The Siege at the Bridge: James Martin and the Fight Over LGBT Catholics

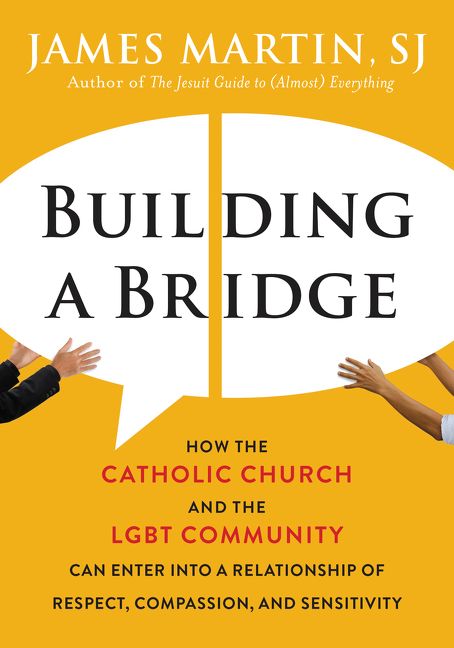

Michael Pettinger reviews Building a Bridge: How the Catholic Church and the LBGT Community Can Enter into a Relationship of Respect, Compassion, and Sensitivity by James Martin, SJ

Building a Bridge: How the Catholic Church and the LBGT Community Can Enter into a Relationship of Respect, Compassion, and Sensitivity by James Martin, SJ. Harper Collins, 2017.

James Martin knew that his book, Building a Bridge: How the Catholic Church and the LBGT Community Can Enter into a Relationship of Respect, Compassion, and Sensitivity, would trigger strong reactions. We live, he points out, in a world where maintaining civility among those who disagree seems increasingly difficult. “Not too long ago, opposing factions would often interact with one another politely and work together for the common good. Certainly there were tensions, but a kind of quiet courtesy and tacit respect prevailed. Now all one seems to find is contempt.” Martin, editor at large at America: The Jesuit Review, would like the Church to be different, for it to be “a sign of unity.” He knew that arguments were sure to surround his book, but he hoped that the participants would take to heart the values of “respect,” “compassion,” and “sensitivity,” values the Catechism of the Catholic Church demands with regard to “homosexual” persons.

Since the book’s publication, Martin has been accused of spreading confusion, ignoring “intrinsic evil,” and advocating “homosexualism.” Fantasies of him being beaten “like a rented mule” by a Dominican have been tweeted into the ether. His sexual orientation has been questioned, and he has been called “pansified” for protesting this kind of abuse. All of this has been done to him by self-identified Catholics.

That’s not to say that the Catholic response has been universally negative. The cover of the book carries positive blurbs written by two cardinals and a bishop. Since then, more prelates have come to Martin’s defense. Others have been respectful, but less friendly. Cardinal Robert Sarah, prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments wrote a carefully worded critique, singling out, among other things, the book’s failure to clearly articulate the official church teaching on same-sex acts and its silence about Catholics who are “same-sex attracted” but choose to live in chaste celibacy as the Catechism demands. Sharper criticisms were made by Thomas Tobin, bishop of Providence, who likened the book to “a bridge to nowhere.” (Bishop Tobin is not to be confused with William Tobin, cardinal archbishop of Newark, who celebrated Mass for a group of LGBT Catholics this summer).

That’s not to say that the Catholic response has been universally negative. The cover of the book carries positive blurbs written by two cardinals and a bishop. Since then, more prelates have come to Martin’s defense. Others have been respectful, but less friendly. Cardinal Robert Sarah, prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments wrote a carefully worded critique, singling out, among other things, the book’s failure to clearly articulate the official church teaching on same-sex acts and its silence about Catholics who are “same-sex attracted” but choose to live in chaste celibacy as the Catechism demands. Sharper criticisms were made by Thomas Tobin, bishop of Providence, who likened the book to “a bridge to nowhere.” (Bishop Tobin is not to be confused with William Tobin, cardinal archbishop of Newark, who celebrated Mass for a group of LGBT Catholics this summer).

Given these sorts of reactions, you might be forgiven for expecting Martin’s book to be universally praised by LGBT Catholics. That has not been the case. Jamie Manson, books editor at the National Catholic Reporter, who is lesbian, complained that, “for some Catholics, particularly longtime LGBT activists, certain sections may… read like fiction.” She noted that Martin holds a privileged position in the church, enjoying relationships with “many cardinals, archbishops, and bishops,” and that he claims that all the members of the hierarchy in his circle of acquaintance “are sincere in their desire for true pastoral outreach” to LGBT Catholics. Manson sees this as an attempt to convince LGBT Catholics that, “in their lack of access to the power center of the church, [they] are simply ignorant of what’s really going on in the hearts of these men.” Her response is a detailed list of recent episcopal activity, collective and individual, including renewed efforts to defend “traditional marriage” and “religious freedom,” the firing of church workers if they legally marry their same-sex partners, discussions of “the problem of ‘transgenderism’” at the National Catholic Bioethics Center, and moves to deny the Eucharist and Catholic funerals to people in same-sex marriages.

It’s not immediately clear what the media storm surrounding Martin’s book says about Catholics in the pews, but it does show that the online presence of Catholics is no less divided, divisive, and vitriolic, than the culture at large. If the book has not always succeeded in inspiring the kind of civil dialogue Martin envisioned, it might be because he underestimated the complexity of the contemporary Church in two important ways. Framed as a two-sided conversation between the “institutional church” and LGBT Catholics, Building a Bridge virtually ignores the role played in that dialogue by what is arguably the most prominent group of contemporary Catholics: married heterosexuals. Martin’s book scarcely mentions them, except in so far as they count among the “families, friends, and allies” of LGBT Catholics. Nor does it seem that Martin anticipated the out-sized role played by a few prominent converts in arbitrating the boundary between the Church and the non-Catholic culture. The issues that matter to these two groups – married heterosexuals and converts to Catholicism – are interrelated in unexpected ways that have a serious impact on the place of LGBT Catholics in the Church.

It would be wrong to deny that some Church leaders are genuinely concerned about the opinions and well-being of LGBT Catholics, but the truth is that the latter only make up a small portion of the total U.S. Catholic population. U.S. bishops have much more to fear from dissenting married heterosexuals. Figures released by PRRI in February 2017 showed not only that a majority of lay Catholics support the legal right of same-sex couples to marry, but that they are more likely to do so than the general population. More troubling still for the Church leadership is that young Catholics are no exception to the general rule that Millennials (71%) are more likely to support same-sex marriage than their elders. In an essay condemning Martin’s harshest critics, Bishop Robert McElroy of San Diego noted that, “When we survey the vast gulf that exists between young adults and the church in the United States, it is clear that there could be no more compelling missionary outreach for the future of Catholicism than the terrain that Father Martin has passionately and eloquently pursued over the past two decades.” It’s hard to miss the point. Whatever McElroy’s feelings about LGBT Catholics, his most urgent concern is that heterosexual lay people, by and large, no longer share the vision of human sexuality promulgated by the bishops, who risk becoming increasingly irrelevant in the future.

That most Catholic lay people support civil marriage for gay and lesbian couples does not, of course, mean they support the sacramental blessing of those marriages in church. (To be clear, the book never advocates that practice.) The rules governing marriage are a tender subject in the Church, since they often serve as a mark that distinguishes Catholics from the “World.” Any alteration in that discipline is bound to trigger negative reaction in some parts of the Catholic media. Two years ago, for example, when the Synod on the Family considered permitting some Catholics who have divorced and remarried without the annulment of their first marriage to receive Communion, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat recalled the role the divorce and marriage of Henry VIII played in the split between Rome and the English church, and warned of potential schism, possibly under the leadership of pope emeritus Benedict XVI. The more the practice of marriage among Catholics looks like secular marriage, the less real the distinction between the “Church” and the “World” seems. If offering the Eucharist to divorced and remarried Catholics inspires talk of schism, it is not hard to imagine what the blessing of same-sex marriages would do.

It’s no coincidence that Douthat is a convert from Protestantism, one who has publicly stated that Catholicism attracted him by its claims to historical continuity. It’s an old trope, one echoed by R.R. Reno, chief editor of First Things, who likened the Anglican Church, which he left for Catholicism, to a “ruin.” While neither Douthat nor Reno has personally weighed in on Martin’s book, First Things has published at least five items on Martin and his approach to LGBT issues since July, none of which can be called a ringing endorsement. Less well known perhaps is Dwight E. Longenecker, an American who was raised evangelical, ordained in the Church of England, and converted to Catholicism, saying that “the Anglican Church and I were on divergent paths.” Writing for Crux, Longenecker rejected Martin’s criticism of the term “same-sex attraction,” arguing that “Catholics believe every person is greater than their sexual inclinations” and that “it is degrading to identify a person only by their sexual urges.” He also took Martin to task for not recognizing the work of Courage and EnCourage, ministries intended to help Catholics attracted to the same sex to live a chaste celibacy. His arguments are consistent with the promotion of Rome as a bulwark against change.

For converts like Reno and Longenecker, resistance to any softening of Church attitudes regarding LGBT Catholics is part and parcel of a fight that began in the Reformation. There is, however, a certain confusion in the sense of Catholic identity they promote, suggesting as it does, on the one hand, that the “cultural Catholicism” of cradle Catholics is somehow lacking, while encouraging a kind of Catholic cultural tribalism on the other – a tribalism that defines itself, in part, as opposition to the increasing acceptance of same-sex relationships in “secular” society. Ironically, this vision of Catholicism even attracts some people who would otherwise identify as LGBT. About a month before the release of Building A Bridge, Daniel Mattson published, Why I Don’t Call Myself Gay: How I Reclaimed My Sexual Reality and Found Peace (Ignatius Press, 2017), with a forward by Robert Cardinal Sarah. The cover design seems to make a sly joke at the author’s expense. It shows a headshot, presumably of Mattson, his face hidden behind a sticky name tag, as if he even now he does not want to be recognized. The story he tells, however, is revealing. Sexually attracted to men at a young age, Mattson eventually had a relationship with a man, but now claims to find serenity in a life without genital activity, one that follows the official teaching of the church. While converts like Douthat, Reno, and Longenecker praise of the constancy of Rome in the face of contemporary decadence, Matson taps into an older, more essential concept of “conversion” – the renunciation of one’s own sins.

It’s a claim sure to find objections from many LGBT Catholics, but it would be unfair simply to dismiss the book as a maneuver in Sarah’s controversy with Martin. One does not have to capitulate to official Catholic teaching on sexuality to admit that sin, a very traditional Catholic word, has infiltrated and distorted the institutions of queer life, just as it does all human institutions. Where the church has failed LGBT Catholics is not in telling them that they are sinners – as Catholics, they are already inclined to believe that – but in treating their sins as essentially different from those of heterosexuals. Martin cites as a positive thing the statement in the Catechism that “homosexual persons” should be protected from “unjust discrimination,” but overlooks the obvious implication of that claim, namely, that some discrimination is “just.” Many LGBT Catholics refuse to live with this double standard. According to Mark M. Gray of the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA), LGBT respondents “raised Catholic” are significantly less likely to call themselves Catholic as adults than their heterosexual counterparts. Not surprisingly, those who do stay are less likely to attend Mass frequently. When trying to explain retention data for the population at large, Gray often turns to a “life-cycle” theory in which late adolescence and college bring about the disruption of “childhood pattern(s)of affiliation and worship.” Religious practice often picks up again when individuals marry, start families, and approach the end of life in old age. Needless to say, marriage, the raising of families, and end of life are precisely the moments when LGBT former-Catholics are most likely to run into official resistance from the church.

An honest refusal to discriminate would force the Church to articulate an ethic for all sexualities, rather than the present incoherent mix of natural law (understood strictly as procreation ethic) and romanticized gender complementarity that is belied at every turn. Martin’s attempt to focus on LGBT Catholics is a refreshing departure from the norm among clerical authors, and has the potential to move the conversation in that direction, (though saying this might encourage more hatred and anger from those who see no need for change). This potential is most manifest in the third section of the book, a series of scriptural meditations in the Ignatian tradition, intended to guide LGBT Catholics and their family, friends, and allies in prayer. At the end of the first meditation, Martin asks LGBT Catholics, “When you think of your own sexual orientation, what word do you use? Why? Can you speak to God about this in prayer?” For many Catholics, naming one’s sexuality before God might be a new and powerful idea. But so long as the same questions are not put to Catholics who are not LGBT, their LGBT siblings will remain a shuttlecock in the tense entente between celibate clergy, married heterosexuals, and the “World.”

***

Michael Pettinger is a scholar and writer, working in patristics, the history of Catholicism, and issues of sexuality. Along with Kathy T. Talvacchia and Mark Larrimore, he was co-editor of Queer Christianities. He has taught at the New School in New York, and John Cabot University in Rome. He currently lives in Brooklyn.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.