RIP: Public Funerary Rituals for American Celebrities in Turkey

Why are people in Turkey memorializing Aretha Franklin and Michael Jackson?

A couple of days after Aretha Franklin died last August, locals in Karaburun, a small town on the Aegean coast of Turkey, ate lokma—fried donuts dipped in sweet syrup— in her memory. While “Respect” blasted in the speakers next to a mobile donut maker, passers-by walked away with lokma in their hands and prayers for Franklin’s soul on their lips. Nobody seemed surprised by the sight, though, perhaps because the man hosting this memorial, archeologist Ahmet Uhri, a Karaburun local, had carried out the same ritual when Stephen Hawking passed away a few months earlier.

Public funerary rituals with a charity component have been organized for famous figures in different parts of Turkey for a long time now. Back in 2009, multiple death rituals were organized for Michael Jackson in Midyat —a small town in the southeast region of Turkey— attracting international attention. That June, Midyat locals joined Jackson’s fans across the globe in commemorating the King of Pop by performing a funeral service (Jackson’s body, of course, in absentia) and reciting prayers for the soul of the singer in five languages.

The commemorations in honor of Jackson were organized by Mehmet Ali Aslan, head of the Mıhellemi Association for Dialogue between Religions, Languages and Civilizations, based in Midyat. Founded in 2008, the association’s mission is revitalizing the culture, language, and “civilization” of the Mıhellemi community, which is an Assyro-Arab community of Sunni Shafi’is living in Turkey and abroad.[1] The association organizes events and oral history projects in order to promote this community’s cultural diversity within what they call “the Semitic communities” located in Turkey. When interviewed about the rituals for Jackson’s soul, Aslan explained that it made sense to carry out these rituals because Jackson was part of the extended Mıhellemiler family by marriage. The Mıhellemiler claim that Elvis Presley was from a branch of their family who migrated to Latin America and then the US. Because Michael Jackson was once married to Lisa Marie Presley, the daughter of the King of Rock n’ Roll, the King of Pop was also a part of the Mıhellemiler family.

These rituals—deeds and charity in the name of the deceased—not only continue a person’s positive impact on the community, but they also add positive points on an individual’s “deed pages.” Deed pages, as mentioned in the At-Takwir sura of the Qur’an, are the record of a person’s good and bad deeds. According to the sura, these pages will constitute the basis for God’s Judgment Day decision whether to put an individual in heaven or hell.

But why are Muslims in Turkey celebrating these — not Turkish, not Muslim, not blood-related — stars with traditional rites?

When I first read the news reports on these rituals, I was puzzled: admiration for rock royalty cannot totally explain it. For one thing, these rituals and commemorative events require money, time, and labor. Professionals may be responsible for physically preparing the lokma at a mobile donut station on a sidewalk near the house of the deceased, but the family of the deceased runs the show.

As a Sunni Muslim from Izmir (Turkey’s third largest city, located on its Western coast), I know from personal experience that distributing lokma in the name of a deceased family member is challenging. When we organized a lokma giveaway on the seventh day after my own father’s death (as the tradition suggests), I was the one who instructed the lokma makers where to park and set up shop. As they heated vegetable oil in a huge pan, and started dropping dough into the heated oil on a busy sidewalk, I strategically placed the tables at a busy corner of the street. I also put my father’s picture up by the tables, along with a small sign carrying his name and a simple request “Ruhuna Fatiha.”[2]

Where you set the lokma stand is important. It should be a busy spot so the fried lokma doesn’t get soggy waiting for too long in the syrup and because the aim is to give them to as many people as possible, including community members who didn’t know the person being celebrated. So on that seventh day after his death, we set up our lokma stand on a bustling corner where we could give as many passers-by as possible a (sweet) reason to pray for my father’s soul.

For an hour or so, passers-by got in line to take plastic bowls of four or five lokmas covered in syrup and cinnamon powder. Some came with their own big bowls in order to take enough for the whole family. Elderly neighbors with diabetes asked for less or no syrup and children came back for seconds. Everyone said the same thing to me, though: “Allah kabul etsin” (May Allah accept your deed).” As people recited El-Fatiha, I was still in disbelief, holding back my tears, thanking people for their prayers.

A year later, at another lokma stand, I learned that time does, in fact, heal pain. On the first anniversary of his death, my family hosted a second lokma stand for my father. But at the anniversary ritual, I spent most of the time smiling, remembering the good times with him, celebrating his life, and thinking about how his death, though it still hurt, was now something sweet in the passers-by’s lives.

However meaningful, the lokma ritual is costly. If we were to repeat the lokma give-away my family performed for my father we would spend 300 Turkish liras or approximately $57 US dollars. That may not sound like very much to spend to feed so many people, but the average monthly wage in Turkey is currently 1603 liras, or about $303. The high cost means that not everyone can carry out these rituals in the same way. Some people in Turkey opt for more modest ways to commemorate their loved ones, choosing instead to hand out candy or homemade desserts, which are cheaper and less complicated.

This is all to say, one would need a profound reason to perform this ritual for anyone, particularly someone who was not even a part of your family. Aretha Franklin, Michael Jackson, Stephen Hawking — they have to mean something more to people than just their status as celebrities.

***

For Ahmet Uhri, the archeologist who distributed lokma in honor of Aretha Franklin and Stephen Hawking, Franklin didn’t mean a lot when he first listened to her as a child. He first heard her voice from a record his American tenants played for him. But when, as an adult, Uhri got to know more about Aretha Franklin and her activism, he came to admire her. Uhri told me in an email that he saw Franklin as a leftist figure who taught her audience about “supporting labor in opposition to capital, preferring internationalism instead of the limited horizon of nationalism, choosing society over the individual, and standing in solidarity with the oppressed.” He continued, “her support [for] black people’s rights, hence the rights of minorities and oppressed people was the most important component of leftist thought, along with labor, society, and internationalism.”

The lokma ritual for Franklin in Karaburun was coincidentally, but serendipitously, held on the seventh day of her death, but Uhri was doing more than just carrying out a ritual for her soul: giving away lokma was a way to communicate Aretha Franklin’s message to the inhabitants of Karaburun, and make them pay attention to what Franklin advocated for in her career as a musician and as an activist. People danced to Franklin’s songs, and they got to know her and her legacy better, Uhri told me.

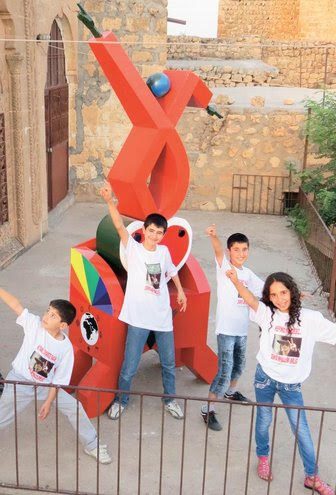

While the Turkish ritual performed in Franklin’s honor was fairly traditional all things considered, the ceremonies held for Michael Jackson in Midyat took a different, more material, turn. Under Mehmet Ali Aslan’s leadership, Midyat residents turned their commemoration up a notch by erecting a monument. The monument’s design was influenced by Jackson’s famous dance move, the moonwalk. The abstract sculpture is full of symbolism: it has a globe as a symbol of internationalism, an index finger pointing forward as a symbol of the region’s monotheist religions, multiple colors on the sides as a symbol of many “races” of humankind, and a rainbow as a symbol of living together despite differences. The monument’s designer, architect M. Hıfzı Turgut, introduced the monument’s main theme as “kıyam” (resistance) because to Aslan, Jackson symbolizes resistance to oppression. Explaining his community’s enthusiasm in celebration Jackson, Aslan emphasized, (alongside Jackson’s position as a member of their extended family,) his “universal” qualities, and how he touched people’s lives through entertainment. Embracing Jackson’s legacy, Aslan said, means embracing what Jackson stood for: universal acceptance, multiculturalism, and humanism—all qualities that are embraced by Midyat locals.

Unfortunately, nature had its own plans for Jackson’s legacy. The Midyat monument was destroyed by a storm in 2012. This prompted the villagers to repair the monument and to plant a memorial forest in the King of Pop’s name. Mehmet Ali Aslan, who continued to spearhead the Jackson commemorations, explained that the forest “would combat the natural disasters, contribute positively to the nature and environment, and keep [Jackson’s] deed pages [amel defteri] open.” Today, Jackon’s deed pages are still being inscribed: his Turkish forest is flourishing.

Although the memorial forest is officially named only after Michael Jackson, Mehmet Ali Aslan also dedicated the forest during the planting ceremony to one more black public figure: Malcom X. According to Aslan, Jackson and Malcom X were both “mazlum” (the oppressed), and by dedicating this memorial forest to them, he was spreading a message of peace to the Middle East and the world. Ahmet Uhri gave a similar explanation for why Aretha Franklin and her activism in support of black people’s struggle in the US was so important for leftists internationally.

Considered together, Aslan’s and Uhri’s public death rituals accomplish multiple things at once: they express gratitude for what these stars symbolized while they were alive, while turning their deaths into opportunities to spread their messages and legacies to those who are not familiar with them. Moreover, through these death rituals, the organizers actually induct these stars into their own families. Organizers like Aslan and Uhri are doing what a good child does for their parents — perpetuating their positive influence in their community. These rituals keep Franklin and Jackson’s deed pages open while adding more good points in their name for Judgment Day. One cannot help but wonder what Franklin and Jackson’s faces will look like on the Judgment Day when they notice among their good deed pages some solid entries in the form of Turkish lokma and trees.

***

[1] In the Sunni sect of Islam, there are four major schools of Islamic law: Hanafi, Maliki, Hanbali, and Shafi’i. Although the majority of Sunnis in Turkey follow the Hanafi school, most Sunnis in the Kurdish region follow the Shafi’I school.

***

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.