Race, Religion, and the Indian-American Vote

Indian-Americans are a crucial demographic in this election, and their voting patterns could be changing

Vice President Joe Biden greets Indian Ambassador Nirupama Rao in 2012. (Photo: David Lienemann)

Of the 4 million Indian-Americans living in the United States, approximately 2.5 million are eligible to vote in the upcoming presidential election. 1.3 million of those reside in eight key battleground states: Florida, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Arizona, Georgia, Texas, and North Carolina. Considering that some of those states were won or lost by a few thousand votes in 2016, both Democrats and Republicans are paying increasing attention to this demographic.

Indian-Americans are among the most well-educated and wealthiest ethnic groups in the United States. According to the Pew Research Center, as of 2015 52% had either a bachelor’s or post-graduate degree and their median household income was $100,000. Compare that to the national averages of about 30% and $60,000, respectively. Indian-Americans own a third of all Silicon Valley start-ups and lead 2% of American-origin Fortune 500 companies including Microsoft, IBM, and Alphabet. Yet caste, class, and religious divides heavily shape Indian-Americans’ access to both educational and economic resources. About half are Hindu, 18% Christian, 10% Muslim, 5% Sikh, and 2% Jain. Caste discrimination is an issue faced by many Indian-Americans – a reality confirmed by data collected by the Equality Lab in 2018, and by the recent lawsuit against Cisco in California in which an engineer alleges that he faced discrimination from two upper-caste supervisors.

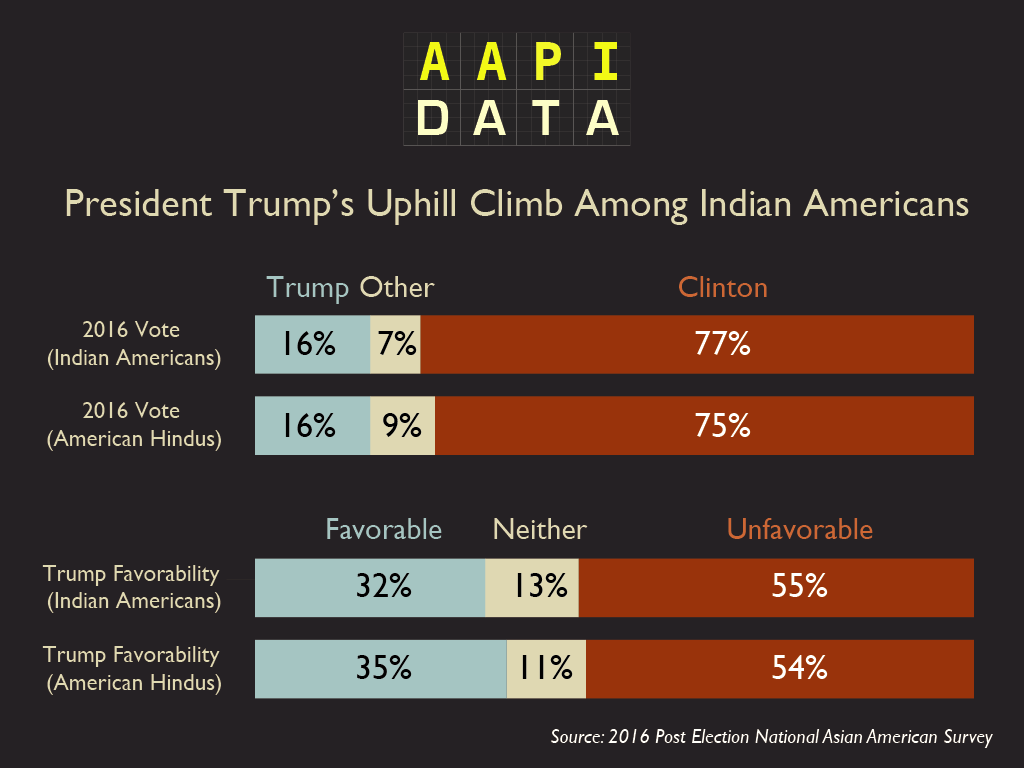

In previous elections Indian-Americans have leaned left, with 77% voting for Clinton in 2016 and only 16% for Trump. But Indian-American support for the Republican Party, and Trump specifically, is growing. Al Mason has made the claim on a conservative media outlet that 50% of Indian-Americans living in swing states are shifting their support this year in favor of Trump. He does not substantiate this claim, and yet the potential for Indian-American voters to change allegiances in this election is one that is energizing both parties.

Over the past few months, both campaigns have launched ads aimed at capturing the Indian-American vote. The Trump ad features the president and India’s prime minister Narendra Modi walking hand-in-hand before roaring crowds of thousands in Houston and Ahmedabad for the “Howdy Modi” and “Namaste Trump” events. Biden’s ad features Indian-American voters pledging their support for him in multiple Indian languages. Biden also chose Kamala Harris – daughter of an Indian mother and Jamaican father whose name means “lotus flower” in Sanskrit – as his running mate.

Over the past few months, both campaigns have launched ads aimed at capturing the Indian-American vote. The Trump ad features the president and India’s prime minister Narendra Modi walking hand-in-hand before roaring crowds of thousands in Houston and Ahmedabad for the “Howdy Modi” and “Namaste Trump” events. Biden’s ad features Indian-American voters pledging their support for him in multiple Indian languages. Biden also chose Kamala Harris – daughter of an Indian mother and Jamaican father whose name means “lotus flower” in Sanskrit – as his running mate.

‘From Lotus to POTUS’?

When Biden selected Harris as his running mate, Indian and Indian-American news media exploded with variations of the above headline, but without the qualifying question mark. Indian pundits started to ponder the potential benefits of her candidacy for India, while Indian-Americans celebrated the arrival of one of their own on the political scene – a hard fought battle in a nation where aspiring Asian politicians have for so long been read as “foreign,” no matter their country of origin. Various outlets have covered Harris’ Indian background as central to her upbringing, values, and dedication to democratic ideals (India is the world’s largest democracy). Her maternal grandfather worked for the Indian government and her parents met at Berkeley during the 1960s where they were both involved in the Civil Rights Movement. While Harris is a member of a Baptist Church, Hinduism was an important part of her upbringing. The New York Times reported that she asked her aunt in Chennai to complete a Hindu ritual in which 108 coconuts are broken for good luck in her race for California Attorney General. Some refer to her middle name “Devi” as further evidence of her Hindu heritage.

Harris with her mother in 2007

The official website for the Biden-Harris campaign outlines an “Agenda for the Indian American community” that includes many democratic platform issues, including rebuilding America’s middle class, ensuring access to health care and education, and providing paths for citizenship for illegal immigrants. But first and foremost, they pledge to stem the tide of hate and bigotry in the United States by focusing resources to combat hate crimes. Such crimes have increased since Trump’s election in 2016 according to the FBI’s statistics, and they disproportionately affect Black and Brown communities, including those of Indian-Americans. The Biden-Harris campaign promises to focus additional resources to combat hate crimes, increase sentences for hate crimes committed in houses of worship including gurdwaras, mandirs, and mosques, and fund federal security services for houses of worship.

Here are just a few examples of hate crimes reported by the Indian-American community in recent years: In 2012, in one of the deadliest hate crimes in recent history, a white supremacist with ties to neo-Nazi groups opened fire at a Sikh gurdwara in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, killing six people (Paramjit Kaur, Satwant Singh Kaleka, Prakash Singh, Sita Singh, Ranjit Singh, and Suveg Singh Khattra) and wounding another four. In 2017, Srinivas Kuchibhotia was killed and Alok Madasani injured when they were shot at a restaurant in Olate, Kansas, by a man who fired eight rounds after calling the men “terrorists,” and shouting “Get out of my country!” Earlier this year, vandals trashed an Indian restaurant in Santa Fe, graffitiing racist slogans such as “white power,” “go back,” alongside “Trump 2020” across the walls and causing over $100,000 in damages. These are not isolated incidents but part of a much broader trend in which Indian-Americans, be they Hindu, Muslim, or Sikh, alongside Jewish, Latinx, and Black communities, are subject to taunts, bullying, and violence. The impact far outlasts the incidents themselves in the form of fear, isolation, and insecurity. Three days after the Oak Creek massacre, for example, a white man asked a Sikh cab driver in that town to roll down his window, pretended to shoot him, and said “This isn’t over.” Seven days after that, another Sikh man in Oak Creek, Dalbir Singh, was murdered while closing his store. Lawyer and civil rights activist Valarie Kaur remarked, “Like other racial and religious minorities in U.S. history, we are robbed of the opportunity to finish mourning; we must remain ever vigilant, ever waiting for the next act of violence.”

Biden and Harris’ agenda for a strong U.S.-India partnership similarly focuses on human rights, appealing to India and America’s “shared democratic values.” The campaign reminds voters of Biden’s long-standing support for a close relationship between the two nations, encapsulated in Biden’s 2006 statement as incoming Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee when he was working to finalize the India-U.S. nuclear agreement: “My dream is that in 2020, the two closest nations in the world will be India and the United States.”

In their “Agenda for Muslim-American Communities,” Biden and Harris explicitly denounce policies recently enacted by India’s right-wing Hindu nationalist Prime Minister Narendra Modi. These include his recent revocation of Article 370, which removed the autonomous status of Muslim-majority Kashmir while shutting down all communication in the region and placing many dissidents under house arrest. Harris spoke about this directly earlier this year, remarking, “We have to remind the Kashmiris that they are not alone in the world. We are keeping track of the situation. There is a need to intervene if the situation demands.” The Biden-Harris campaign similarly denounces the Modi government’s creation of a National Register of Citizens [NRC] and the implementation of the Citizenship Amendment Act [CAA]. Together, these policies register the citizenship of every Indian and then allow those without birth certificates or other qualifying paperwork (in the eastern state of Assam where this project began, that was 10% of the population) a fast track to citizenship unless they are Muslim. This is the first time India has used religion as a criterion for citizenship in this, the world’s largest democracy. All three of these policies have been assailed by world leaders and human rights activists throughout India and internationally as anti-Muslim and as deeply concerning from a human rights perspective.

Trump Appeal

For the 15-20% of Indian-Americans who have supported the Republican Party in the past, promises of lower taxes and conservative family values hold more sway than the Democrats’ appeals. To the particularly wealthy among them, equality in education and health care reform sound like big government. They oppose paths to citizenship for illegal immigrants because they see themselves as having played by the rules and believe others should do the same. Many among this constituency do not see bigotry and hate crimes as issues requiring systemic change. Indian-American and former Governor of South Carolina Nikki Haley (arguably Harris’ counterpart in the Republican Party as many touted her as a VP pick and, some now speculate, a future presidential candidate) assured viewers at the Republican National Convention in August that “America is not a racist country.” This remark was followed by her admission that she faced difficulties growing up as a Brown girl in the American South. Elsewhere she has spoken about the racism she faced as a Member of the House of Representatives and as Governor of South Carolina. Like many Trump Republicans, she sees these as isolated incidents. Complicating this stance on race is a strand of anti-Black racism that runs through Indian-American communities. It compels some to uphold a “model minority” status by distancing themselves from Black Americans and so-called “Black issues.” This strand also compels some to distance themselves from the Jamaican half of Harris’ lineage.

One might surmise that Trump’s “America first” and anti-immigrant platform would be off-putting to Indian-American voters. And yet, for many, it is one of his most attractive qualities. To understand this, one must first understand something about Indian politics. In India, social divides occur predominantly along lines of religious identity rather than race because of the way its previous colonial rulers classified Indian populations. India’s population breakdown by religion is currently 80% Hindu, 15% Muslim, and 5% other minorities. Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has consistently won national elections since 2014 on a platform of majoritarian politics that appeals to upper-caste and upper-class Hindus as they combat what they see as unfair affirmative action policies (known as the “reservation system”) favoring Muslims as well as low-caste groups, and the immigration of Muslims from neighboring Pakistan and Bangladesh (both part of India until 1947). The above-mentioned NRC, CAA, and revocation of Article 370 are touted by Modi’s supporters as evidence of his strong stance against Muslim incursions in a Hindu nation. Indian-American Trump supporters see the same in their president – a strongman willing to stamp out illegal immigration – especially from neighboring countries and from Muslims in particular. They are convinced by both leaders’ claims that such policies put their country and its citizens first and are effective at combating terrorism.

One might surmise that Trump’s “America first” and anti-immigrant platform would be off-putting to Indian-American voters. And yet, for many, it is one of his most attractive qualities. To understand this, one must first understand something about Indian politics. In India, social divides occur predominantly along lines of religious identity rather than race because of the way its previous colonial rulers classified Indian populations. India’s population breakdown by religion is currently 80% Hindu, 15% Muslim, and 5% other minorities. Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has consistently won national elections since 2014 on a platform of majoritarian politics that appeals to upper-caste and upper-class Hindus as they combat what they see as unfair affirmative action policies (known as the “reservation system”) favoring Muslims as well as low-caste groups, and the immigration of Muslims from neighboring Pakistan and Bangladesh (both part of India until 1947). The above-mentioned NRC, CAA, and revocation of Article 370 are touted by Modi’s supporters as evidence of his strong stance against Muslim incursions in a Hindu nation. Indian-American Trump supporters see the same in their president – a strongman willing to stamp out illegal immigration – especially from neighboring countries and from Muslims in particular. They are convinced by both leaders’ claims that such policies put their country and its citizens first and are effective at combating terrorism.

Trump and Modi have capitalized on their strong-man similarities at two recent events in Houston and Ahmedabad. In what the Washington Post describes as “the largest-ever gathering with a foreign political leader in the United States,” 50,000 people congregated in Houston last September to welcome Narendra Modi in the “Howdy, Modi!” event funded primarily by The Texas India Forum. There, Modi and Trump stood on stage hand-in-hand as Modi justified the revocation of Article 370 in order to ensure “equal rights” to Kashmiri citizens. Modi introduced Trump as “my friend, a friend of India, a great American President,” to loud applause. Trump responded in kind, calling Modi “one of America’s greatest, most devoted, and most loyal friends.” In February of this year, Trump visited Ahmedabad for the “Namaste Trump” event, drawing a crowd of 100,000. There, too, the leaders joined hands before lavishing praise upon one another from the podium. Unlike Biden and Harris, Trump has not criticized Modi’s actions in Kashmir and Assam. Instead, he has extolled their joint “ironclad resolve to defend our citizens from the threat of radical Islamic terrorism.”

Trump and Modi

Indian-American voter Al Mason is explicit about what Trump has to offer Indian-Americans: respect. In his own synopsis of the commercial he created for the Trump campaign, he points to the Modi-Trump events and Trump’s lack of criticism over the Kashmir issue to argue: “Indian-Americans for the first time ever feel respected by the United States. No one has ever respected India, nor the Indian prime minister, nor the vast Indian-American community as much as President Trump has.” He does not cite former U.S. presidents’ numerous state visits to India, including Obama’s visit in 2009 when he met with then-prime minister Manmohan Singh after endorsing the nation’s plea for a permanent seat on the U.N. Security Council, or in 2015 when he met with Modi and became the first U.S. president to participate in Republic Day celebrations, promising to increase bilateral trade between the two nations. It is Trump’s refusal to criticize the Indian prime minister and his policies that counts as respect.

This line of logic doesn’t sit well with other Indian-American voters. Nyla Ali Khan, granddaughter of the first prime minister of Jammu and Kashmir after India gained independence now resides — and votes — in Oklahoma. When the entire Kashmir Valley was put on lockdown after the revocation of Article 370, that included her family members (who are Muslim). Of Indian-American Trump supporters, she remarks: “These transnational subjects are safely ensconced in the U.S. and they remain unaffected by the wreckage caused by Modi’s policies, so they are uncritically loyal to the romanticized notion of the nation.” She warns against Hindutva nationalist groups in the U.S. who are “related to the invention, transmission, and revision of nationalist histories” that, in Kashmir, “justify repression of the Kashmiri populous, objectification of Kashmiri women, and humiliation of the people with the language of affirmative action and good governance.”

Lopamudra Basu, Professor of English and Philosophy at the University of Wisconsin who is Hindu by birth and who identifies as progressive in her politics similarly rejects Mason’s logic: “In spite of the optics of the camaraderie between Trump and Modi, the Trump administration has been devastating to Indians in its policies. It has slapped tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from India and removed India’s status in the GSP (Generalized System of Preferences). In effect, it is conducting a mini trade war with India. Even more significantly, [the] U.S has reduced HI B visas, a category of work visas that Indians rely on in the path to immigration. I am hopeful that these empirical facts weigh more with the Indian-American electorate than a common xenophobia and ethnocentrism.”

2020 and Beyond

Whatever traction Trump gains among Indian-Americans, most will likely continue to hold democratic views and vote for Biden in the 2020 election. Valarie Kaur says the stakes for this election couldn’t be higher. A third-generation Indian-American, she calls on her religious community to remember the historical experience of Sikhs and core values of their tradition: “As Sikhs, we are called to love and serve one another — and fight for those in harm’s way. Right now, millions in this nation are suffering — from pandemic, climate catastrophe, police killings, poverty, and hate violence. Everything our Sikh ancestors fought for — a world of dignity, equality, and justice — is at stake. A Biden presidency would give us a chance to save our democracy, heal the earth, and begin to birth a world where we see no stranger.” Her nonprofit organization, The Revolutionary Love Project, has teamed up with Emgage, a Muslim-American advocacy group, to increase voter participation among MASA (Muslim, Arab, and South Asian) constituents in battleground states.

For Nyla Ali Khan, the stakes are indeed high, and yet this election is one small step in a much larger human rights project. She remarks: “We are witnessing a rise in religious majoritarianism and cultural-supremacist politics the world over, which is why the U.S. presidential election cannot be a stopping place for our thinking about a world radically transformed by struggles for autonomy and self-determination.”

It remains unclear what a Biden-Harris presidency would mean for Kashmir, specifically, or India as a whole, but for these and for most Indian-American voters, it is critical for America’s future.

Deonnie Moodie is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Oklahoma and a Sacred Writes/Revealer Writing Fellow. She is the author of The Making of a Modern Temple and a Hindu City: Kālīghāṭ and Kolkata (Oxford University Press, 2018). She is currently writing a book about the recent emergence of Hindu ideologies in Indian business schools and corporations.

***

This article was made possible in part with support from Sacred Writes, a Henry Luce Foundation-funded project hosted by Northeastern University that promotes public scholarship on religion.