“After the apocalypse, she missed her dog”

By Elizabeth A. Castelli Reading Lucy Corin’s One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses

“After the Apocalypse, she missed her dog”

Reading Lucy Corin’s One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses

By Elizabeth A. Castelli

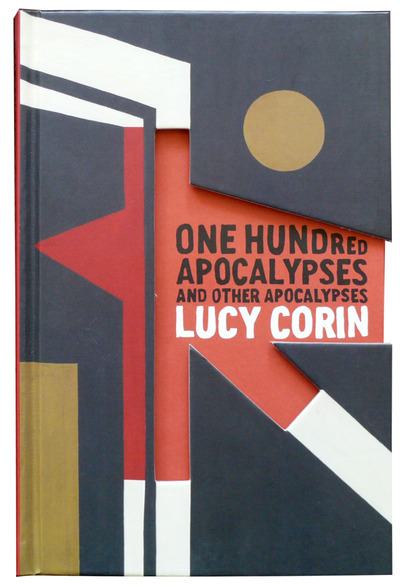

One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses

Lucy Corin (McSweeneys August 27, 2013)

A friend of mine was driving along a northbound highway from Austin to Waco a couple of weeks ago and snapped a photograph of a roadside billboard announcing a website—www.august2nd2027.com. If you visit this site, you’ll feel (as one often does when visiting websites that broadcast end-time prophecies) as though you have been transported back in time to, say, the mid-1990s when most webpages were hosted by Geocities and displayed an earnest and makeshift aesthetic favoring black backgrounds and flashing rainbow-colored fonts. There’s something so familiar about these sure-to-fail predictions—their combination of urgency and credulity and intrigue as they promote biblical interpretation via secret decoder ring.

But, of course, apocalyptic and dystopian visions are not limited to roadside pronouncements along rural highways in red states. They are rather the coin of the realm in contemporary US culture, the shadowy underside of our gilded age, part cautionary tale, part revenge fantasy. My favorite bookstore in downtown New York City, for example, currently devotes its special display table in back and one of its front windows to a celebration of “dystopian fiction,” displaying over two dozen titles from Margaret Atwood and Philip K. Dick and Samuel Delany to Cormac McCarthy and Tatyana Tolstaya and Franz Kafka, among myriad others. Meanwhile, last summer’s offerings from Hollywood included a motley collection of post-apocalyptic dystopias, zombie apocalypses, sit-com style confections about groups of friends awaiting The End, a wide array of fantasies of finality. I leave it to the culture’s psychoanalysts to diagnose the root causes of these fixations and fascinations.

This is the cultural moment into which an amazing new collection of stories intervenes: Lucy Corin’s lovely new book, One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses, published in August by McSweeney’s. Corin is already an established writer with a novel (Everyday Psychokillers: A History for Girls) and a short-story collection (The Entire Predicament) to her credit. If these earlier works fit more conventionally into recognizable genres, One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses defies easy classification. It is a compilation of three short stories (the “Other Apocalypses”) and 100 short-short stories, some of them no more than two sentences long, arranged into four sections. The stories can stand on their own as elegant and evocative snapshots, but they connect up with one another thematically through echoes and repetitions of images and formulations. Biblical apocalypses tend to offer up tours of heaven and hell; Corin’s apocalypses offer us tours of the everyday world, suburbia, urban environments, and wilderness—ordinary and familiar, but just slightly off-beat.

First off, just to get it out of the way, let me say this: Lucy Corin is a genius.

Okay then. Let’s start this discussion of the end at the beginning, with an etymology: the English word “apocalypse” derives from the Greek verb apocalyptō, a root that means “to uncover, to display, to reveal”—hence, “apocalypse” is sometimes rendered “revelation” in English. As the word has transmogrified into its contemporary usages, it has come to be synonymous with cataclysm, violence and destruction on a global scale, fire and brimstone, the End of Everything. Suppressed by such emphases is the other side of apocalypse: utopian dreams, “a new heaven and new earth” as the biblical apocalypse puts it, the fantasy of the slate wiped clean. In Corin’s apocalypses, this fantasy of freshness bubbles up repeatedly—apocalypse may promise some sort of ending that is a source of both lamentation and longing, yet pulsating under its surface are the prospect and the possibility of something new.

Corin uses the language of “apocalypse” most frequently as a temporally specific event, a happening that divides time into “before” and “after.” “After the apocalypse” signals a narratively significant temporality: “After the apocalypse, she missed her dog” – “After the apocalypse I was wandering around thinking about real magic” – “After the apocalypse, a brother of mine said: ‘Do you remember if you were nervous with all those poison spiders radiating from the jar?’” – “After the apocalypse we didn’t even talk about all the crap we’d read about it before or seen in movies. Like we were embarrassed of our whole species’ imagination” – “After the apocalypse, I see concrete” – “Postapocalypse, we were all still racist and clamoring for scraps of gold” – “One thing about after the apocalypse is you can’t get dirt on you” – “After the apocalypse she was dead anyway, but her work remained.” In each example, the cosmic cataclysm ushers in something small, particular, personal, quotidian; you are set reeling by the shift in perspective, the disorienting turn from the macro to the micro, the narrative turn itself an experience of the disruptions and disorientations of apocalypse, but also the surprising revelation that there is something “after” apocalypse – a remnant of ordinariness, a resituating of the self and the social, in spite.

Sometimes, Corin’s apocalypses focus on the utopian promise of apocalypse’s aftermath, as in the first of the one hundred apocalypses contained in the collection, a story called “Fresh.” The narrator, whose particular characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, social circumstance, etc.) remain undisclosed, confesses a longing for apocalypse: “To tell you the truth, I kept asking for it. I was looking for the apocalypse. I was tired of the way things were going. I was looking forward to fresh everything.” This story, coming first in the long series of gemlike short narratives, sets up a certain expectation—an expectation dashed three-quarters of the way through in a startling story entitled, “Bathing,” which concludes with this stark observation: “The whole point of the apocalypse was to feel clean. What a load.” In between, the intimate, embodied experience of orgasm performs metonymically as “the most productive moment of the day, because, apocalyptically, it has wiped the slate clean, and no one will ever know about it” (“Nice Day”). Taken together, these three moments capture Corin’s perspective: quotidian, embodied, a little claustrophobic, life (apocalyptically speaking, of course) as a balancing act, perching on the edge of hope and bracing for disappointment, both at the same time.

Elsewhere amidst these stories, apocalypse is not an event but the name for animated creatures or for miniature objects arrayed in a careful order and glistening with a shiny newness: “We were coming out of the movies into some real-life darkness when we heard his coat open. Rows and rows of apocalypses shone along the satin lining….the edges of the apocalypses winking in and out of view.” (Three Sisters: Blond, Brunette, Red-Head”) Or this: “He led her to a long white table, so clean, so cold, so bare, but for the apocalypses laid out in grid formation, uncountable, bouncing like icons waiting for updating, little puff of smoke in the grid, little lightning bolt, little funnel cloud, tiny tsunami, dancing flame, miscroscopic viruses magnified to match the rest, matchstick aliens, monsters like the figures on coins, anything you ever wanted. He said choose. She let several of the apocalypses run up her sleeve, down her pants, and enter her body while he wasn’t looking. She let them look out of her eyes.” (“Rate this Apocalypse”) Or this: “Stars fell in unison, and in a mossy grove on the hill, the Apocalyptasaurus was having the last sex on earth….and soon the cries of leftover apocalypses were all that remained.” (“What It Was Like”)

Ironically, this collection of stories about apocalypses doesn’t follow an eschatological structure: we are not in the framework of biblical apocalypse, which organizes history linearly and suspends events on a scaffolding of cause-and-effect, judgment-and-execution. Instead, the structure is elliptical, themes threaded through the short narratives—love, ruins, grief/lamentation/regret, memory/forgetfulness, ghosts/haunting, freshness and pollution, raggedy remnants, vision/dreams/perspective, embodiment—images looping forward and back. Yet, like a conventional apocalypse, the text inspires an almost obsessive interpretive desire: though the 100 apocalypses are independent of one another, they give the impression of a coherent pattern just out-of-reach with the promise of clarity and illumination if one can just find the key to unravel the images, the hidden patterns, the veiled secret meaning of revelation itself. They make you want to make sense of them, imprinting your experience as a reader with the coercive quality of apocalyptic.

Corin’s apocalypses insist upon the persistence of narrative, even in the wake of cataclysm. In this, they might be fruitfully juxtaposed to Anne Washburn’s play, “Mr. Burns: A post-electric play,” currently playing to sold-out houses at Playwrights Horizons in New York. On one level, a post-apocalyptic comedy, but at another level, something far more profound, “Mr. Burns” tells the story of a small group of survivors who reconstitute their frayed sociality through storytelling—in this case, trying to reconstruct from memory the “Cape Fear” episode of “The Simpsons.” As the play unfolds, time passes, and eventually the audience realizes that future generations have managed to canonize “The Simpsons” and to create out of the absurd remnants of our contemporary culture a solemn tradition. Corin’s stories strike me as having this same sort of scriptural potentiality—evocative, funny, warm, episodic, ironic, even glib at points. But stories that contain these little gems of sparkling wit and insight, apocalyptic in the sense of revelatory rather than explosive and meaning-ending.

Corin’s vision is unsentimental, sharp-edged, but yet not unkind. She knows that the world can come to an end in a fiery cosmic cataclysm—as we have all been trained by scripture and Hollywood and life in the shadow of weapons of mass destruction to understand—but also in the failure of relationship, in the last piece of cake at a dinner party, in the routine collapse of meaning that occurs when our precarious hold on the sense of things unexpectedly goes slack. Corin’s stories are set at human scale, unafraid to lay a probing hand directly upon a tender wound, comic and tragic at once, as any good apocalypse must be.

What would a secular apocalypse look like, or a religious apocalypse without God or divine judgment, without heaven or hell, but with the persistent if impossible utopian promise embedded within the apocalyptic sensibility? Lucy Corin’s stories offer a vision of just that sort of apocalypse—one that preserves the quotidian, the detailed, the narrative, and the humor that serves as a remnant and a bulwark against annihilation.

Elizabeth A. Castelli is the Ann Whitney Olin Professor of Religion at Barnard College. A specialist in biblical studies and early Christianity, she is also interested in the “afterlives” of biblical texts in contemporary culture. Her translation of Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini’s never-produced script, Saint Paul, is forthcoming from Verso Books. She is currently at work on a collection of essays on the theme of confession.