In the News: Migration, Antisemitism, Climate Change & Vampires

A roundup of recent religion writing.

Welcome to our November religion(ish) writing roundup. Maybe the thing we’ve felt most over the last couple of years (no, not that feeling, but, okay, right, yes, also that one) is that sense of, “Where do we even start?” It’s only been one month since the last collection of links and, in the time, how many breaking and breathtaking stories have crashed over the transom? It really is impossible to know where to start sometimes. But this month, we’re starting with migration, the focus of an ongoing project by our friends over at The Magnum Foundation, and the subject of some really crucial and excellent new writing.

Borderlands of the Sacred by Rachel McBridge Lindsey for The Immanent Frame

But classifying religious objects in El Sueño Americano as in some fundamental way distinct from the other objects on display in the photographs misses the bigger picture. Every confiscated object is remade through the ritual of staging and photographing as Kiefer performs the priestly role of transforming mundane objects into sacred hosts, tabernacles of dignity that migrate across the borderlands of sacred and secular. On the surface, El Sueño Americano employs a visual strategy not unlike the HHS photographs of detention facilities. Both series, for instance, frame commonplace objects to familiarize their subjects, investing those objects with the power to invoke bigger truths, be it common humanity, for Kiefer, or, in the government series, a benevolent state. But beyond what Kiefer may mean by “sacred object”—and I think he is sincere in using that language—there is a reckoning at work in El Sueño Americano that differentiates it from the government photographs. Toothpaste, combs, nail clippers, bandanas, clothing, gloves, razors, rosaries, worn surfaces of La Virgen de Guadalupe, scuffed covers of Nuevo Testamento, each refer back to the bodies of those who have sought refuge in the grand, unfulfilled American promise of human dignity and who have borne the burden of its failure.

(We also highly recommend two other ongoing series over at The Immanent Frame, “Science and the soul: New inquiries into Islamic ethics” and “Couture and the death of the real”

Nuevos Testamentos by Tom Kiefer.

Placed upon a migrants’ bandana, these New Testaments were considered non-essential personal property and discarded during the initial stages of processing.

We were very glad to see this: Columbia Law Professor Files Amicus Briefs on Religious Liberty Claims Raised in Federal Prosecutions of Activists in Arizona Who Left Water and Food In Desert For Migrants

This case raises important questions regarding the use of RFRA as a defense in a criminal prosecution,” said Professor Katherine Franke, the principal author of the brief. “As legal scholars of religious liberty it is our concern that RFRA [the Religious Freedom Restoration Act] is interpreted consistently across contexts where sincerely held religious beliefs are substantially burdened by government action. We note in the brief that the Justice Department has taken a position in this case that is much less protective of religious liberty than it has in cases where the underlying issues are more aligned with the administration’s political agenda,” continued Franke.

But devastated reading this: Caravan Walks Quietly On, U.S. Opposition a Distant Rumble by Krik Semple and Todd Heisler for The New York Times

Even from the early days of their trip, many migrants in the caravan knew Mr. Trump had cast them as an invading horde looking to game the system and steal jobs from United States citizens. But to many, his declarations have been little more than a distant rumble on the horizon, a problem for later.

Driven by a deep faith rooted in Christianity, many have clung to a belief that everything would work out in the end, that Mr. Trump’s heart would be touched and he would allow them into the United States to work.

Even Ms. Alvarado subscribed to this hopeful philosophy.

“Well, I can’t think the opposite way,” she shrugged.

Religion is everywhere in the story of immigration and of life in our city right now, as we see in this story, Debora Barrios-Vasequez Took Sanctuary in a Manhattan Church to Avoid Deportation by Laura Gottesdiener (with photographs by Cynthia Santos Briones) for The Nation

By taking refuge in the church, Barrios-Vasquez has become part of a growing number of undocumented immigrants who have sought physical sanctuary inside religious institutions across the United States, even as they know full well that the cost of safety is self-imprisonment. But if the church walls have offered Barrios-Vasqueza a fraught form of protection, it’s inside the church’s small theater—just down the hall from her temporary bedroom—that she has also found mental and emotional refuge, full of laughter, distraction, and an alternative reality that she has the unique power to create.

And this sickening one, too: Immigrant Communities Were The ‘Geographic Solution’ To Predator Priests reports Aaron Schrank for NPR

Catholic Church leaders in Los Angeles for years shuffled predator priests into non-English-speaking immigrant communities. That pattern was revealed in personnel documents released in a decades-old legal settlement between victims of child sex abuse by Catholic priests and the Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles.

Now clergy sex abuse victims throughout California are calling on the state’s attorney general to investigate clergy abuse and force church officials to release more information about their role covering it up. The goal is to discover how wide-spread the practice of hiding abusers in immigrant communities really was.

And, brutally, linking the immigration to another of the month’s tragedies, Masha Gessen explained Why the Tree of Life Shooter Was Fixated on the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society for The New Yorker

For me, Bowers’s obsession with HIAS [Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society] made a warped kind of sense. I imagine Bowers’s world view is a distorted reflection of Donald Trump’s. The President fans hatred for immigrants, trans people, and Muslims. In Bowers’s mind, HIAS with its commitment to helping all displaced people worldwide, becomes the perfect target for all hatreds. Trump’s message transforms into the idea that Washington is not doing enough, because terrorists equal refugees equal HIAS equal all Jews.

With its commitment to helping all displaced people worldwide, HIAS becomes the perfect target for all hatreds.Photograph by John Altdorfer / Reuters

While Tara Isabella Burton interviewed Talia Lavin in How anti-Semitism festers online, explained by a monitor of the darkest corners of the internet at Vox

I think that people don’t understand the degree to which anti-Semitism is both vital to and inextricable from white supremacy in the US. In the same way that the white genocide theory applies to pretty much the entirety of the extremist worldview, the world that they envision, the one that they believe they inhabit, is one in which Jews create nefarious schemes for nonwhite people to carry out as their puppets in order to support and destroy the white race.

And an On the Media published a segment, hosted by Bob Garfield, about Why the Origins of Antisemitism Matter

While, also, The Alt-Right’s Favorite Meme is 100 Years Old explained Samuel Moyn in an op-ed for The New York Times.

And while increasingly popular worries about cosmopolitan elites and economic globalization can sometimes transcend the most noxious anti-Semitism, talk of cultural Marxism is inseparable from it. The legend of cultural Marxism recycles old anti-Semitic tropes to give those who feel threatened a scapegoat.

And Ed Simon wrote beautifully about Praying for the Awful Grace of God for McSweeney’s

No portrait exists of the seventeenth-century prophetess Anna Trapnell, because she was not of the station for whom people made portraits. Poor daughters of Stepney shipwrights didn’t have paintings made; women whose parents hadn’t baptized them were not fixed in stained glass. But God, or whatever you call Her, doesn’t just visit those in whose likeness icons are made. In 1654, when Trapnell was in her twenties—the exact year of her birth being unknown—she traveled to Bridewell Palace and sat in ecstatic vigil against the increasingly tyrannical theocracy of Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell. She spent twelve days in a trance, speaking paradox and poetry, prophecy and prayer, predicting the collapse of the government so many had initially welcomed after monarchical absolutism. Attended by non-conformists, dictating to an amanuensis, Trapnell repeated prayers like “The Voice and Spirit have made a league / Against Cromwel and his men, / Never to leave its witness till / It hath broken all of them.” She was apprehended and put on trial for witchcraft, but against all our presumptions of her era she beat the charge. She was simply too popular, too brilliant, too powerful for the state to end her ministry.

It’s strange to consider the political power of prayer, especially against a state that also enshrines its efficacy. Some on the left assume that anyone who talks too much about prayer has an agenda, usually a reactionary one. After all, there are plenty of contemporary Cromwells legislating and dictating their religious beliefs. With men like this—they’re normally men—it’s easy to forget the radical, awesome, subversive power of prayer, even while those we’re resisting claim it as their own too. It’s easy to grow cynical after being perennially offered “thoughts and prayers” in the never-ending wake of American bloodletting, but what if we took prayer seriously? What if we embraced it in all its awful grace? What if we answered the Cromwells of America as a vast legion of Trapnells bursting with prophecy? Then we’d have a real revival. Then we’d have a revolution.

And yet, somehow (?), at the same time (???), Vatican releases its own ‘Pokémon Go’ app that lets you chase Jesus and it’s just as unbelievable as it sounds

Rather than chasing after Pikachu and Squirtle, the Vatican version involves collecting saints and other Biblical figures by answering philosophical questions about them. One hypothetical query on the app’s website is “Who said ‘My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?'” (Hint: it was Jesus.)

Once players “catch ’em all” using geolocation, their spiritual squad becomes an “evangelization team” that follows Jesus together. Players have to keep track of their avatars’ nutrition, hydration and “prayer count” by collecting special objects, saying prayers for the sick in hospitals and going into a church whenever they pass one.

We’d rather be on the lookout for this guy: The Return of the Vampire Kings of New York, profiled by Sam Kestenbaum for The New York Times

Two women squeezed in the stall to be fitted for fangs. “I’m a modern-day vampire who loves life,” said Christina Staib, a woman with leather boots and bat tattoos. Her friend Melanie Anderson had come for her first pair. “They give off an aura,” she said. “A spiritual vampire aura.”

Father Sebastiaan is just the man to help cultivate that aura. A 43-year-old with long hair, the fang maker once styled himself the king and spiritual guru of New York’s vibrant vampire scene in the 1990s. He hosted raucous parties, wrote books and launched product lines — jewelry, contact lenses and the fangs — with financial success. It was a good time to be a vampire in New York.

But he was toppled by critics and rivals and, ultimately, a city that outgrew its vampire moment. Fortunes rise and fall, but the fang maker’s travails are particularly unusual — and include spirit encounters in dance clubs, the disappearance of a young journalist and feuding gangs of self-professed vampires.

Or remembering when Heaven Was a Place in Harlem: The radical tableside evangelism of Father Divine by Vince Dixon (with many quotes from Judith Weisenfeld) for Eater

The Peace Mission’s banquets served as a riff on the Eucharist and Christian communion, but the group also used food as a form of evangelism. For Divine and the Peace Mission — like many religious movements before them — the stomach was the route to salvation. Amid the Great Depression, World Wars I and II, Jim Crow segregation in the South, and de facto segregation in the North, Peace Mission members ate for free and in abundance at the banquets. Peace Mission followers argued that the bounty was not merely a gesture of Divine’s generosity, but a tangible gift from the man they called God. Rejecting the mainstream Christian “heaven in the sky” belief, the Peace Mission argued that heaven was accessible here on Earth, and Divine’s bounty was the literal proof in the pudding, according to Sylvester Johnson, director of Virginia Tech’s Center for Humanities and an expert in African-American religious history. “They used the banquets as evidence that the Mission was bringing salvation,” Johnson said. “That salvation was for the here and now and not just something that you had to get after you die.”

Or listening along with Will Bostwick‘s profile of historian Robert Darden’s Black Gospel Music Restoration Project in Deep River for Oxford American

In February of 2005, Darden wrote an op-ed in the New York Times lamenting the loss of these treasures from gospel’s golden age: “It would be more than a cultural disaster to forever lose this music,” he writes. “It would be a sin.” The apparent imbalance of that remark stuck with me. By any honest standard, we sin regularly. A cultural disaster seems like a much more grievous affair. But I also had the feeling that he was onto something—that the loss of this music was a moral failing born out of a history of oppression and neglect. He explained to me that when he wrote that, he had in mind Jim Wallis’s (at the time controversial) claim that racism was America’s original sin.

The day the op-ed came out, Charles Royce, an investor from New York with no particular ties to gospel music, called Darden and asked what needed to be done to save what remained of the music. With Royce’s funding, and with the institutional support of Baylor University libraries, Darden and his colleagues started the Black Gospel Music Restoration Project. In a 2007 interview with Fresh Air’s Terry Gross, Darden said, “We see it as kind of like those seed banks up around the Arctic Circle that keep one copy of every kind of seed there is in case there’s another Dutch elm disease. I just want to make sure that every gospel song, the music that all American music comes from, is saved.”

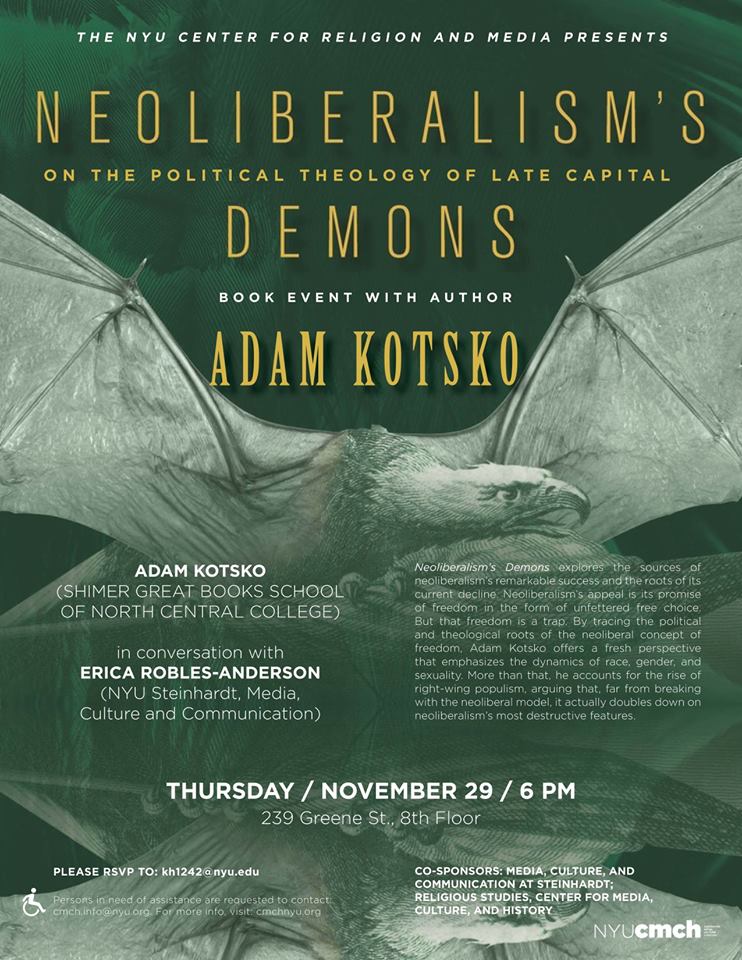

But back we should head back to the news: The Political Theology of Trump: What looks like hypocrisy is the surest possible evidence that God is in control by Adam Kotsko for n+1

The question now is how to confront this strange view of politics. In my experience, many secular liberals view the ideal intervention as something like the first episode of The West Wing, when President Bartlett meets with a group of evangelical Christian leaders and schools them in scripture, leaving them in stunned silence. But this is simply not how it works—otherwise evangelical Christians would have been open to dialogue with the Clintons and Obamas on the basis of their obvious Christian faith. Evangelicals don’t want dialogue or negotiation. They certainly don’t want to be schooled on their own scriptures and values by outsiders. In a sense they don’t want to be doing politics at all. They want to live in a world that is ruled by God, and their convoluted political theology has led them to the conclusion that this is what Trump has offered them.

For another great conversation, check out Yasmin Moll’s interview with Matthew Engelke about Thinking Like an Anthropologist for Public Books

How to Think Like an Anthropologist is a self-help book, then, only in the sense of cultivating what I believe is still best represented by one of Ruth Benedict’s arguments: that other people do things in other ways for perfectly good reasons, and that we are better people for coming to understand those ways. Not necessarily to adopt them. Not necessarily to accept them, but actually to engage with them seriously. That’s our most helpful form of self-help, I’d say.

This month, let’s end (not too apocalyptically, we hope) with some work on Climate Change. First, Ava Kofman‘s excellent profile of Bruno Latour, the Post-Truth Philosopher, Mounts a Defense of Science for The New York Times Magazine

Those who worried that Latour’s early work was opening a Pandora’s box may feel that their fears have been more than borne out. Indeed, commentators on the left and the right, possibly overstating the reach of French theory, have recently leveled blame for our current state of affairs at “postmodernists” like Latour. By showing that scientific facts are the product of all-too-human procedures, these critics charge, Latour — whether he intended to or not — gave license to a pernicious anything-goes relativism that cynical conservatives were only too happy to appropriate for their own ends. Latour himself has sometimes worried about the same thing. As early as 2004 he publicly expressed the fear that his critical “weapons,” or at least a grotesque caricature of them, were being “smuggled” to the other side, as corporate-funded climate skeptics used arguments about the constructed nature of knowledge to sow doubt around the scientific consensus on climate change.

But Latour believes that if the climate skeptics and other junk scientists have made anything clear, it’s that the traditional image of facts was never sustainable to begin with. “The way I see it, I was doing the same thing and saying the same thing,” he told me, removing his glasses. “Then the situation changed.” If anything, our current post-truth moment is less a product of Latour’s ideas than a validation of them. In the way that a person notices her body only once something goes wrong with it, we are becoming conscious of the role that Latourian networks play in producing and sustaining knowledge only now that those networks are under assault.

Bruno Latour at a theater in Strasbourg, France, in March, rehearsing for his show “Inside,” a performance lecture about climate change.CreditLuca Locatelli for The New York Times

Which reminded us of A philosopher [who] invented a word for the psychic pain of climate change

Solastalgia is a combination of three elements: “Solas” references the English word “solace,” which comes from the Latin root solarimeaning comfort in the face of distressing forces. But it is also a reference to “desolation,” which has its origins in the Latin solus and desolare, which both connote ideas of abandonment and loneliness. “Algia” comes from the Greek root -algia, which means pain, suffering, or sickness.

Solastalgia, Albrecht writes, has the added benefit of being a “ghost reference” to nostalgia, sounding similar enough to evoke the feeling of longing contained in that word. “Hence, literally, solastalgia is the pain or sickness caused by the loss or lack of solace and the sense of isolation connected to the present state of one’s home and territory,” he writes. Solastalgia, then, is a very intimate word, describing a psychic pain with very specific origins.

And, if you are in search of actual solace, the one thing consistently bringing us delight, calm, wanderlust, and so much hunger is Samin Nosrat’s Sensual, Compassionate Food Travels in “Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat” which Doreen St. Félix wrote about beautifully (even, religiously) at The New Yorker.

“Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat” is a wistful picture of a kind of ecological harmony that’s nearly extinct. A strange flavor lingered after I finished watching. It was sadness, a nostalgia for the unpolluted vistas, and their fruits, which I, idling in the antiseptic aisles of the chain market, have never known. Within our species, there are those who have profaned food sources and those who have respected them. “Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat” is an ode to the people who worship the edible in the most complete sense. It makes you wish they had won.

But, if you happen to find more solace in schadenfreude these days, we don’t blame you, and this final link is for you: Women for Trump Founder Says GOP in Danger Because Witches Put a Hex on Brett Kavanaugh.

We’ll see you in December!

***