Religious Freedom, Weapon of Choice

Rethinking American assumptions about liberty and history.

A detail from the base of a statue of Thomas Jefferson on the campus of UVA.

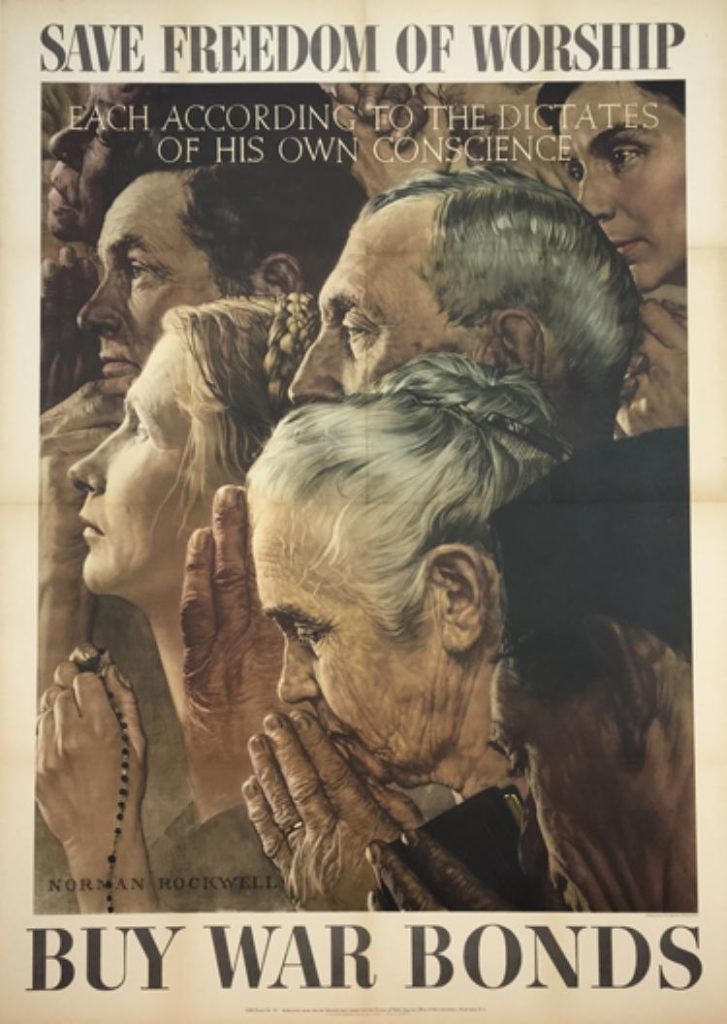

On April 29th, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom will hold an event rolling out its annual report on the state of religious freedom in the world. Mandated by the 1998 International Religious Freedom Act, the annual report documents global infringements on religious liberty and designates “Countries of Particular Concern” that allegedly violate religious freedom. The message at these rollout events is simple: The United States has religious freedom. Other countries do not. America is uniquely positioned to give religious freedom to the world.

Similarly triumphalist accounts characterize “Religious Freedom Day,” the January 16th anniversary of the 1786 Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom. Since 1993, presidents of both parties have used this anniversary to reiterate the founding myth of America as a land of religious freedom. In his 2019 statement, for example, President Trump recalled the heroic travels of religious minorities who crossed the Atlantic to escape religious persecution.

This transatlantic story of religious freedom makes America a star in the global drama of religious freedom. It suggests reassuring progress from Anglican religious oppression to American religious freedom. It also implicitly privileges whiteness. Recapitulating this story year after year places the origins of the United States in Europe rather than in the vast and diverse civilizations that predated Europeans’ arrival on the American continent. It also erases the abhorrent transoceanic passage of enslaved human beings like my African ancestors, who crossed the Atlantic as cargo in the holds of ships rather than as pilgrims in pursuit of freedom.

If we are going to reflect on religious freedom year after year, then there is a different transoceanic story that we can and should tell. This alternate story is no less patriotic. But rather than looking east across the Atlantic to the oppression “we” left behind, this story looks instead at what settlers did with the concept of religious freedom once they arrived and moved west.

When we shift attention away from the Atlantic and consider the Pacific, as scholars such as Tisa Wenger and Anna Su have done, we see that religious freedom has a long, sordid history as a tool of American empire. Simply put, settlers who called themselves “white” weaponized religious freedom. On the American continent, they used religious freedom as a legal tool to dispossess Natives of land. Moving west across the Pacific, they used religious freedom to snap up lucrative real estate in the sovereign Kingdom of Hawai`i, to establish unequal treaties with the sovereign state of Japan, and to establish discriminatory practices in the colonial Philippines.

As I show in my new book, Faking Liberties: Religious Freedom in American-Occupied Japan, this imperial project continued well into the middle of the twentieth century. Americans stationed in Japan at the close of World War II claimed to bring religious freedom to the occupied nation. In their account, they came to emancipate Japanese people from a theocratic state that confused religion (Shintō) with politics. But some Americans at the time, including Supreme Commander Douglas MacArthur, made the Occupation into a theocratic project of their own by suggesting that Japan’s democratization required the Christianization of the entire population.

The situation was rife with irony. Officials in charge of promoting religious freedom decried Japan’s politicized shrine rituals as inimical to religious freedom. In the same breath, they touted “the guiding tenets of our Christian faith” as the basis for Occupation political reforms. These Americans were either unable to see how they engaged in the very sort of sanctified politics that they accused the Japanese of, or they saw the similarities but did not care. As former occupier William P. Woodard later drily noted in his 1972 memoir, “the Japanese extremists did not have any monopoly when it came to using religion, including Christianity, for the achievement of political ends.”

The occupiers’ triumphalist narrative also overlooked a simple historical fact. They claimed to be bringing religious freedom to Japan, but Japanese people had been vigorously debating the meaning and scope of their own constitutional religious freedom guarantee for decades before the occupiers even arrived. Japanese citizens used their constitutionally guaranteed freedom of expression to deliver speeches, write impassioned op-eds, lobby elected representatives, and protest legislation they found unfair. When the situation demanded it, Japanese lawyers and diplomats proudly defended Japanese religious freedom policy on the world stage. Japanese expatriates called the United States to account when they suffered religious discrimination on American shores. And until war broke out between the two countries in December 1941, periodic reports from American foreign service officers stationed in Japan explicitly stated that Japanese practices of religious freedom were hardly different from those in the United States.

The occupiers’ triumphalist narrative also overlooked a simple historical fact. They claimed to be bringing religious freedom to Japan, but Japanese people had been vigorously debating the meaning and scope of their own constitutional religious freedom guarantee for decades before the occupiers even arrived. Japanese citizens used their constitutionally guaranteed freedom of expression to deliver speeches, write impassioned op-eds, lobby elected representatives, and protest legislation they found unfair. When the situation demanded it, Japanese lawyers and diplomats proudly defended Japanese religious freedom policy on the world stage. Japanese expatriates called the United States to account when they suffered religious discrimination on American shores. And until war broke out between the two countries in December 1941, periodic reports from American foreign service officers stationed in Japan explicitly stated that Japanese practices of religious freedom were hardly different from those in the United States.

To be very clear, this is not to say that things were fair for all. In both countries, minority religious groups were surveilled. In both countries, policy makers and police justified suppression by designating minority groups as not really religious and therefore undeserving of freedom. Examples include the incarceration of Japanese American Buddhists in the United States and the violent attacks on groups like Ōmotokyō and Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai in Japan. But the occupiers’ narrative only accounted for the Japanese side of the story. America had religious freedom, Japan did not.

Despite their confident assertions about how they were bringing “real” religious freedom to Japan, the occupiers vehemently disagreed with one another about what religious freedom was. The bravado in the occupiers’ rhetoric masked their anxieties about how to properly draw the line between religion and politics. For example, the occupiers were internally divided over whether postwar democratization necessitated stripping religion from public education altogether, or whether preparing Japanese citizens for democratic life required formal religious training in public schools. These anxieties matched debates then raging in the United States regarding the constitutionality of the flag salute, confessional education programs, public tax expenditures on parochial schools, and school prayer.

Another irony concerns who actually constructed the concepts that undergirded Occupation religious freedom policy. In the rare moments when the occupiers did speak in a unified voice about protecting religious freedom, they did so with the help of terms provided to them by Japanese experts who served as their local advisors. For example, scholar of religion Kishimoto Hideo and legal scholar Minobe Tatsukichi helped the occupiers position “State Shintō” as a foil for “real religious freedom” by writing op-eds and accessible pamphlets describing the postwar legal regime. Illustrated Japanese-language primers on Japan’s new constitution depicted “real religious freedom” by showing three members of a family practicing three different religions.

In this sense, the Americans did not bequeath religious freedom to the Japanese people. Rather, Japanese elites helped the Americans reinvent religious freedom as a timeless, innate, universal human right. By collaborating with the occupiers, local elites aligned themselves with political authority and positioned their ideas as essential to social progress. By borrowing language provided by these local experts, the occupiers were able to make religious freedom seem theologically neutral (not god-given) and culturally odorless (not exclusively American). These collaborations created the intertwined notions that all people are naturally religious from birth, that each individual must choose just one religious affiliation, that some religions are better choices than others, and that some ritual practices do not count as “religion” at all.

This coercive model of freedom, created under the circumstances of military occupation, presented a paradox. In a country where most people had previously held pluralist understandings of religious affiliation and practice, now they were not only able to choose their religions. They had to. And when they chose, the occupiers and Japanese elites told them they needed to choose well: Personal, not collective. Peaceful, not violent. Rational, not superstitious.

We therefore have to ask: Whose purposes did the triumphalist account serve? Who did it make look good, and who bad, when the occupiers and their elite Japanese informants claimed that America “had” religious freedom and Japan did not?

We are reminded of the American story of religious freedom year after year. This national narrative certainly deserves careful, ongoing attention. But perhaps a more patriotic account would be characterized by humility rather than hubris. Instead of assuming that Americans naturally know what religious freedom is, we might look at moments like the Occupation of Japan when people of other nationalities have helped us think about how everyone might be free. Instead of assuming that religious freedom made the America that we know today, we might ask how Americans have made—still make—religious freedom into a weapon of choice.

***

Jolyon Baraka Thomas is assistant professor of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author of Faking Liberties: Religious Freedom in American-Occupied Japan. His Twitter handle is @jolyonbt.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.