Blessings of Business

Eden Consenstein reviews Blessings of Business: How Corporations Shaped Conservative Christianity by Darren Grem

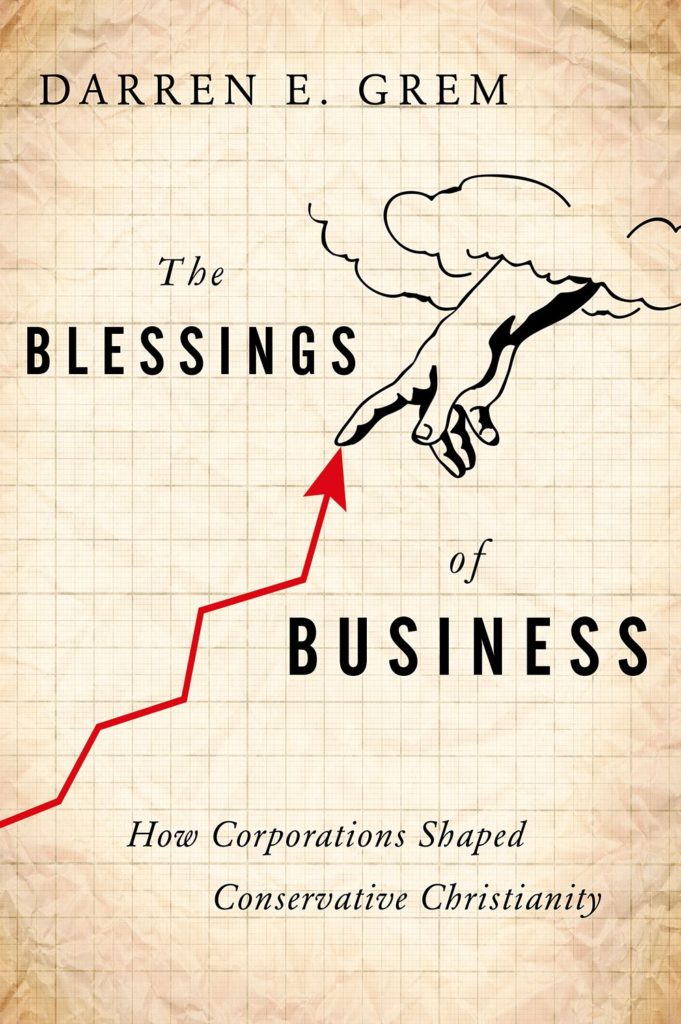

Darren Grem’s Blessings of Business: How Corporations Shaped Conservative Christianity opens with the image of celebrity preacher Billy Graham blessing a cargo ship about to set sail for Liberia on a sunny morning in July 1952. The ship, stacked with 500 copies of the New Testament and manned by “technical missionaries,” belonged to Graham’s friend and business associate, R. G. LeTourneau, then president of one of the biggest engineering and earthmoving companies in the world. Harmonizing business savvy and religious ambition, LeTourneau had arranged with the Liberian government to clear-cut land that would then be used to grow rice, bananas, and grapefruit. For the first five years profits from the crops would go toward missionary efforts. Thereafter, they would go to LeTourneau. This opening vignette quickly captures the web of strategic alliances that Grem untangles in Blessings of Business. By identifying and describing such moments of synergy between corporate actors and Evangelical aims from the 1920s to the 1990s, Grem charts how business elites sponsored Evangelical efforts, and how Evangelicals came to mobilize businesses to express their faith.

The book is organized into two chronologically ordered sections. The first, “How Businessmen Shaped Conservative Evangelicalism,” covers roughly the 1920s through 1960s, when capital supplied by both business and the state allowed conservative Evangelicals to create powerful and enduring social networks. Starting with Christian aluminum magnate Herbert J. Taylor’s leadership in local Rotary clubs, Grem explains how conservative Christian businessmen in the 1930s and ‘40s created organizations, like the Christian Businessmen’s Committee International (CBMCI), where they could share strategies for bringing faith to business without compromising the bottom-line. First activated by the tumult of Depression and later reacting to the perceived threat of New Deal-era social policies, these organizations ultimately took on an activist bent. Worried that a more liberal social order might threaten their religious autonomy and limit the productivity of their enterprises, organizations like Rotary and CBMCI crafted new political arguments that described Christianity and capitalism as mutually-dependent social goods, increasingly endangered by liberal policies at home and communism abroad.

The book is organized into two chronologically ordered sections. The first, “How Businessmen Shaped Conservative Evangelicalism,” covers roughly the 1920s through 1960s, when capital supplied by both business and the state allowed conservative Evangelicals to create powerful and enduring social networks. Starting with Christian aluminum magnate Herbert J. Taylor’s leadership in local Rotary clubs, Grem explains how conservative Christian businessmen in the 1930s and ‘40s created organizations, like the Christian Businessmen’s Committee International (CBMCI), where they could share strategies for bringing faith to business without compromising the bottom-line. First activated by the tumult of Depression and later reacting to the perceived threat of New Deal-era social policies, these organizations ultimately took on an activist bent. Worried that a more liberal social order might threaten their religious autonomy and limit the productivity of their enterprises, organizations like Rotary and CBMCI crafted new political arguments that described Christianity and capitalism as mutually-dependent social goods, increasingly endangered by liberal policies at home and communism abroad.

In Chapter 2, “Corporate Convictions: Billy Graham, Big Business and the New Evangelicalism,” Grem focuses on famed Evangelist Billy Graham, who brought the association between conservative Evangelicalism and corporate capitalism to the American mainstream. A believer in the inherent interconnectedness of Christianity and free markets, and a singular orator to-boot, Graham popularized a form of conservative Christianity born in board room. Grem describes how Evangelical businessmen ensured Graham’s national platform by furnishing his mission with slick advertising and professional market research. The first section’s final chapter returns to LeTourneau, bringing the state into the picture. Here, we learn that despite his anti-statist rhetoric, LeTourneau’s earthmoving business was buoyed by World War II-era government contracts.

Closely following LeTourneau, Taylor, and Graham, Grem illuminates the machinations of the people too-often “hidden at the top,” and provides a trenchant rejoinder to the common assumption that conservative Evangelicals exist mostly on embattled social margins. To the contrary, he confidently maps the “monied infrastructure” that came to support a vast and varied culture of conservative Evangelicalism.

In Blessings of Business’s second section “How Conservative Evangelicalism Became Big Business,” which covers the 1960s to the 1990s, Graham, Taylor and LeTourneau’s world of tightly interconnected Christian business alliances gives way to a more-diffuse constellation of businesses and characters linked through association and affinity. Where the partnerships described in the book’s first section carved-out space for Evangelical interests in the national market, the Christian entrepreneurs we meet in the second section provided Christian consumers with alternatives to a national culture that they viewed as rife with immoral excess.

In Chapter 4, “Marketplace Missions: Chick-fil-A and Evangelical Business Sector,” Grem colorfully describes how Chick-fil-A founder S. Truett Cathy brought Christianity to the food court. Drawing on notions of “Christian managerialism” (innovated by the previous chapters’ generation of Christian businessmen) Cathy’s Sunday closures and fastidiously clean-cut employees made Chick-fil-A uniquely appealing to Christian customers, and pious parents looking for their teenager’s perfect first job. A similar dynamic is on display in Grem’s engaging chapter on televangelist Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker’s Christian theme park, Heritage USA. Mimicking the idiom of Disneyland but adding a decisively Christian message, the Bakkers provided Christian vacationers with an opportunity to express their faith through their choice of destination. And nearly a century’s worth of association between business-building and conservative Christianity find their conclusion in a chapter on Zig Ziglar, the conservative Christian self-help mogul. Grem describes Ziglar’s message as “free market faith,” the belief that with perseverance and faith anyone could become a business elite. Starting with Graham and ending with Ziglar, Grem captures a shift from business-backed Evangelism, to Christian evangelizing for the promise of business.

Blessings of Business is one example of the generative “business turn” in histories of American religion. Such studies, including Kevin Kruse’s One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Created Christian America and Bethany Moreton’s To Serve God and Wal-Mart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise, have provided a thorough account of Evangelical Christianity’s productive relationship with corporate business. What sets Grem’s study apart is the range of people and enterprises covered and the density of memorable historical apercu. Bringing such a broad array of actors into the same volume draws out exciting examples of both consistency and change-over-time. For example, thinking about Ziglar’s success across media platforms alongside LeTourneau’s state-of-the-art earthmovers and Cathy’s improved chicken fryer, Grem shows that business-minded Evangelicals were consistently aided by their interest in (and access to) the newest technologies. Beginning with responses to the Depression and New Deal and ending with late-twentieth century spectacles like Heritage USA shows how early attempts to influence national culture were often more successful in creating a robust counter-culture.

Moreover, Grem is careful to point out that all of these movements were enabled by social and economic privilege. Blessings of Business is populated almost exclusively by economically mobile white men. Grem artfully shows how these men fused conservative religion with corporate power to maintain their profit margin and acquire influence. This is a story told from the top. Blessings of Business is not especially attentive to the Americans who watched Billy Graham on television in the ‘50s or frequented Heritage USA in the ‘80s. With the exception of some suggestive allusions (for example, as Grem closes the book with Ronald Reagan’s election, he notes that child poverty rose every year between 1981 and 1989) the reader is left to hypothesize about the consequences of the political, economic and religious alliances that have built-up throughout the book.

Grem and others have convincingly demonstrated that “evangelicals successfully embedded born-again Christianity in the very institutions, businesses, organizations, and political networks that make up present-day corporate capitalism,” but this entrenchment of power is less-frequently brought into conversation with the social circumstances it has precipitated. From anti-unionism in the early twentieth century to the promises of televangelists forty years later, Blessings of Business would have been even more textured with occasional discussion of the responses and fall-out Grem’s businessmen incited. This presents an exciting space for future studies. Grem’s detailed and engaging business history of Evangelicalism provides a treasure trove of potential research projects. Students of American religious history will find inspiration in the minor characters and business ventures that make cameo appearances throughout the text, and in the interaction between these powerful personalities and the varied lives they influenced.

***

Eden Consenstein is a PhD student studying religion in the Americas at Princeton University. She holds a B.A. in Religious Studies from the University of Toronto and an M.A. in Religious Studies from New York University. Eden is interested in connections between religion, information, media, business, and politics in the United States during the mid-twentieth century. Her dissertation will address these themes via the Time-Life corporation and its founder, Presbyterian media mogul Henry R. Luce.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.