency a challenge.

In an interview with Slate’s Molly Olmstead after the report was released, Silliman talked about what forgiveness means for evangelicals like himself. From an evangelical perspective, Silliman says, “there is an idea that in any kind of personal conflict or disagreement or even harm, the ultimate aim for Christians should be the reconciliation of the two parties.” Silliman goes on to say that one of the accused men he reported on seems to believe that “a true Christian should not report stuff if it gets in the way of reconciliation.” Journalists who publish such reports, according to this logic, hamper possibilities for forgiveness and reconciliation.

(Image source: Christianity Today)

That pattern of blaming members of the media for spending too much time reporting on abuse and too little time focusing on stories of reconciliation is not new and not even a particularly evangelical pattern. Back in 2003, now-Archbishop Wilton Gregory, formerly the head of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, told reporters that while reporting on abuse was helpful in creating more accountability, “the way the story [of abuse] was so obsessively covered resulted in unnecessary damage to the bishops and the entire Catholic community.” Gregory neglected to consider that many of those reporters were themselves Catholics and perhaps invested in holding an institution they cared about accountable, much like Silliman.

But a reason reporters might not be focusing on stories of reconciliation between abuse victims and church-led institutions is simply because there are not many stories about reconciliation and forgiveness to tell. Over and over, institutions like the Catholic Church, Christianity Today, and universities big and small have apologized for covering up, hiding, and abetting abuse in many forms. Very rarely do abuse victims announce that they have forgiven the institution and are ready to move on. Perhaps that is because the institution has not earned and is not owed any forgiveness.

Christianity Today’s self-investigation was received with varying degrees of emotions on social media. Author Kathy Khang wrote “sadly, I’m not surprised.” Union Seminary professor Isaac Sharp also pointed to institutional failure as a root cause, saying evangelical culture has a “systemic sexual abuse problem that will continue virtually unchecked” while leaders fail to acknowledge “the reality of structural evils.” Pastor and writer Eric Atcheson called it a “huge red flag” that Christianity Today had reported on its own abuse cases, saying this wasn’t a case of transparency so much as an example of “zero meaningful external accountability.” And former Christianity Today managing editor Katelyn Beaty added that she had herself witnessed some of the abuse at the magazine, but as “a young woman in her first job,” she was unclear about what to do to stop it and instead hoped the men in charge – some of them later accused of abuse – would be the ones to do something. She added that while she hoped to see change, she was watching to see if current editors would “rise to the occasion or crouch in defensive protectionism.”

It also didn’t escape the eyes of many on social media that Christianity Today released this report right after it launched a hugely successful podcast called The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill, an investigation of the evangelical megachurch in Seattle led by Mark Driscoll. Driscoll, who was known to scream and swear during sermons, also had a habit of describing women as sexually submissive in graphic detail. But Mars Hill was so financially successful that people looked the other way until Driscoll irreparably upset his followers by plagiarizing extensive portions of his books.

According to some listeners, however, the podcast pointed fingers at everyone but Driscoll himself, reflecting that same institutional pattern of protecting the powerful. In Religion Dispatches, Jessica Johnson called this “gaslighting at the scale of population” and “a systemic problem for an insatiable evangelical industrial complex.” Mars Hill’s elders and congregation seemed to look the other way when Driscoll shouted abuse at people. But the public exposure of plagiarism, which risked the financial well-being of the church profiting from Driscoll’s book sales, was apparently a bridge too far. If Christianity Today were assessing its own issues of how it handled abuse at the same time it was producing an ethically troubling podcast about another case of abuse, can Christianity Today be trusted? Time will tell.

But institutions rarely follow best practices when they are accused of abuse. When these reports surface, transparency and accountability are paramount. But an apology and promise to do better are not enough to earn an institution forgiveness. Until these things are accompanied by some form of action, whether that’s public accountability, reparations, abusers stepping out of the public eye, or following the principles of restorative justice to prevent future harm, no institution or individual is owed forgiveness.

***

When an abusive person’s name is drilled off a building, the shadow of the old name often remains visible even when a new one is mounted on top of it, gouges in the surface that never fully fade away. The same can be said about institutions with histories of abuse. Apologies may be offered, but the shadowy history is now visible to everyone, hiding in plain sight. And abuse being visible to everyone does not mean it deserves to be forgiven. It just means we are able to see it more clearly when it inevitably happens again.

Kaya Oakes is the author of five books, most recently including The Defiant Middle: How Women Claim Life’s In Betweens to Remake the World. She teaches writing at the University of California, Berkeley and writes the Revealer‘s column, “Not So Sorry.”