Secular Sex and Social Justice

Kali Handelman interviews Janet Jakobsen about her book The Sex Obsession and what it can teach us about today's political dynamics

In the few weeks since I finished reading Janet Jakobsen’s new book The Sex Obsession: Perversity and Possibility in American Politics (NYU Press, 2020) I have referenced and recommended it in no fewer than a dozen conversations. It’s a too-rare example of scholarship that is rigorously complex and also genuinely accessible — a form that embodies the book’s own arguments. Jakobsen’s book is remarkably timely, providing histories of our present that offer rich, hopeful, and challenging ways of thinking and acting toward critical new horizons. She is also very fun to talk to (fun being not at all incidental to the project, as readers will see).

***

Kali Handelman: First, I’d like to ask you about how the project took shape. What was the genesis? It feels like a project that was both cumulative and collaborative, that you are thinking with your partner, Christina Crosby, with your Love the Sin co-author, Ann Pellegrini, and with your comrades at the Barnard Center for Research on Women (BCRW), and that doing so — writing it in this way — was a way of queering (to use the verb as you invite your reader to) the book writing and publishing process in order to make strong arguments and strong claims about how we can and should think and work together. The book also felt like a response to your years of movement work and to the present political moment — I’m thinking of how you critique liberal intellectuals like Thomas Frank and Andrew Sullivan who, frankly, seem to piss you off (as they do so many of us). I could imagine you reading the New York Times opinion section and, in productive pique, thinking to yourself, “there’s one for the book!” The book is also impressively accessible — written clearly, with strong metaphors, without compromising nuance and complexity — it seemed like you were aiming for a wide audience. To put all of this as a question: Can you tell us about how this project came to be?

Janet Jakobsen: I’d like to say thanks to you, Kali, for such a great reading of The Sex Obsession and to the Revealer for hosting this interview. You’re exactly right that this book was built through collaborations and relationships that go back a while now. I was trained in religious ethics and one of the prominent methods in the field is the study of practicing communities: How do people realize their ethical commitments in practice? What can we learn about ethical commitments by learning what people actually do? This method calls out for collaboration. I’ve been part of a range of interdisciplinary collaborative projects, including co-writing and co-editing (with Ann Pellegrini most often, and also with Elizabeth Castelli on religion and violence, historian Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy and sociologist Elizabeth Bernstein, and now with Christina Crosby on disability and care). And, particularly through my work at the Barnard Center for Research on Women, I pursued this method by collaborating with activists and artists who were not just organizing for social justice, but also creating new knowledge, developing and elaborating paradigms for undertaking organizing and for social analysis — as Amber Hollibaugh, Catherine Sameh and I wrote for one project, knowledge can be part of “changing how change is made.”

Janet Jakobsen: I’d like to say thanks to you, Kali, for such a great reading of The Sex Obsession and to the Revealer for hosting this interview. You’re exactly right that this book was built through collaborations and relationships that go back a while now. I was trained in religious ethics and one of the prominent methods in the field is the study of practicing communities: How do people realize their ethical commitments in practice? What can we learn about ethical commitments by learning what people actually do? This method calls out for collaboration. I’ve been part of a range of interdisciplinary collaborative projects, including co-writing and co-editing (with Ann Pellegrini most often, and also with Elizabeth Castelli on religion and violence, historian Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy and sociologist Elizabeth Bernstein, and now with Christina Crosby on disability and care). And, particularly through my work at the Barnard Center for Research on Women, I pursued this method by collaborating with activists and artists who were not just organizing for social justice, but also creating new knowledge, developing and elaborating paradigms for undertaking organizing and for social analysis — as Amber Hollibaugh, Catherine Sameh and I wrote for one project, knowledge can be part of “changing how change is made.”

One source of knowledge is actually anger. For example, anger can be an indicator of a moral intuition that something is not right or needs to change. My own approach in allowing anger to animate some parts of the book — which you so rightly recognize — is formed both by the movements I participated in and by feminist scholarship, such as Audre Lorde’s famous essay “The Uses of Anger,” which I read in her important essay collection, Sister Outsider, and which was powerfully influential in both organizing and scholarship. For me, an approach that values the uses of anger in movement work is always in relation to what might be called “joy in struggle.” Two of the movements that were highly influential in my life were my work with the Washington Office on Africa shortly after college in the 1980s when the Office was focused on anti-apartheid work, and then AIDS organizing when I was in graduate school — my lover at the time worked for a Community AIDS Network. It’s more than I can discuss at length here, but both of these movements were dealing with truly exigent circumstances, and yet there was some real joy in the work — and they both had some really, really good parties. That sensibility, combining a willingness to take on powerful forces of injustice, to “act up” with a sense of fabulousness — what Lisa Duggan has called, “the fun and the fury” — is central to my approach.

Your question about anger also brings to the fore the main public actors on whom I focus my critique. The Sex Obsession is an argument about how often gender and sexuality are invoked in political commentary and policymaking, and how frequently sex goes unnoticed — or if noticed, unremarked. So I’m challenging what passes as common sense in the U.S. The book is not focused on actors from what is often called the “religious right” (which for most commentators means specifically the “Christian right,” allowing the category of “religion” to slip into Christianity alone). I focus instead on mainstream and often liberal public discourse, not because the right wing is not part of the story, but because that part has been told and told well, including by Jeff Sharlet, formerly of the Revealer, who, for example, offered one of the few reports on Trump’s June rally in Tulsa that focused on the depth and breadth of his appeal to white Christian nationalism. But these rightwing commitments are certainly not the whole story, and the focus on the right and on the Christian right alone can also contribute to the idea that there is a liberal, secular culture in which the issues tied to the Christian right — racism, xenophobia, obsession with sexual politics — are utterly separate from the predominant secular culture of the United States. I’m not arguing that rightwing politics in the U.S. are not a problem, but rather that, in fact, rightwing politics might be more of a problem than is generally admitted precisely because liberal secular culture shares much of the common sense from which it wants to see itself as separate. Much like white Northerners who were able to understand themselves as separate from racism in the United States by focusing only on the South, liberal secularists like those I write about in the book want to distinguish themselves from racism, sexism, and Christian nationalism, even as they articulate positions dependent on the same underlying narratives.

The contribution of The Sex Obsession is to track the common sense of American politics, a common sense that is all too often shared by both mainstream liberal culture and rightwing culture and, in promoting those shared narratives, liberal discourse can help make it easier for rightwing culture to sustain itself. Some aspect of this shared common sense is the subject of each chapter: the idea that religion is the source of the sex obsession in American politics in the Introduction; the idea that religion and secularism are separate (rather than intertwined) in the first chapter; the idea that morality and materiality are separate or can be separated (rather than intertwined); the idea that the two major political parties in the U.S. are divided over sexual politics (when, in fact, Democratic and Republican ideas about sexual politics are shared on many issues, including material issues like economics); and the idea that the U.S. is a country of exceptional social progress in which democracy expands, instead of a country in which there may be mobility, but that mobility works to reinforce stasis as hierarchies persist.

And then, as you note, the book has been published in the midst of this very strange year, in which we see an intensification of many of the hierarchies the book talks about, particularly through the ways in which stark inequities, including in access to medical care, have meant that the coronavirus has differentially affected people of color. This is happening at the same time that racist police violence is once again at the fore. And the activist researchers at BCRW have been doing really important work on this issue, particularly through the “Interrupting Criminalization Project: Research in Action,” led by Mariame Kaba, with her work on prison abolition, and Andrea Ritchie, who published the important book Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color. This summer has also emphasized the intensification of climate change and its effects, with both hurricanes and wild fires. And we’ve also seen the crystallization of movements to address these injustices, including the Movement for Black Lives.

One of the things the book tries to do is hold together the possible simultaneity of great discouragement with great hope, what I end up focusing on in the conclusion as “melancholy utopias.” Certainly there is much reason for despair right now, but there have also been these incredible glimmers of utopian possibility, such as the truly historic march for Black Trans Lives that brought out into the streets some 15,000 people in Brooklyn in June.

KH: If there was one line from your book I could emblazon on billboards across the think-piece-o-sphere, it would be: “Simply pointing out incoherence will not unravel the fabric.” We seem to put so much hope in pointing out, for instance, that poor people are voting against their material interests; or that there’s no such thing as being “fiscally conservative but socially progressive”; or that “Trump is a bad Christian because he’s a thrice married adulterer.” Then we hold our breath while we wait for the poor, the billionaire “progressives,” and the “good Christians” to rally together on the right side of history and when they don’t, we blame their willful false consciousness rather than considering that maybe the contradictions make (at least historical) sense. Which is my long-winded, frustrated, but grateful, way of asking, can you walk us through the concept of “productive incoherence” and how you use it in your analysis?

JJ: The assumption of coherence in social analysis, which often leads to a need to actively create such coherence, is particularly powerful and has important effects. We’ve seen these effects over the last few years as journalists often produce coherence out of the President’s incoherent statements: “what he seems to be saying is…” “what he might have meant…” “there’s not a plan, but the closest thing to a plan is…” These are just some standard practices as journalists try to explain what’s happening to their readers, but lately people have also been realizing that this effort can contribute to a failure to report the full extent of the incoherence of the administration. Social analysts, like me, often do something similar, where we produce coherence out of incoherence, and it can have similar effects. The drive toward coherence in social analysis reinforces habits of thought that tend to support already dominant narratives, particularly when those narratives also support dominant social relations and attendant hierarchies. What these habits of thought do is coordinate knowledge into already powerful narratives, so that counter evidence (or even just evidence of incoherence) is pushed aside. These habits of thought, thus, make it much harder to break through established narratives and attend to the complexity of social relations. As I argue in the book, incoherence needs to be reported because it is a political tool, and it is one that the current president deploys to great effect — it is a “productive incoherence.” If we could accept that incoherence can be a productive tactic of power, we could analyze and report on that, which is what I try to do.

How does it work that some conservative Christians are so deeply committed to a “thrice married adulterer” and the public articulation of that commitment is often specifically about sexual politics — about things like a conservative judiciary and restrictions on reproductive justice and cutting back on trans rights. Taking this incoherence seriously, rather than just attributing it to “false consciousness,” for example, can have important explanatory power. First, it’s important to say that this disjunction or incoherence is not new — the political avatar of “family values” from the 1990s, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich is also a thrice married adulterer. Second, it is important to move away from personal hypocrisy as an adequate explanation. There may be a lot of hypocritical family-values politicians and public figures, but the repetition of the hypocrisy, even as those who are hypocritical often retain both their political power and their non-monogamous sexual practices, shows that hypocrisy cannot be all that’s at play. Rather, I argue that what’s happening is a commitment not to a personal sexual ethics, but to a nationalist Christian sexual politics. Political scientists Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry argue that Christian nationalism is not just about religious belief, it can also be a form of secular politics. And, similarly, Christian nationalism can be a form of sexual politics — so the commitment is not to political leaders having a personal sexual ethics, but to policies on gender and sexuality that contribute to the constellation reinforcing nationalism. In the second chapter of the book, I synthesize histories of the 1970s to show how this constellation, which involves a range of issues — sexual politics, racial politics, Christian nationalism, anti-communism, and post-industrial economics — came together in the form that is still powerful today.

KH: I’d love to have you summarize the main argument of the book for us, and wondered if you might focus on how you ground the main subjects — common sense, values, and materiality — in the histories and discourses of Christianity, secularism, and Christian Secularism. Or, in other words, can you tell us what role religion has played in shaping American common sense ideas about sex?

JJ: One of the counter-intuitive arguments in the book is that secular freedom is as important as religious conservatism to sexual regulation in the United States. This claim is built on the work that I did with Ann Pellegrini in Love the Sin and Secularisms, in which we lay out the ways in which religion and secularism are intertwined, and, thus, religious regulation and secular freedom are intertwined as well. The common sense in American politics supports both the idea that the United States is an exceptionally religious country — a Christian nation — as embodied by a conservative sexual ethic and also a global beacon of secular freedom as embodied by exceptional equity with respect to gender and sexuality. It’s not just that these two views of the essence of American politics are part of the same commonsense political discourse; they can easily be held and espoused by the same person. So, for example, George W. Bush maintained both that there should be an amendment to the U.S. Constitution banning gay marriage and that one of the reasons the U.S. was morally obligated to go to war in Afghanistan in 2001 was to save or even liberate women who were oppressed by the government of the Taliban. These two positions, religious regulation and secular freedom, are tied together through the underlying common sense, which Ann and I call “Christian secularism.” And we see the effects of this common sense continue in the current moment as the Trump Administration supports a negotiating process that is supposed to create peace in the long-running war in Afghanistan with little regard for its effects on women, even as the current administration also used the same trope of “saving women” in referring to honor crimes as part of the justification for its travel ban against mostly majority-Muslim countries; and the administration has invoked similar ideas about saving women in relation to the administration’s persistent hostility toward Iran. The incoherence between the idea of the U.S. as a Christian nation and also a beacon of secular freedom is sustained and made productive for holding gender and sexual hierarchies in place by holding them apart as separate issues and rarely tracking them together. In other words, the intertwining of religion and secularism produces an oscillation between political invocations of religious regulation and secular freedom as in Bush’s proclamations in one place about same-sex marriage and in another about women’s liberation.

Oscillation between supposedly opposing, but actually intertwined, positions is one mechanism of what I call “mobility-for-stasis.” Another is to move among issues, so as to reinforce common sense political narratives that sustain the status quo. This mobility is characteristic of the liberal commentary that you mentioned at the start of this interview, as liberals argue over whether voters in 2016 were driven more by “economic anxiety” or by “identity politics.” The data now available show that both were active and are, in fact, intertwined in the larger constellation of issues that drive the base of the current Republican Party. Nonetheless, political commentary repeatedly returns to the idea that a single issue — whatever it might be in the moment — is the key. Movement among these issues sets up a situation in which apparent coherence depends on recognizing only one issue as the motive power, while others remain operative, sometimes powerfully, while being shifted to the background. For example, one can claim to be focusing only on economic issues while actually using identity politics in the form of racism and sexism to reinforce existing power relations. For example, when Bill Clinton campaigned for the Presidency with the slogan, “It’s the economy, stupid,” while also banking on racist and sexist tropes about welfare recipients to support his economic policy of “ending welfare as we know it.”

Oscillation between supposedly opposing, but actually intertwined, positions is one mechanism of what I call “mobility-for-stasis.” Another is to move among issues, so as to reinforce common sense political narratives that sustain the status quo. This mobility is characteristic of the liberal commentary that you mentioned at the start of this interview, as liberals argue over whether voters in 2016 were driven more by “economic anxiety” or by “identity politics.” The data now available show that both were active and are, in fact, intertwined in the larger constellation of issues that drive the base of the current Republican Party. Nonetheless, political commentary repeatedly returns to the idea that a single issue — whatever it might be in the moment — is the key. Movement among these issues sets up a situation in which apparent coherence depends on recognizing only one issue as the motive power, while others remain operative, sometimes powerfully, while being shifted to the background. For example, one can claim to be focusing only on economic issues while actually using identity politics in the form of racism and sexism to reinforce existing power relations. For example, when Bill Clinton campaigned for the Presidency with the slogan, “It’s the economy, stupid,” while also banking on racist and sexist tropes about welfare recipients to support his economic policy of “ending welfare as we know it.”

I also look at a series of recent Supreme Court cases to demonstrate how issues move around each other in kaleidoscopic patterns. I contrast this kaleidoscopic movement and the stability it provides for social hierarchies with one of the major narratives of American politics, the assumption of historical progress in which democracy expands by way of stepping stones along the singular path of progress. So, the history of U.S. Supreme Court is often narrated as the institutional foundation of American progress in which the rights of one group after another are recognized. Another way to read this history, though, is that rights are recognized in kaleidoscopic patterns that may bring one or another issue to the fore — front and center in the pattern — but in which the other constitutional rights can then be returned to the background, never staying at the forefront long enough to be fully realized in action. Full equality is never accomplished and groups have to return to reclaim their rights over and over again. I look, for example, at 2013 cases that announced advances in LGBTQ rights in the same week as Shelby County v. Holder was announced as setting back the Voting Rights Act. Why a country dedicated to democracy and equality would need the Voting Rights Act passed in the 1960s, or would again be litigating Voting Rights in 2013 remains unasked. All the while, active, coordinated voter suppression is the great political game of 2020. The need to constantly return to these questions leads to a critique of the progress narrative and identifies the need to address persistent injustice. I suggest this can be done through kaleidoscopic analysis and action (which we can talk more about below).

KH: I really liked your use of the idiomatic “Because X” formulation to structure and link the chapters of the book: 1) Why Sex? 2) Because Religion 3) Because Morality, Because Materiality, 3) Because the Social, 4) Because Stasis. I remember reading an essay a few years ago that was written entirely in this form that I thought was funny, so I posted it on Facebook, and then my high school English teacher commented on it, saying something to the effect of “this person is a terrible writer” — entirely missing the joke. It was a very “okay, boomer” moment, avant la lettre. Which is all to say, what made you decide to use the formulation as part of the scaffolding for your book?

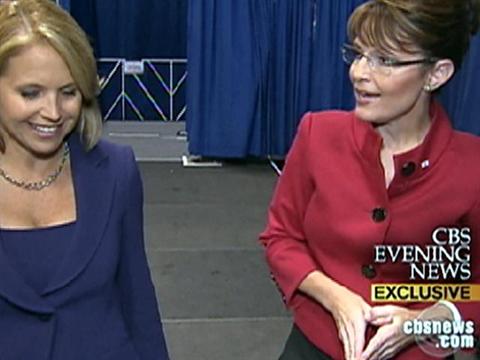

JJ: So, having gotten a little of the fury out of the way, we can turn to some of the fun. First, “Because reasons” may be something of an “OK, Boomer” response (and I must admit to being a “boomer” — I was born in 1960), but I am charmed by the formulation, nonetheless. “Because reasons” seems like an all too appropriate summary of political discourse in which political leaders so often offer explanations for their actions that are really just lists, no matter the relevance or lack thereof, or in some cases no matter the utter lack of a factual basis for the claims. Why are so many really questionable things happening in political life? Because reasons. I’m also charmed by the popular connection of “because reasons” to the internet’s summary of Sarah Palin’s response when Katie Couric asked her to name the news publications she reads, “All of them, Katie.” Which reasons? All of them, Katie.

Katie Couric interviewing Sarah Palin in 2008

That said, I do live with an English Professor, Christina Crosby, and write with Ann Pellegrini, whose grammatical precision I find dazzling. So, embracing a grammatical error for my chapter titles was also a way (a fun way, admittedly) of highlighting the book’s argument that common sense is often reproduced by social analysis that is structured by the obverse of “all of them, Katie.” As we saw in the mobility-for-stasis examples above, social analyses often strive to find a single “reason” for any social phenomenon. In the case of the sex obsession, the answer would be something like: American politics is obsessed with gender and sex because of the Puritan heritage of the United States. Single variable, single cause, definable cause. I contrast this answer to the “why sex?” question, in part with help from historians of both sexuality and religion who show that Puritan heritage is not singularly explanatory of American politics. For example, it erases the indigenous peoples who were here when the Puritans arrived as well as overplaying their historical role. Nor can sexual politics be reduced to religious influence; one chapter traces the investments in sexual politics of secular policy-making across both Democratic and Republican administrations. And, once the analysis lets go of the single, Puritan explanation, there is so much to discuss that it takes the rest of the book. At one point I say, “Why sex? Because religion. Because sex. Because everything.”

I understand the desire to find that single answer that could provide a direct way of addressing various social problems, but I argue that it’s simply inadequate. In the chapter that really focuses on this epistemological question, I briefly look at one good faith effort at putting this kind of single variable social analysis into practice by a prosecutor in Wisconsin who wanted to address racial disparities in imprisonment and who worked with the Vera Center on a study that showed that the single most important variable in racial differential in sentencing was prosecutorial discretion. So, the prosecutor did a number of things to try to change practices and it did change discretionary actions of his office, but it had only a minor effect on differential imprisonment. The system was too complex for any single reform to make that significant of a difference. Black feminists have addressed some of the problems with this single variable approach through the concept of intersectionality, and I follow this strategy by taking a dynamically intersectional approach. I end up using the metaphor of a kaleidoscope in which not only do a number of different issues come together, they are also in motion in relation to each other. The chapters move kaleidoscopically among different answers that might be offered to the question of sex in public discourse, starting with religion, but then turning to ethics and economics, because religion is often taken to simply be a “symbolic” cover for more material economic concerns, and then moving on to sex and the social, and the way in which the single line of social progress is supposed to solve all problems.

KH: I want to think with you about the ways that sex is not just the object of your analysis but is, in fact, embedded in the conceptual framing of your argument. For instance, you model (and call for more) “theoretical promiscuity” and for “perverse justice.” I wonder if you could tell us more about what theoretical promiscuity means and, specifically, how your engagements (liaisons?) with religious studies have shaped your thinking?

JJ: This is a really perceptive question. At the end of Love the Sin, Ann and I say that sex is a source of values. Such a claim seems completely counter-intuitive in current public discourse, where sex is taken to be opposed to values or needs to be controlled by values — or values voters. But sex is a material practice around which many people create what they value in life and in relation to which they organize much of their lives, whether familial lives, or religious lives committed to celibacy, or queer lives, or single lives, or some other form. Sex also makes connections among people which can be crucially important. The example we use in Love the Sin is that of the type of mutual aid developed in queer communities in response to the AIDS crisis.

I also think that sex is a source of knowledge. My book appears in NYU Press’s “Sexual Cultures” series, and my thinking has been formed by the idea that there are sexual cultures and that sex produces knowledge. If, as I mentioned at the beginning, knowledge is produced through practice, then sexual practice would produce certain forms of knowledge. So, in the current pandemic a set of questions about mutual aid and caring for each other have once again come to the fore, and the learning offered by the sexual culture that enabled mutual aid in response to AIDS can be helpful, as can a set of queer practices, in which, for example, people form social units that are not familial or extend beyond the familial, which in the pandemic are becoming pods, or quarenteams, or the like.

So, central concepts, like “theoretical promiscuity” and “perverse justice” are, in fact, grounded in sexual cultures. First, both concepts draw on a sense of non-normativity — whether gender or sexual non-normativity, or as I argue at one point, religious non-normativity in the midst of a predominantly secular politics. The world is complicated. Not everything fits together. Not all religions are particular instances of a general category called “religion,” and not all gendered lives conform to gendered categories (no matter how many such categories Facebook tries to produce). Theoretical promiscuity acknowledges that no single theory or framework is going to be adequate to the complexity of the world. In fact, one of the main reasons for the metaphor of the kaleidoscope is to try to move away from the metaphor of a framework as adequate to the complexity of the world. The world is dynamic and may look one way from one perspective and another way from a different perspective. One of the many important points about intersectionality is that it moves away from an “additive” approach to different perspectives on social analysis. So, unlike the metaphor of people trying to describe a phenomenon from different perspectives even though they cannot see the whole where the perspectives must be added together, one must also account for that which doesn’t just “add up,” which is, for example, both simultaneous and disjunctive. Similarly, with “perverse justice,” I am interested in building forms of justice that don’t imagine that everything can be justified or accounted for, forms which do not try to create or restore a holistic version of social relations, but which instead attend to grief and loss, even as they contribute to transformative responses and potentially joyful relations.

KH: Let’s talk about kaleidoscopes and reading and thinking kaleidoscopically. To me, it seems, you offer the kaleidoscope to your reader for two kinds of uses: first, as a way of organizing an understanding of history and politics — these are the actors, these are their interests, these are the kinds of power at play — so that we can see how they twist and turn, combine and recombine, shifting together over time and across issues. And second, as a way to think and critique these histories, these configurations of power, to try and twist them and refocus them and ourselves. It might be a bit too precious, but as I was reading, I was thinking of the little kaleidoscope toys I had as a child, full of beads and glitter and such, and how, if you pointed them at the light the right way, you were rewarded with a tube full of shimmering rainbow fragments. Not to totally femme up your metaphor, but I was seduced by the idea that if we used a kaleidoscope to read history, to read the news, we could flood it with useful distortions, with glitter and rainbows. Can you tell us how you came to this metaphor and how you envision it being used further?

JJ: My initial response to this question was simply to write: Glitter is important — it is politically important.

It’s tempting to leave that response there for those who enjoy a femme sensibility in which sharing glitter with the world is part of making justice. But you’ve also given me an opportunity to talk a little more about what kaleidoscopic action might mean. As you point out, one of the projects of my book was to find another metaphor that might help to envision dynamic and potentially disjunctive social relations. I turn away from the idea of a framework as an epistemological metaphor and toward the idea of a kaleidoscope so as to articulate how multiple distinct aspects of social relations might come together to form patterns that are themselves changeable. And articulations across these patterns can be created if we as analysts are willing to attend to the multiplicity, variation, and gaps, in which not all pieces appear in all patterns or are always the same size. Hence, my idea of being able to build a universal from the multiple, incoherent realities in which people experience their everyday lives. It is somewhat akin to a Rawlsian idea of an overlapping consensus, but eschews the idea that these articulations necessarily overlap or lead to consensus — they may just be understandings across difference. Understanding need not be built on overlap. I appreciate the points at which people find unexpected overlap. I turn, for example, to Alison Kafer’s important reading of the ways in which trans activism and disability activism overlap around the role of bathrooms in public life. And, I am also interested in issues where overlap is harder to find, where connections need to be built or solidarity created. Most of all, I want to resist the sense that every phenomenon can be made to fit some coherent whole, because that is one of the ways people who are already marginalized, including queer, trans, and disabled people disappear from social analysis. Kaleidoscopic action allows for a dynamic sense of where people might find or even build connections — across communities, across issues, across intellectual, political, and religious traditions.

It’s tempting to leave that response there for those who enjoy a femme sensibility in which sharing glitter with the world is part of making justice. But you’ve also given me an opportunity to talk a little more about what kaleidoscopic action might mean. As you point out, one of the projects of my book was to find another metaphor that might help to envision dynamic and potentially disjunctive social relations. I turn away from the idea of a framework as an epistemological metaphor and toward the idea of a kaleidoscope so as to articulate how multiple distinct aspects of social relations might come together to form patterns that are themselves changeable. And articulations across these patterns can be created if we as analysts are willing to attend to the multiplicity, variation, and gaps, in which not all pieces appear in all patterns or are always the same size. Hence, my idea of being able to build a universal from the multiple, incoherent realities in which people experience their everyday lives. It is somewhat akin to a Rawlsian idea of an overlapping consensus, but eschews the idea that these articulations necessarily overlap or lead to consensus — they may just be understandings across difference. Understanding need not be built on overlap. I appreciate the points at which people find unexpected overlap. I turn, for example, to Alison Kafer’s important reading of the ways in which trans activism and disability activism overlap around the role of bathrooms in public life. And, I am also interested in issues where overlap is harder to find, where connections need to be built or solidarity created. Most of all, I want to resist the sense that every phenomenon can be made to fit some coherent whole, because that is one of the ways people who are already marginalized, including queer, trans, and disabled people disappear from social analysis. Kaleidoscopic action allows for a dynamic sense of where people might find or even build connections — across communities, across issues, across intellectual, political, and religious traditions.

Kaleidoscopic action also allows for an appreciation of the relation between beauty, joy, and justice. I’ve talked some about the activists who work with BCRW and I’ve also had the chance to collaborate with artists who turn beauty into justice and justice into joy. Right now, for example, I’m working with Pamela Phillips at BCRW on a project called, “Changing the Narrative: A Public Housing Project.” It involves gathering community stories of people’s lives in New York public housing, so the housing residents interview each other about what they value. That project has also connected to a dance project with Sydnie Mosley, who leads Sydnie L. Mosley Dances and is a community engagement fellow at Lincoln Center. We held a workshop in which Sydnie translated stories from the senior center of Amsterdam Houses near Lincoln Center into a dance called “Purple.” Amsterdam Houses was created after New York City wrecked the existing neighborhoods around Lincoln Center for the sake of “urban renewal,” and many people lost their homes and had to relocate. “Purple” asks what kind of beauty can be made by embodying people’s stories of living on in the face of this kind of structural violence. Making art can be one way of documenting violence while refusing to accept a world without beauty. If my book can contribute to the sense that glitter is good — and perhaps even powerful — in the face of injustice, then I would be very happy. “Glitter Not Greed” is a fine summary of the book. So thank you for that reading.

KH: This all leads, for me, to what I found to be one of the most challenging parts of the book, which was your argument about universalism. The religious studies theory and methods canon today is a kind of (ironically) progressivist trip through history from 19th century universalism through to 1990s critiques of universalism — from Emile Durkheim to Talal Asad, basically. But you suggest that, in fact, “universal claims also allow for a vision of the world that creates possibilities for surviving and even thriving regardless of the prevailing hegemonic logic” that would help us build a “utopian, but melancholy, project of universal claims like ‘“no one is disposable.”’ Then, especially interestingly given the kind of religious studies theories and methods syllabus I just recited, you go on to say that, “The idea that a different type of universalism might be possible comes from a number of different sources, bringing together the religious studies critique of secularism with the queer critique of normativity.” So, I wanted to ask more about this kind of universalist thinking. How would you define it and what do you hope for from it?

JJ: With respect to universalism, I basically agree with your genealogy of the field, from 19th century understandings of religion to the work of Talal Asad. This trajectory sees the field beginning from understanding religion as a particular social phenomenon within the universal (or soon to be universal) field of liberal secularism. As secularization proceeded, religion would be increasingly moved from the public sphere to a private matter or even fade away as more and more of the world accepted secularism as the framework of their lives and thus, secularism would be(come) universal. But, of course, the predicted uninterrupted path to secularization led to some bumps and roadblocks, particularly when the political import of religion became apparent in mainstream media and scholarship with both political Islam and the Iranian Revolution and conservative Christianity in the United States. The field then moved more toward a critique of secularism and of the categories of both religion and secularism. My question now is along the lines of: where does the field go from that point of critique? And, in answer, I take up the idea of a universalism that is built “from the ground up” in the conclusion of the book.

The idea of universalism that I turn to is not by any means a liberal or necessarily secular universalism — the book has a couple of projects related to this: first, I take up historian Anne Braude’s exhortation to find religion in unexpected places, including, of course, in various forms of activism for social justice, such as the inter-faith network of centers for workers whose jobs are not the focus of traditional labor organizing, or the type of support for asylum seekers that David Seitz documents in his book A House of Prayer for All People. Second, I am interested in what Melissa Wilcox points to as practices that are neither precisely religious or precisely secular, a move that is reflected not only in the practices of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence that Melissa tracks, but also in the kind of queer secular-religious ecstatic community that José Esteban Muñoz convokes in Cruising Utopia. Refusing to stick with the religion-secular binary or even the categories as we know them is one step/practice toward shifting these categories from their colonial meanings. Instead of a liberal universalism, I appeal to an idea of the universal that is multiple, fragmentary, aspirational, melancholy, contradictory, and built rather than found.

This conceptualization is built in part through my living with practices of universal access and universal design from disability studies and activism. In particular, there is no paradigmatic disabled person, so the idea of universal design immediately undercuts a liberal, secular idea of a normative universal human. And, in fact, many changes to the organization of the social world and built environment that might be helpful to one disabled person could make life harder for someone else. So, you can begin to get the idea of how universal design is fragmentary and contradictory and how creating a universal that encompasses everyone is — and will remain — an aspiration that cannot be achieved in practice. Hence, the melancholy. These challenges have led some disability activists to move away from the concept, but instead I move to embrace the conceptual complexity. I do this, in part, because the activists I work with continue to make universal claims and those claims are powerful. So, I think with the prison abolitionist claim made by trans activists, Tourmaline, and Dean Spade that “No one is disposable.”

This is a powerful claim and not one I would want to give up. For someone to be disposable is to my mind morally unacceptable. This activist claim, then, incites a rethinking of what a universal might be. And, indeed, religious studies, is helpful here, because religious people also often make universal claims. But the universal claims that ground different religious practices and different religious ethics are not all the same type of claim. As you might expect from my frequent refusal of coherence, I also refuse to put these different kinds of claims into either a single category or framework. As I have written elsewhere, religious universals are often treated as particular universals versus the universal universal of secularism. In my first book, Working Alliances and the Politics of Difference, and in various essays I have made an effort to show how (as with so much else) the claim to adjudicate among different types of universal claims, including religious claims, within a single secular framework tends to reiterate the hierarchies and exclusions that are the infrastructure of injustice — of the very injustice that secularism is supposed to resolve.

KH: Your book is written so clearly, and so compellingly, it made me itch to teach with it. That itch was particularly strong when I thought about the complaint students often levy against theory and critique, that our post-modern histories of social construction and discourse can make us feel stuck, unable to act in ways that affect real change. Sometimes I’m sympathetic to this frustration, at others it feels disingenuously unimaginative and ungenerous. But your book manages to be both theoretically and critically rich and is also explicitly prescriptive. You use your own work and the work of your comrades and collaborators to think toward new and better ways of doing the work of thinking and organizing — for “changing the conversation” and more. You write, “Developing new ways of being in the world requires new ways of thinking about and understanding that world. I am animated by the hopefulness of a perversely utopian justice that does not secure its borders, while I understand that universal inclusiveness can never be achieved. The question for activists is how to stick with enabling paradoxes like this one.” I was very taken with this idea of “perverse utopian justice.” Perversity, especially, seems like such a rich word — in terms of sex, in terms of religion — to hook into here. Can you tell us more about what “perversity” means to you, to this work, to this kind of utopian thinking and organizing? How might perversity help us feel less stuck?

JJ: I really cannot do justice to perversity. And this is for the reason that you say — perversity is rich with possibility.

One of the basic ethical questions for me is how to make a world that is different from what exists right now, pervaded as that world is by injustice. I turn to the slogan from the World Social Forum and the Occupy movement, “Another World is Possible.” It’s such an expansive, hopeful slogan. But how is another world possible? One of the things I’ve learned from my years of research is that those of us who start out trying to make another world, a different world, often end up, as I said in my first book, “reproducing the same.” Social movements can contribute to mobility-for-stasis. Social movements can build a future that is laid out by the past and all of its violence, rather than one that answers that violence. So, how does ethical action remain open to the world without avoiding, ignoring, or denying either its complexity or violence? One approach is not to stick to the future offered by the past, nor deny the material power and constraint of what has happened historically. Rather than denying history and its power, one can instead pervert its straight and narrow path.

One of the basic ethical questions for me is how to make a world that is different from what exists right now, pervaded as that world is by injustice. I turn to the slogan from the World Social Forum and the Occupy movement, “Another World is Possible.” It’s such an expansive, hopeful slogan. But how is another world possible? One of the things I’ve learned from my years of research is that those of us who start out trying to make another world, a different world, often end up, as I said in my first book, “reproducing the same.” Social movements can contribute to mobility-for-stasis. Social movements can build a future that is laid out by the past and all of its violence, rather than one that answers that violence. So, how does ethical action remain open to the world without avoiding, ignoring, or denying either its complexity or violence? One approach is not to stick to the future offered by the past, nor deny the material power and constraint of what has happened historically. Rather than denying history and its power, one can instead pervert its straight and narrow path.

This turning of the material world (and of materialism) toward possibility is for me an enabling paradox. How, for example, can we aspire to utopian possibility while recognizing the grief of living? I suggest that we can take up the somewhat perverse idea of a melancholy utopia, or of fun and fury, or of justice and joy, or of glitter as central to social analysis. Such is the perversity and possibility of both ethics and politics.

Kali Handelman is an academic editor based in London. She is also the Manager of Program Development and London Regional Director at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research and a contributing editor at the Revealer.

Janet Jakobsen is Claire Tow Professor of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Barnard College, Columbia University and author of the newly published, The Sex Obsession: Perversity and Possibility in American Politics and co-author with Ann Pellegrini of Love the Sin: Sexual Regulation and the Limits of Religious Tolerance.