Priests That Moved: Catholicism, Colonized Peoples, and Sex Abuse in the U.S. Southwest

How should we understand the higher rates of clergy sexual abuse in dioceses with large Native American populations?

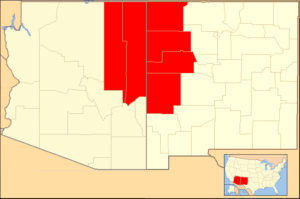

In 1936, Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli reportedly soared in an airplane high over Diné Bikéyah, the lands of the Navajo people. Peering down over the mesas, the man who would become Pope Pius XII “wondered how the scattered Indians in the area would be adequately served.” Three years later, the new pope established a Roman Catholic diocese for this ministry. When it began in 1939, the Diocese of Gallup—the first and only “Indian diocese” in the United States—covered great swaths of western New Mexico and northern Arizona, and reservation lands inhabited by Navajo, Zuni, Hopi, Apache, and other Native nations. Its boundaries contained a Catholic population between thirty and forty thousand that, according to one Church survey, was twenty-seven percent Native, fifty-eight percent “Spanish American” (sometimes also called “Mexican” in Church records), and fifteen percent Anglo.

In 1936, Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli reportedly soared in an airplane high over Diné Bikéyah, the lands of the Navajo people. Peering down over the mesas, the man who would become Pope Pius XII “wondered how the scattered Indians in the area would be adequately served.” Three years later, the new pope established a Roman Catholic diocese for this ministry. When it began in 1939, the Diocese of Gallup—the first and only “Indian diocese” in the United States—covered great swaths of western New Mexico and northern Arizona, and reservation lands inhabited by Navajo, Zuni, Hopi, Apache, and other Native nations. Its boundaries contained a Catholic population between thirty and forty thousand that, according to one Church survey, was twenty-seven percent Native, fifty-eight percent “Spanish American” (sometimes also called “Mexican” in Church records), and fifteen percent Anglo.

The Diocese of Gallup introduced an infrastructure for spiritual care aimed at the region’s mainly Native and Latino inhabitants. Within a year the diocese had its own bishop, Bernard Espelage, and a modest cathedral in the coal- and railroad-fueled bordertown of Gallup, adjacent to the Navajo reservation. In the months and years that followed, the diocese gained its own stable of priests who arrived from as near as Santa Fe and as far as Ireland to work at Bishop Espelage’s direction, in both parishes and outlying mission churches and schools. The new diocesan clergy complimented and sometimes competed with other priests from the Franciscan religious order who were already established at Native-serving missions in the region.

In 2003, just short of its sixty-fifth anniversary, the Diocese of Gallup released six names of priests credibly alleged to have sexually abused minors within its boundaries. Two years later, Bishop Donald Pelotte—the first Native American Catholic bishop in the United States—issued a public apology for the past behavior of priests in his diocese and acknowledged the need for a “search and rescue mission” to find victims, especially within Native communities. In 2013, facing the cost of mounting claims from survivors of clergy sexual abuse, the Diocese of Gallup filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

Today, in a tally of names reported by the diocese, cross-checked against those reported by Bishop Accountability, the number of Catholic leaders publicly accused of sexual abuse in the Diocese of Gallup stands at thirty-seven. Thirty-two of these men were priests, three were religious brothers, and the remaining two were a lay teacher and a former seminarian. In addition, thirteen more priests who lived in the diocese have faced sexual abuse accusations elsewhere.

These numbers are dire: The historical rate (per capita) of alleged sexual predators in the Diocese of Gallup is several times higher than the Archdiocese of Boston and the Diocese of Pittsburgh, both of which have received attention as hotbeds of Catholic abuse in the United States. The statistics are typical, though, of Catholic dioceses that reach across Indian Country. The U.S. dioceses that do have rates comparable to Gallup—including in Alaska, Montana, and South Dakota—are dioceses that contain and oversee the Catholic spiritual care of colonized peoples. From this we must conclude: Catholic sex abuse is both its own crisis and part of a legacy of sexual and gender-based violence faced by colonized people in the U.S. Southwest and across North America.

***

Today, conversations about clerical sex abuse typically feature questions about whether and how Catholic theology, doctrine, and institutional structures produced abusive actors and abusive acts—in other words, about whether and how this problem is a plainly Catholic one. Stories from Gallup and places like it don’t make these questions irrelevant, but they do require us to follow up with questions about how Catholicism produced an uneven geographic distribution of this problem and the pattern by which clerical abuse happened with special frequency to Latino and especially Native children. Why did Catholic religious leaders disproportionately abuse these populations? How do we talk about sex abuse as something that happened amid Catholic attempts at spiritual care and as colonial and racial violence?

2020 map showing the boundaries of the Diocese of Gallup

In the Diocese of Gallup, one cause of abuse was priests who spent careers moving: into its jurisdiction from other places in the United States, and from point to point through parishes and mission churches in its territory. The forces that moved these priests were Catholic ones. “Good” and “bad” priests alike were drawn to Gallup by the concern—articulated by Cardinal Pacelli during his fly-over, and later by the bishop he installed—that the Native and Latino inhabitants of the U.S. Southwest required greater spiritual care. This went hand-in-hand with the Catholic idea that men ordained to the priesthood, whether they had records of bad behavior or not, had the exclusive ability, and responsibility, to provide lay people with care necessary for their salvation, especially through administering the sacraments. The twentieth-century clerical exercise of cura animarum, or “care of souls,” drew priests along trajectories from east to west, from urban to rural, and into the Diocese of Gallup.

If care for souls who required it (or who were imagined to require it) pulled priests toward Gallup, a second force was also pushing the troubled among them—away from old haunts often located in the East, and into routes that set them on course for the Southwest. This second force came from a theology of scandal. First elaborated by Thomas Aquinas, later included in the Catholic catechism, and named as a reason for relocating priests guilty of “solicitation” of laity in Vatican-issued (but never promulgated) instructions in 1922 and 1962, scandal set the bodies of these priests into motion.

According to scandal theology, a priest’s bad acts become more sinful—additionally sinful—if faithful Catholics learn about them. In such cases, the bad acts of one man might double as “stumbling blocks” or sin-causing obstacles to proper faith for an entire community. After a priest raped a child, a well-timed relocation to a distant place could avoid scandal, and avoiding scandal could save souls.

Together these forces, the pull toward cura animarum and the push of scandal, produced a Catholic variation on a colonial theme. Gallup and places like it historically have been marked and marred by white transit. Rendered peripheral to the United States, places where colonized people continue to live become fields for resource extraction and waste disposal, sites for man camps and other assemblies of temporary labor, and simply vacant space that white bodies pass over or through. Communities there suffer the effects. Of the men accused of abuse in the Diocese of Gallup, more than three-quarters had Anglo surnames, and more than half were diocesan priests (rather than members of orders like the Franciscans or Jesuits). While it is hard to tell how many came to Gallup from elsewhere, the diocese had between six and nine of its own priests during its first year, and transit clearly built its roster of men during the middle of the century. The stories of two priests who landed in Gallup during these years, Clement Hageman and John Sullivan, demonstrate the Catholic push and pull that propelled such men into and through these places.

***

In 1940, Father Clement Hageman arrived at the Smith Lake Indian Mission on the checkerboard of tribal and allotted lands that make up the eastern edge of the Navajo reservation. Expelled from his home diocese of Corpus Christi for abusing boys, Hageman first drifted to Connecticut. Maybe he committed abuse there too; a local pastor soon wrote to Corpus Christi Bishop Emmanuel Ledvina to inform him “it gives serious scandal to many to have [Hageman] living as he is.” He urged Ledvina to (again) relocate his wayward cleric away from Connecticut and to find him “some place of refuge.”

Three months later, Hageman landed in Smith Lake, prompting the Bishop of Gallup, Bishop Espelage, to contact Ledvina. Espelage had heard that Hageman was “guilty of playing with boys,” but he desperately needed priests to work in his diocese. Should he allow Hageman to stay? The Texas bishop replied by telegram:

BELIEVE MAN MIGHT BE GIVEN A CHANCE WOULD BE IMPOSSIBLE AROUND HERE CASE TOO WELL KNOWN AROUND HERE TRY HIM OUT MAYBE MIGHT PROVE TRUSTWORTHY AT LAST.

Thus began Hageman’s career in the Southwest that spanned four decades, during which he allegedly abused dozens of minors. He became known as “the Route 66 priest” for his travel along that east-west thoroughfare. Within the Diocese of Gallup, Hageman continued to move by the same force that had pushed him out of Corpus Christi, and again Connecticut: the Catholic aversion to scandal. In 1952, Bishop Espelage relocated Hageman from Holbrook, Arizona, following reports of sexual abuse. “It is not you who is to be considered,” the bishop told the priest, “but all the Church as a whole. We cannot afford to have any kind of scandal whatever take place.” A decade later, Espelage moved Hageman again, to “prevent any further scandal.” Hageman went briefly to Utah, but soon returned to the diocese and remained there until his death in 1975. Hageman’s movements are recorded in his personnel file.

***

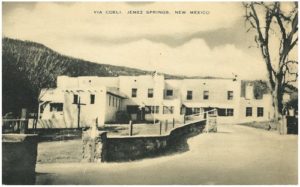

Father John Sullivan arrived in Gallup twenty years after Hageman. Sullivan was ordained in the Diocese of Manchester, New Hampshire, where his behavior with young people caused a scandal. The bishop of Manchester, Matthew Frances Brady, suspended Sullivan from ministry in 1956. One year later, Brady wrote to the Servants of the Paraclete, a Catholic order dedicated in ministry to troubled priests. The bishop asked its founder, Father Gerald Fitzgerald, if he would accept Sullivan at the Via Coeli monastery and “renewal center” in the Jemez Mountains east of Gallup. “His problem is not drink, but a series of scandal-causing escapades with young girls,” Brady explained.

Fitzgerald refused to receive Sullivan at Via Coeli unless the priest promised to remain in its confines for life. “A new diocese means only green pastures,” Fitzgerald cautioned. “I do not dare recommend such men for the cura animarum.” For five years, Sullivan refused Fitzgerald’s precondition. During that time he tried, without success, to find his own greener pastures: seventeen dioceses would deny Sullivan’s request for reassignment. He also continued to abuse minors.

In 1961, Sullivan relented and agreed to go to New Mexico, and by the time he relocated, something at Via Coeli had changed. Within months Sullivan was permitted to move from the facility into Gallup to substitute for a sick pastor on an “emergency” basis. Bishop Espelage “hoped to keep [Sullivan],” Fitzgerald soon reported, “as he was [..] very much liked by the poor Mexican people among who he was working.” Sullivan remained in Arizona until the early 1980s and allegedly abused multiple victims there. A portion of Sullivan’s personnel file is available here.

***

Via Coeli

Via Coeli was a site where scandalous priests gathered and relocated through the Southwest. At least a half dozen priests (and likely more) later accused of abuse in Gallup made their way into its churches and missions via the monastery. Within the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, which encompassed the Jemez region and Via Coeli, that number is higher. Whether priests passed through Via Coeli as Sullivan did, or whether they traveled directly to ministry in Gallup as Hageman did, the dislocation caused by the threat of scandal, coupled with the pull created by the Church’s determination that rural Native and Latino communities needed greater spiritual care, brought predators to the Southwest. This push-and-pull is clear in John Sullivan’s own search for new work during the 1950s. “I know [..] that there are not too many Bishops who desire saddling their dioceses with problems such as my many weaknesses unfortunately tend to present,” he wrote to Bishop Brady. But some dioceses badly required help, and so Sullivan saw his chance to return to cura animarum. “It appears to me that there are some Western Dioceses that are in need of priests,” he assured his superior. “This decision [..] will first of all please God, and at the same time enable me to piece together my broken priesthood.”

To talk about priests moving across a U.S. “Indian diocese” as a way of explaining Catholic sex abuse in colonial geographies is to identify one theme in a complex historical problem. Diocesan priests were not the only men who abused; in other places with Indian missions, members of religious orders comprise most of the accused. Even in the Diocese of Gallup, more than a dozen of those accused of sexual abuse were Franciscan priests or brothers.

Nor is abuse in these places solely the result of priests moving from far away. There is a second explanation, for example, embedded in the way of life dictated by Catholic Indian missions. Although in Gallup the men accused of abuse usually (though not always) staffed churches, elsewhere across Indian Country abuse claims cluster around schools, and boarding schools especially. Inside such institutions, the regimen Catholic adults imposed on Native students—routines that enforced intimacy of sleeping and bathing, and claustrophobic relationships between teachers and pupils—became a cause for abuse by priests (and in significant numbers, also Catholic sisters) who arrived to work in missions with no prior evidence of bad behavior. Like the Catholic forces that moved men, these Catholic regimens were one cause of abuse that also replicated colonial and racial patterns of violence.

***

My purpose here has not been to prove that Catholic leaders moved predator priests to places like Gallup, with large Native and Latino populations, because they believed young people in such places were less harmed by sexual violence, or because their parents would be less likely to successfully protest to religious or secular authorities—though to be clear, beliefs like these were shared among, and informed decisions of, the midcentury Church hierarchy and priests themselves. My concern is instead with how Catholic theology, doctrine, and institutional structures—working in tandem with these racially structured assumptions—aggravated the problem of sex abuse in colonized places. The restless drift of priests, amid the push and pull of Catholic sensibilities about sin, on one hand, and spiritual care, on the other, exposes interlocking systems of religion, race, and colonialism that produced Catholic abuse in places where it was the worst. As a site made by this motion, the Diocese of Gallup is at the crux of the problem of religion and sex abuse in the United States.

Kathleen Holscher is associate professor of religious studies and American studies, and holds the endowed chair in Roman Catholic studies, at the University of New Mexico.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.