Dying to Be Normal: Gay Martyrs and the Transformation of American Sexual Politics

Revealer Editor, Kali Handelman, interviews Brett Krutzsch about his new book Dying to Be Normal: Gay Martyrs and the Transformation of American Sexual Politics

Brett Krutzsch’s book, Dying to Be Normal: Gay Martyrs and the Transformation of American Sexual Politics, is a model study — clear, nuanced, and unnervingly prescient — of the complicated relationship between religion and media and how they shape our political present. His synthetic and intersectional approach to Christianity, memory, sexuality, gender, race, and politics should have a place on just about anyone’s reading list or syllabus. I was thrilled to have a chance to speak with Krutzsch about his work earlier this summer.

***

Kali Handelman: I want to start by asking you about your research, and about themes and terms that you use in your incredibly rich and far-reaching analysis. Can you tell me a bit about how you came to this topic and your perspective on it? Were you surprised by where your research led you?

Brett Krutzsch: I came to the topic because I was troubled by the popularity of the It Gets Better campaign as a response to LGBT teen suicides. I found it strange that so many Americans supported the idea that life improves for LGBT people simply because they get older. And yet, people I respect made their own It Gets Better videos, as did numerous heterosexual politicians and celebrities. I wanted to think through the messages the campaign promoted that allowed it to resonate so broadly in the culture. Part of the answer for its widespread approval, I believe, has to do with how It Gets Better promotes secular Christian messages that many Americans accept as commonsense ideas rather than as specifically Christian ones. One example from It Gets Better is the idea of redemptive suffering, the Christian idea that suffering and death can have a purpose, and that, like Christ’s suffering on the cross or Christian martyrs in the Coliseum, one’s trials today can lead to a better tomorrow. But there is no guarantee that traumas lead to anything better, individually or collectively. And yet, many people, including LGBT activists and scholars, promote such ideas even though they likely do not see themselves as reinforcing veiled Christian dominance, which, for me, underscores how insidiously certain aspects of Christianity have shaped our culture and political possibilities.

After I wrote an essay about the religious and racial messages that supported the It Gets Better campaign, I started to think about other times in American history when religion, death, and LGBT politics came together. That line of questioning took me to Matthew Shepard’s murder in 1998. His memorialization and “martyrdom” are saturated with religion—far more explicitly than in the It Gets Better campaign—so I wanted the book to consider this interplay of religion, death, and LGBT politics, what it means to make people into martyrs, and how that process has shaped the parameters of LGBT inclusion in the United States.

KH: You do a really outstanding job of analyzing media — news, film, television, theater — in your book. Were you drawn to this subject by that media, or were you drawn to the media by your subject?

BK: Thank you. To understand the cultural effects of various LGBT “martyrs,” I wanted to examine how they were memorialized, reported on, venerated, and condemned. That inquiry took me to diverse forms of media, often with recurring themes across journalism, film, and theater. I was also interested in analyzing media because many LGBT activists have used media to bring attention to their political issues. With this, the book especially focuses on how queer people of color and transgender activists have used film to try to get the country to care about the ongoing violence done to their communities. Beyond that, I wanted to demonstrate the importance of looking for religion in places far removed from temples and churches. Protestant Christianity’s power, I hope the book shows, spreads beyond the spheres of church and home and is all the more powerful because most people are not taking note of it.

BK: Thank you. To understand the cultural effects of various LGBT “martyrs,” I wanted to examine how they were memorialized, reported on, venerated, and condemned. That inquiry took me to diverse forms of media, often with recurring themes across journalism, film, and theater. I was also interested in analyzing media because many LGBT activists have used media to bring attention to their political issues. With this, the book especially focuses on how queer people of color and transgender activists have used film to try to get the country to care about the ongoing violence done to their communities. Beyond that, I wanted to demonstrate the importance of looking for religion in places far removed from temples and churches. Protestant Christianity’s power, I hope the book shows, spreads beyond the spheres of church and home and is all the more powerful because most people are not taking note of it.

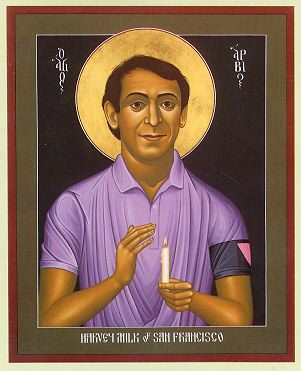

KH: I want to ask you a few questions about some of the concepts and terms you use to make your arguments. The first concept I was hoping to hear more about is “the cultural currency of Christianity” which you use to describe what shaped the way American gay rights activists memorialized Harvey Milk, making him (a Jew) into a “ Christianized martyr for the national gay rights movement.” Can you tell me more about what you mean by “cultural currency”? It seems like a really useful way of talking about the power of religion that isn’t narrowly theological or deterministic.

BK: Exactly. By “the cultural currency of Christianity” I mean that some Christian images, ideas, and rhetoric are so well known in the United States that Americans, including non-Christians and LGBT activists, can use them and find that their target audiences have an immediate reference point that establishes possibilities for recognition and, if desired, political alliance. Put another way, Christianity as “cultural currency” can render people, and activist movements, relatable to the “general” American public. Jewish and Muslim traditions do not have the same level of cultural currency. Harvey Milk was a secular Jewish, Yiddish-speaking, anti-monogamist. To make him appeal to the predominantly Christian country, to both straights and gays, activists tapped into the cultural currency of Christianity. That does not mean they turned him into someone who believed Jesus was God. But it does mean that many downplayed his Jewishness, depicted him as committed to coupled fidelity, and presented him as someone whose death, like Christ’s crucifixion, transformed the world. Multiple activists, playwrights, and museum curators memorialized Milk as both crucified and resurrected. By thinking about the cultural currency of Christianity and how it gets deployed in secular spaces, we can begin to see the narrowness of political projects where people are seen as more valuable if they reflect, or can be made to reflect, recognizable Christian images and ideas.

KH: Your book read, in many ways, as a critique of assimilationist political activism. In your conclusion, you describe how the group Gays Against Guns (GAG), formed in the wake of the Pulse Nightclub shooting, “represented a move away from assimilationist tactics and a turn toward a queer ethic of dismantling society’s norms.” Are you, in a sense, offering a queer ethic(s?) as an alternative kind of politics? Rather than assimilation, a queer ethics of anger, frivolity, disruption, and provocation? Does that sound right? Can you tell me more about what this queer ethic would look like? And how might religion fit in? Are there other examples you’d like to share?

BK: Yes, that sounds right. While I’m not an ethicist, the history of LGBT politics does not seem to suggest that assimilation creates vastly greater sexual or gender freedoms beyond the “freedom to marry.” Certainly, assimilation has benefited some, especially white cisgender gays who are interested in monogamous matrimony and serving in the military. But assimilationist political activism tacitly, and often unwittingly, reinforces the white, Christian, gender-conforming nuclear family as the cultural ideal. A queer political ethic would make visible how the nuclear family is one of the most common sites of violence and trauma in this country. From childhood sexual abuse to domestic violence, as well as cultural pressures to love one’s family no matter how damaging and abusive they become, the family is a fraught and, for many, dangerous institution. But that critique gets overlooked through assimilationist politics, which, I should add, feminist scholars have been saying for decades. That is why I write in the book’s Epilogue that if you want to venerate Harvey Milk, make visible that he was a Jew who rejected the Protestant sexual standard of coupled monogamy. He developed his own sexual ethic that emphasized how communities could become stronger if people felt free to love more than one person at the same time, and where people believed they could be honest with everyone about their concurrent romantic and sexual relationships.

BK: Yes, that sounds right. While I’m not an ethicist, the history of LGBT politics does not seem to suggest that assimilation creates vastly greater sexual or gender freedoms beyond the “freedom to marry.” Certainly, assimilation has benefited some, especially white cisgender gays who are interested in monogamous matrimony and serving in the military. But assimilationist political activism tacitly, and often unwittingly, reinforces the white, Christian, gender-conforming nuclear family as the cultural ideal. A queer political ethic would make visible how the nuclear family is one of the most common sites of violence and trauma in this country. From childhood sexual abuse to domestic violence, as well as cultural pressures to love one’s family no matter how damaging and abusive they become, the family is a fraught and, for many, dangerous institution. But that critique gets overlooked through assimilationist politics, which, I should add, feminist scholars have been saying for decades. That is why I write in the book’s Epilogue that if you want to venerate Harvey Milk, make visible that he was a Jew who rejected the Protestant sexual standard of coupled monogamy. He developed his own sexual ethic that emphasized how communities could become stronger if people felt free to love more than one person at the same time, and where people believed they could be honest with everyone about their concurrent romantic and sexual relationships.

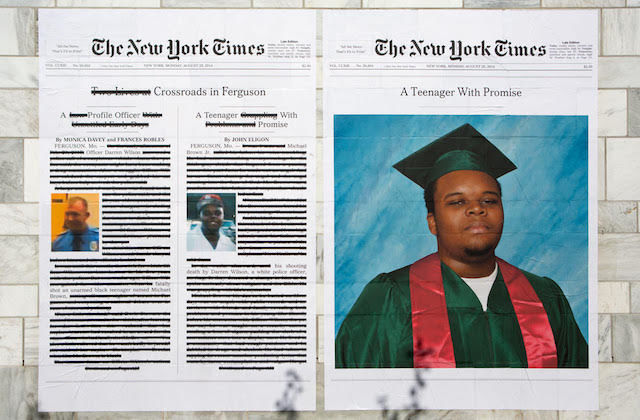

KH: On a related note, your book also read to me as a push toward an intersectional critique of respectability politics. This seemed clearest in your chapter on Matthew Shepard, about whom you say:

In effect, references to [Matthew] Shepard as an “all-American,” “kid next door,” and “anyone’s son,” functioned as coded rhetoric for white, middle class, Christian youth, which served to highlight that had Shepard not been gay he would have been part of—indeed, at the top of—the American social hierarchy.

Which made me think immediately of how black boys and men who have been killed by the police are described so differently, if still religiously. For instance, how the police officer who killed Michael Brown said he looked like “a demon” and The New York Times described him as “no angel” (a line we can add to the list of jaw-dropping headlines and phrases you cite from the paper of record). Can the questions you ask in your book help us think about how to move away from respectability and assimilation and toward (a queer ethic of?) fully valuing lives that aren’t white, middle class, Christian, and monogamous?

BK: I really hope so. We cannot think of this country’s race problem as separate from LGBT politics. It is not a coincidence that the vast majority of murdered transgender women—year after year—are people of color. While writing the book, I wanted people to see how “mainstream” institutions like the New York Times can venerate Matthew Shepard, a white gay college student who was violently assaulted, as nearly perfect and then describe black lesbians who were attacked in a homophobic assault as a violent “gang.” I never needed to turn to places like Fox News to make visible how narrow the parameters of LGBT acceptance have been within “mainstream” America and how those parameters have had much to do with race and, importantly, religion. Feminist, Queer, and Religious Studies scholars have not paid nearly enough attention to the role of religion in shaping cultural ideas about which lives and deaths matter. Race is certainly and inarguably a prominent factor. But so is religion. It is also not a coincidence that Matthew Shepard, the first LGBT American whose death mattered instantly to this country, was a practicing Protestant.

“A Teenager with Promise” by Alexandra Bell at Bennington College, provided on December 8, 2017. Photo: Keegan Ead/Usdan Gallery at Bennington College

KH: Throughout the book, I saw you pulling on a discursive thread that uses the language of “epidemics” to describe both the medical/political stories of HIV and AIDS and the social/political phenomena of bullying, violence against transgender people, and guns. Why do you think we reach for this biological language to describe these problems and in what ways is it harmful or helpful?

BK: Biological language has an appearance of factuality that many people take seriously. HIV/AIDS was certainly a medical epidemic. Ironically, as Anthony Petro has demonstrated, throughout the early years of the AIDS epidemic, various people involved in politics referred to AIDS with religious language and described it as a symptom of God’s displeasure with homosexuality. Rhetorically, activists have garnered attention for bullying, gun violence, and, to a lesser degree, murderous violence against transgender women by describing them as “epidemics.” I am less convinced that such rhetoric and recourse to biological language has produced much cultural change. Gun violence remains a nightmare. For that matter, so does violence against transgender women of color. And, as I explore in the book’s third chapter, I am concerned by how the widespread focus on “bullying” as an “epidemic” disproportionately projects anti-LGBT attitudes onto adolescent “bullies” while concurrently allowing average heterosexual adults to avoid taking responsibility for how they uphold values and institutions that reinforce oppressive sexual and gender hierarchies.

KH: I also wondered how you decided on the terminology of “emblems” and “emblemization.” The concept of emblems seems, to me, to activate thinking about civil religion and who/what can be symbolically sacred, but I wonder where you were drawing it from and how you might want to encourage us to think about other emblems?

BK: My thinking on emblems drew from a rich body of scholarship on martyrdom by people like Elizabeth Castelli and Candida Moss. They make the point that martyrs-as-emblems almost always better reflect the people who do the emblemizing than they do the people who have been emblemized. In other words, martyrs-as-emblems can be changed into more widely respectable figures than they were during their lifetimes. They can also be used to advance political positions that they did not address when they lived. This certainly happened with Harvey Milk, but also with other well-known martyr-emblems like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I was also informed by Jewish Studies scholars like Jodi Eichler-Levine and Liora Gubkin who have written on why Anne Frank became the emblematic Jew who American Christians posthumously cared about following the Nazi genocide of six million Jews. Their insights shaped some of my thinking about Tyler Clementi and Matthew Shepard. Emblems are tricky, especially when the goal is to appeal to the country’s dominant class of white, straight Christians. On the one hand, someone like Matthew Shepard seems relatable to white Christians. But how much social change can really take place when the major emblems of the LGBT movement, the “symbolically sacred” as you incisively note, have appeared so similar to America’s white, Christian, gender-normative dominant class?

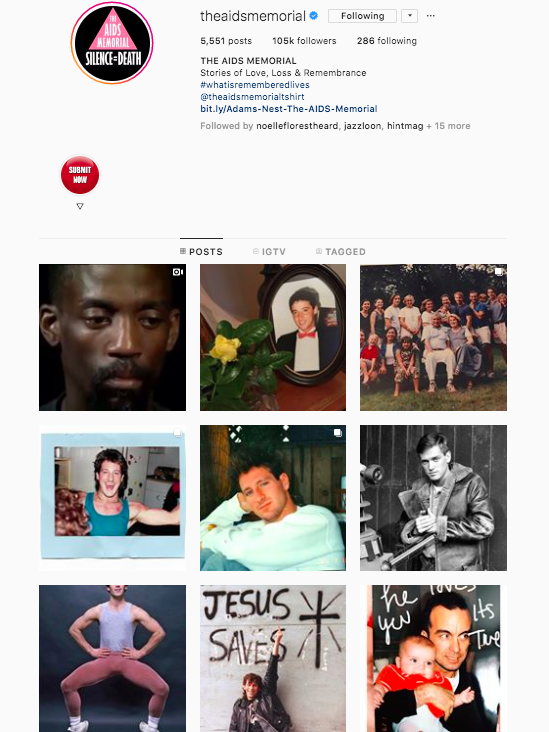

KH: I wonder if you’re familiar with the Instagram account, The AIDS Memorial, in which people share “Stories of Love, Loss & Remembrance” about loved ones who have died of complications due to AIDS. Do you see this as another facet of the story you’re telling, and/or is this an example of ways that commemoration practices can change as media and culture change?

KH: I wonder if you’re familiar with the Instagram account, The AIDS Memorial, in which people share “Stories of Love, Loss & Remembrance” about loved ones who have died of complications due to AIDS. Do you see this as another facet of the story you’re telling, and/or is this an example of ways that commemoration practices can change as media and culture change?

BK: Yes, and I find that Instagram account quite moving. AIDS history is incredibly important and not discussed or taught nearly enough. The AIDS Memorial Instagram page uses social media to add to our collective archive about a profoundly dark period in this country’s recent past. In many cases, people with AIDS in the 1980s and early 1990s were despised and, in many other instances, flagrantly ignored. Countless people with AIDS were abandoned by their families, ignored by hospital employees who refused to touch them, and turned away from funeral homes that did not want a reputation for conducting AIDS funerals. There are also remarkable stories of activism that the AIDS epidemic ignited, and countless tales of lesbians who volunteered to care for dying gay and bisexual men who had no remaining loved ones to look after them. But I do not want to suggest, nor would I support any memorial that suggests, a redemptive reading of America’s AIDS history. The history of AIDS in the United States is a story of vitriolic homophobia, pervasive racism, government negligence, and an overwhelming lack of concern about a horrifying epidemic that devastated the LGBT community.

KH: I also have to ask about Pete Buttigieg. You mention at one point that Matthew Shepard’s mother “insisted that no one would choose to be gay because of the prevalence of anti-gay violence. However, critics of the “born gay” perspective warned that it tacitly implied all other [non-heterosexual] sexualities were an aberration.” Which reminded me of a recent piece by Masha Gessen in The New Yorker in which she responds to how Buttigieg has spoken about his sexuality:

The argument on behalf of gay rights that gay people have no choice but to be gay is humiliating because it assumes that one kind of sexuality is desirable and that any deviation is, at best, acceptable. If it were a choice, the argument implies, only one choice would be valid. This is a basic argument for the right of queer people to exist: because they can’t help it. By giving it a religious framing, Buttigieg presented the humiliation inherent in the argument as something else—humility. Given that the argument is the premise of the political gay-rights movement, it is inevitable that the first openly gay Presidential candidate would speak of his sexuality in these terms. It is also chilling that, at a moment when it seems conceivable, at least for a minute, that a gay man could mount a successful bid for the Presidency, he also has to advance an argument for his right to be.

I wonder how you’ve been thinking about his candidacy and what it says about the discourse and history you outline so clearly in your book?

BK: Pete Buttigieg’s success supports many of my book’s main arguments. Pete Buttigieg is basically Matthew Shepard grown up and living a political life. Like Shepard, Buttigieg is white, gender-conforming, and importantly, a practicing Protestant member of the Episcopal Church. He is a safe, “normal” gay, made more palatable to the heterosexual public through his mainline Protestantism. On the national stage, the relatable gay American, it certainly seems, needs to appear religious in ways that align with the ideals of white, mainline Protestant Christianity, which, again, underscores the cultural currency of Christianity. Buttigieg would not have been as successful as the first openly gay presidential candidate if he were a Reform Jew. He frequently talks about his Christianity in ways that resonate broadly. Effectively, the committed gay Christian comforts those who worry about gays and their sexual morality. And therein lies one more significant hurdle for mainstream LGBT acceptance, especially for gay men, and that is the issue of sex. Sure, Donald Trump can have extramarital sex with porn stars, but that would not fly for Buttigieg since many straight Americans, even so-called “accepting” ones, are uncomfortable with queers who flaunt the Protestant sexual standard of coupled monogamy. With Matthew Shepard, LGBT activists dealt with this concern by turning the 21-year-old Shepard into a nonsexual adolescent, frequently calling him a “kid” and “anyone’s son.” Buttigieg avoids prolonged fixations on his sexual habits by saying his marriage to his husband brought him closer to God. Fear not skittish straights, this success story suggests, for Buttigieg is a gay American who will keep his sexuality contained to his monogamous marital bed and obey the vows he made in front of God in his Midwestern Protestant church.

BK: Pete Buttigieg’s success supports many of my book’s main arguments. Pete Buttigieg is basically Matthew Shepard grown up and living a political life. Like Shepard, Buttigieg is white, gender-conforming, and importantly, a practicing Protestant member of the Episcopal Church. He is a safe, “normal” gay, made more palatable to the heterosexual public through his mainline Protestantism. On the national stage, the relatable gay American, it certainly seems, needs to appear religious in ways that align with the ideals of white, mainline Protestant Christianity, which, again, underscores the cultural currency of Christianity. Buttigieg would not have been as successful as the first openly gay presidential candidate if he were a Reform Jew. He frequently talks about his Christianity in ways that resonate broadly. Effectively, the committed gay Christian comforts those who worry about gays and their sexual morality. And therein lies one more significant hurdle for mainstream LGBT acceptance, especially for gay men, and that is the issue of sex. Sure, Donald Trump can have extramarital sex with porn stars, but that would not fly for Buttigieg since many straight Americans, even so-called “accepting” ones, are uncomfortable with queers who flaunt the Protestant sexual standard of coupled monogamy. With Matthew Shepard, LGBT activists dealt with this concern by turning the 21-year-old Shepard into a nonsexual adolescent, frequently calling him a “kid” and “anyone’s son.” Buttigieg avoids prolonged fixations on his sexual habits by saying his marriage to his husband brought him closer to God. Fear not skittish straights, this success story suggests, for Buttigieg is a gay American who will keep his sexuality contained to his monogamous marital bed and obey the vows he made in front of God in his Midwestern Protestant church.

KH: I’d love to hear about what you’re working on next! Do you have something in the works

BK: Yes, I am currently co-editing a book with Nora Rubel that explores the television show Transparent and what that show reveals about transgender representation, queer politics, Jews in America, and religion in the second decade of the 21st century. It takes my interest in media, religion, and queer politics in an exciting and rich direction. I am also co-writing a chapter for an edited volume with Samira Mehta where we are comparing the history of Jewish institutional responses to interfaith marriage with Jewish institutional responses to same-sex marriage. And, I am working on an essay that explores the religious and queer encounters of Dr. Joycelyn Elders, the first black woman to serve as Surgeon General of the United States who President Clinton forced to resign in 1994 when she said children should be taught about masturbation.

KH: Because you are clearly so interested in popular culture and media, I wonder if you could tell us what you have read, watched, or listened to recently that you would recommend readers pick up (once they’ve finished your book, obviously)?

BK: Yes, first, and this is not only because of my current writing projects, but I think everyone should watch both Transparent and Pose. They deal with transgender representation and queer politics rather differently. Neither is perfect, but I recommend both. Transparent’s portrayal of Jewishness—as a religion, as an ethnicity, as an identity rooted in historical trauma—is layered and compelling. Pose does not address religion as much, although religion appears in the series, but it does a fine job of illustrating some queer history from the AIDS epidemic—especially that of black drag, trans, and gay people in the New York City ball scene. For analysis of present-day politics involving gender, sexuality, and religion, check out Jay Michaelson’s writing in the Daily Beast. And, for current takes on contemporary queer life, I recommend following Slate’s “Outward” articles and podcast, and Andrea Long Chu (@theorygurl) on Twitter.

***

Brett Krutzsch is Visiting Assistant Professor of Religion at Haverford College. His scholarship explores religion, sexuality, queer history, and U.S. politics. He is the author of Dying to Be Normal: Gay Martyrs and the Transformation of American Sexual Politics (Oxford University Press, 2019).